Coronavirus formation is successfully modeled

UC Riverside study could inform the design of effective drugs to fight SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses

A physicist at the University of California, Riverside, and her former graduate student have successfully modeled the formation of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that spreads Covid-19, for the first time.

Symbolic image

Computer generated picture

In a paper published in Viruses, a journal, Roya Zandi, a professor of physics and astronomy at UCR, and Siyu Li, a postdoctoral researcher at Songshan Lake Materials Laboratory in China, offer an overall understanding of the assembly and formation of SARS-CoV-2 from its constituent components.

“Understanding viral assembly has always been a key step leading to therapeutic strategies,” Zandi said. “Numerous experiments and simulations of viruses such as HIV and hepatitis B virus have had a remarkable impact on elucidating their assembly and providing means to combat them. Even the simplest questions regarding the formation of SARS-CoV-2 remain unanswered.”

Zandi explained that a critical step in the life cycle of any virus is the packaging of its genome into new virions or virus particles. This is an especially challenging task for coronaviruses, like SARS-CoV-2, with their very large RNA genomes. Indeed, coronaviruses have the largest genome known for a virus that uses RNA as its genetic material.

SARS-CoV-2 has four structural proteins: Envelope (E), Membrane (M), Nucleocapsid (N), and Spike (S). The structural proteins M, E, and N are essential for the assembly and formation of the viral envelope —the outermost layer of the virus that protects the virus and helps facilitate entry into host cells. This process occurs at the membrane of the Endoplasmic Reticulum Golgi Intermediate Compartment, or ERGIC, a complex membrane system that provides the coronavirus its lipid envelope. The assembly of coronaviruses is unique compared to many other viruses as this process occurs at the ERGIC membrane.

Most computational studies to date use coarse-grained models where only details relevant at large length scales are used to mimic viral components. Over the years, the coarse-grained models have explained several virus assembly processes leading to important discoveries.

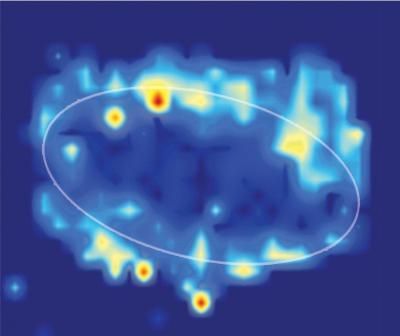

“In this paper, using coarse-grained models, we have been able to successfully model the formation of SARS-CoV-2: the N proteins condense the RNA to form the compact RNP complex, which interacts with the M proteins that are embedded in the lipid membrane,” Zandi said.

She added that “budding,” which is when a part of the membrane starts to curve up, completes the virus formation. The model Zandi and Li developed allowed them to explore mechanisms of protein oligomerization, RNA condensation by structural proteins, and cellular membrane-protein interactions. It also allowed them to predict the factors that control virus assembly.

“Our work reveals key ingredients and components contributing to the packaging of the long genome of SARS-CoV-2,” Li said. “The experimental studies regarding the specific role of each of the several structural proteins involved in the formation of viral particles are soaring but many details remain unclear.”

According to Zandi, the insight presented in the research paper and the comparison of the findings with those observed experimentally could provide some of these details and inform the design of effective antiviral drugs to arrest coronaviruses in the assembly stage.

“The physical aspects of coronavirus assembly explored within our model are of interest not just to physical scientists beginning to apply physics-based methods to the study of enveloped viruses, but also to virologists attempting to locate the key protein interactions in virus assembly and budding,” she said. “We now have a better understanding of what interactions are important for the packaging of the genome and the formation of the virus. This is the first time we have been able to fine-tune the interaction between the genome and proteins and obtain the genome condensation and the assembly simultaneously.”