Do human embryos and cancer share the same starting fuse?

Gene activity immediately after fertilisation is used to infer how an embryo forms. Scientists now ask if cancer begins the same way

At the moment of fertilisation, the genes in the fertilising sperm and egg are switched off. For a new embryo to develop, they must be switched on – but how?

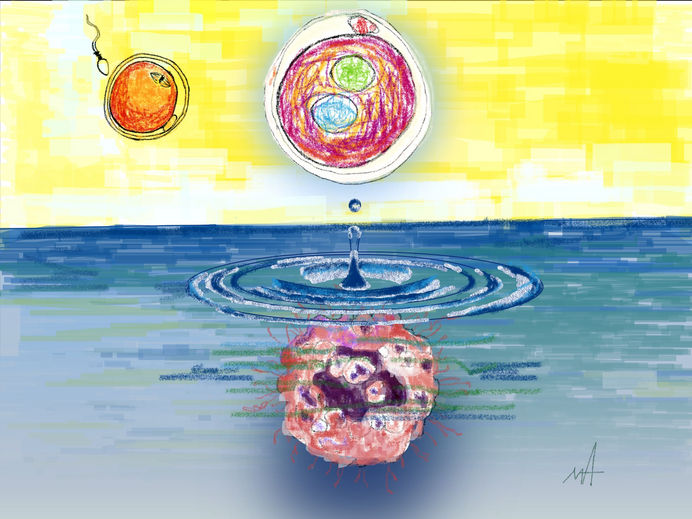

Illustration of the initiation of embryonic life immediately after fertilisation. Does the switch that begins embryo formation also initiate cancer?

Dr Maki Asami/University of Bath

The answer is unknown, which seems remarkable for such a fundamental event at the beginning of embryonic life, and for decades, it was thought that genes in human embryos were silent for several days after fertilisation. Recent findings, however, show they are switched on almost immediately.

Now that this is recognised, scientists have produced perhaps the first model of how the switch works to initiate embryonic development.

The model has been developed by Professor Tony Perry from the Department of Life Sciences at the University of Bath in the UK with colleagues Dr Maki Asami, also at Bath, and Dr Brian Lam and Professor Giles Yeo at the University of Cambridge. Their work is published in Trends in Cell Biology.

The model suggests that the myriad events that accompany fertilisation act synergistically to switch on embryo gene expression. To emphasise that the switch occurs at the start of development, the piece borrows from Under Milk Wood, by Dylan Thomas: "To begin at the beginning".

Professor Perry and colleagues have extended the model to predict something quite startling: that the switch that begins embryo formation may also initiate cancer.

The start of cancer and embryonic life

Often, by the time cancer is diagnosed, the disease is already advanced and in some cases, time is running out. We know little about how many cancers begin. It may be like lighting the blue touch paper of a firework, which is long gone when by the time see the sparkling array of colours. How can we discover the nature of this fuse, so that as soon as it is lit, we can detect it and put it out before cancer develops?

This is where a better understanding of the beginning of embryonic life fits in. The genes in an embryo need a switch to get going after fertilisation, like the touch paper in cancer.

Professor Perry and his team have previously found that the switch in embryos involves genes, called oncogenes, that play key roles in cancer.

There are many processes and players involved in embryo development whose roles we do not yet understand. For example, we don't know how the starter switch is activated.

"The switch that activates embryo gene expression is probably linked to changes in the way the embryonic genome is packaged, called epigenetic changes, but we don't know what these changes are or how they are controlled,” said Professor Perry. How can this incomplete idea about embryos be used to understand cancer?

Using embryos to understand the origins of cancer

The process of fertilisation is predictable, and the formation of a new embryo (for example, a mouse embryo) can be studied at all stages in a dish. This is not the case for cancer, whose origins cannot yet be studied in the controlled environment of a laboratory. Studying embryos allows us to identify the embryonic switch and reveal how it is activated. This will show us where to look to illuminate the origin of cancer: the lighting of the blue touch paper.

"This approach is promising given that we currently have no way of studying the initiating events of cancer,” said Professor Perry.

"In molecular terms, we don't even know what the blue touch paper looks like. Understanding the switch that starts a new embryo provides an experimental platform to reveal how the fuse is lit in cancer."

The idea is at an early stage, but it starts with a model of how healthy embryos are naturally formed: to begin at the beginning. If correct, the model will open a new and exploitable window onto the processes that initiate cancer long before clinical disease is diagnosed.

In due course, this promises to reveal new diagnostic markers that can be used to anticipate and prevent cancer.