Hope for patients with a severe rare disease

By combining the results of multiple molecular analyses, scientists can better diagnose the hereditary disease methylmalonaciduria

New research offers potential benefits for those affected by the hereditary metabolic disease methylmalonic aciduria. By combining the results of multiple molecular analyses, scientists can better diagnose this rare and severe disease. In the future, an improved understanding of the disease might also improve treatment options.

In methylmalonic aciduria, a specific metabolite accumulates in the body. This often leads to patients requiring intensive medical care (symbol image).

Valérie Jaquet, Universitäts-Kinderspital Zürich

Methylmalonic aciduria (MMA) is a metabolic disorder that affects approximately one in 90,000 newborns; both parents must carry a genetic predisposition to the disease. This means the disease is rare. The consequences are also severe: an enzyme these young patients need for energy metabolism is left defective. As a result, a specific metabolite, which is usually broken down to create energy, instead accumulates in the body doing damage. MMA is considered incurable. While doctors can offer a certain degree of help, patients may experience delayed growth, kidney failure, and severe neurological impairment. Affected children and adolescents often use wheelchairs and do not always survive to reach adulthood.

Network brings success

The University Children’s Hospital Zurich is one of the leading global centers for diagnosing and treating this disease. Patient samples from all over the world are sent to Zurich for diagnosis. In a large interdisciplinary project, scientist from various Swiss research institutions studied 210 biopsies in detail. They examined not only all of the genes (DNA) in the patient’s cells but also the RNA transcripts of these genes and many of the proteins.

This is the first time that MMA has been studied using a multi-omics approach (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics). The work was initiated and funded by the ETH domain strategic focus area Personalized Health and Related Technologies (PHRT) and involved researchers from the University Children’s Hospital Zurich, ETH Zurich, EPFL, the University of Zurich, and the Health 2030 Genome Center in Geneva. The molecular analysis was carried out at PHRT’s Swiss Multi-Omics Center (SMOC) in Zurich.

Increased diagnosis accuracy

Until now, physicians have relied mainly on DNA sequencing for genetic diagnosis of MMA. However, this approach has led to repeated instances of the correct diagnosis being overlooked, reports Sean Froese, research group leader at the University Children’s Hospital Zurich and co-senior author of the study. Previous efforts have reported that only one-third to one-half of all cases can be correctly diagnosed in this way. “The reason is that everyone, even healthy individuals, has many naturally occurring genetic mutations that have no apparent impact on human health, so it’s tough to find the one or two that actually cause disease,” says Bernd Wollscheid, professor at the Department of Health Sciences and Technology at ETH Zurich, head of the Executive Committee of PHRT and co-author of the study.

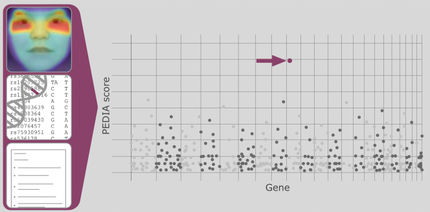

By opting to expand significantly their molecular investigation, the researchers considered not only the disease’s genetic cause but also its consequences in terms of RNA, proteins, and protein function. This enabled the consortium, as part of this study, to develop a diagnostic strategy that correctly diagnosed 84 percent of the patients examined. “Moving forward, our new method will drastically increase the chances for patients to receive a correct diagnosis,” says Patrick Forny, senior physician at the University Children’s Hospital Zurich and co-lead author of the study. “This will allow the provision of the correct treatment at a much earlier stage.”

New approach to therapy

The multi-omics data also showed that MMA patients use an alternative energy source to help deal with the fact that a vital enzyme is defective. However, in patients, this alternative energy source usually is not able to sufficiently compensate for energy production lost. In in vitro experiments with patient cells, the researchers succeeded in boosting energy production to near-normal levels by supplying such an alternative energy source.

Future investigations will show if such an approach will have the same effect in animal models and can result in a feasible therapy for patients. In addition, the researchers launched a new national interdisciplinary and interinstitutional project called SwissPedHealth, co-funded by PHRT and the Swiss Personalized Health Network (SPHN), to increase the diagnostic effectiveness further and to extend the multi-omics approach to other genetic diseases.

Original publication

Forny P, Bonilla X, Lamparter D, Shao W, Plessl T, Frei C, Bingisser A, Goetze S, van Drogen A, Harshman K, Pedrioli PGA, Howald C, Poms M, Traversi F, Buerer C, Cherkaoui S, Morscher RJ, Simmons L, Forny M, Ioannis Xenarios, Aebersold R, Zamboni N, Rätsch G, Dermitzakis E, Wollscheid B, Matthias R. Baumgartner MR, Froese DS: Integrated multi-omics reveals anaplerotic rewiring in methylmalonyl-CoA mutase deficiency. Nature Metabolism, 26. Januar 2023

Other news from the department science

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic world Diagnostics

Diagnostics is at the heart of modern medicine and forms a crucial interface between research and patient care in the biotech and pharmaceutical industries. It not only enables early detection and monitoring of disease, but also plays a central role in individualized medicine by enabling targeted therapies based on an individual's genetic and molecular signature.

Topic world Diagnostics

Diagnostics is at the heart of modern medicine and forms a crucial interface between research and patient care in the biotech and pharmaceutical industries. It not only enables early detection and monitoring of disease, but also plays a central role in individualized medicine by enabling targeted therapies based on an individual's genetic and molecular signature.