"Dormant" magnetosome genes in non-magnetic bacteria discovered

Magnetic bacteria can align their movement with the Earth's magnetic field thanks to chains of magnetic nanoparticles inside their cells. The blueprints for making and linking these magnetosomes are stored in the bacteria's genes. An international research team led by Professors Dr. Dirk Schüler and Dr. René Uebe at the University of Bayreuth has now discovered a cluster of such genes in non-magnetic bacteria for the first time. These genes are inactive but functional and probably entered the bacteria through horizontal gene transfer. The research findings were presented in the ISME Journal.

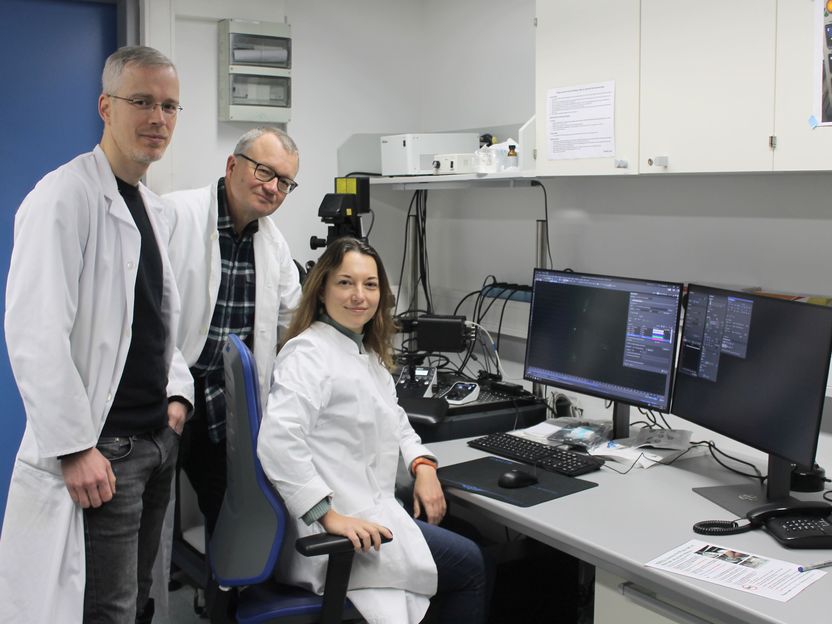

Prof. Dr. René Uebe, Prof. Dr. Dirk Schüler, and Dr. Marina Dziuba (from left) in a Bayreuth Microbiology laboratory.

UBT / Chr. Wißler

Gene transfer from one organism to another is referred to as "horizontal" when it is not "vertical" inheritance as part of a propagation process. In the realm of bacteria, horizontal transmission of genetic information is an important source of modification of existing species or emergence of new ones. The numerous genes that control the ability to synthesize magnetosomes can also be naturally transmitted horizontally to other bacteria. So far, however, these genes have only been found in bacteria that already produce magnetosomes as a result of a previous successful gene transfer. But now, the Bayreuth microbiologists and their research partners in Hungary and France have for the first time discovered a cluster of such genes in the genome of a non-magnetic bacterium. It is Rhodovastum atsumiense, which is classified as a photosynthetic bacteria because it can use the energy of sunlight for its metabolism. The magnetosome genes discovered in this bacterial species are inactive: the cells could not be induced to form magnetosomes in the laboratory, even under a variety of different culture conditions. So far, no photosynthetic bacteria are known that are naturally magnetic, although the Prof. Dr. Schüler’s team has previously succeeded in “magnetizing” such bacteria through artificial gene transfer.

"To our knowledge, this is the first detection of a complete set of 'silent' genes in a non-magnetic bacterium. This is likely an evolutionary early stage after the acquisition of the genes from another, yet unknown bacterium. Further genome analyses revealed that the transferred gene cluster most likely originated from a magnetic bacterium belonging to class Alphaproteobacteria. Future studies will show whether these genes can be activated in the natural environment of the bacteria. In any case, no activation takes place under laboratory conditions, as our results clearly show. Therefore, the presence of magnetosome genes alone does not indicate that magnetosome biosynthesis actually occurs. Caution is therefore advised when interpreting corresponding genomic data found in public databases," says Prof. Dr. Dirk Schüler, who holds the Chair of Microbiology at the University of Bayreuth.

The researchers also addressed the question of why the host bacterium Rhodovastum atsumiense did not eliminate the magnetosome genes, even though it did not derive any selection advantage from them during evolution. "The best way we can explain this, based on our genome analyses, is this: Gene transfer probably occurred at a more recent stage of evolution. Rapid elimination was not necessary because the magnetosome genes have no damaging effect on the host bacterium," explains the first author Dr. Marina Dziuba, a long-time research associate in the University of Bayreuth’s Microbiology research group.

The new research findings follow a study published two years ago. Here, the Bayreuth microbiologists succeeded in introducing the complete set of magnetosome genes from the magnetic bacterium Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense, which has long been established as a model organism in research, into the genome of a non-magnetic bacterium. Shortly thereafter, these host bacteria began biosynthesizing magnetosomes. They were apparently able to express the acquired foreign genes.