Covid-19: an interferon would help children avoid severe forms

Work conducted on reconstituted respiratory mucosa in the laboratory has made it possible to study the dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adults, as well as the associated immune responses. A difference in the rate of release of a mediator of antiviral innate immunity, interferon III, could explain the lower severity of Covid-19 in younger children.

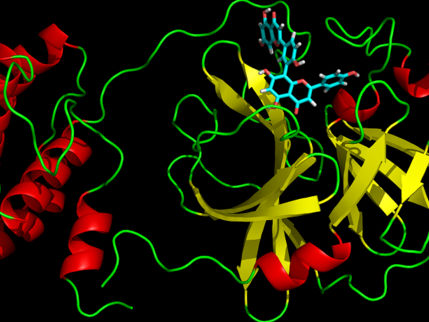

Computer generated picture

From the beginning of the pandemic, it appeared that Covid-19 was more severe in adults than in children, without any obvious explanation. So three teams of researchers came together at the first containment to address this issue. "SARS-CoV-2 infections begin in the upper airways (nose, throat, etc.). Severe forms occur after the virus has spread to the lower airways (lungs)," explains Harald Wodrich, one of the scientists involved in this work. We therefore assumed that distinct phenomena occur early in adults and in children." By bringing together their expertise in virology, imaging and pulmonology, these scientists were able to identify several pediatric peculiarities.

To study the dynamics of infection and immune response from the first days after contact with the virus, the researchers used samples of respiratory epithelium (the mucous membranes that cover the surface of the airways) taken from adults and children. They used these samples to reconstitute functional epithelia, placed in supports that mimic physiological conditions, at the interface of a culture medium (liquid) and outside air. These epithelia were then infected with SARS-CoV-2.

"In adults, we observed faster cell infection kinetics than in children. More importantly, we noted that after 3 to 4 days, cells lining the outer surface of the epithelium (epithelial cells) fuse with deeper cells (basal cells) to form large clusters that contain many copies of the virus. These clusters, called "syncytia", are able to detach from the epithelium. They can then migrate into the lower airways. Their presence has been described in the lungs of patients who died of Covid-19. This compact release of the virus could therefore contribute to the severity of the disease," explains the researcher.

A key role for interferon III

At the same time, the scientists observed that some epithelia obtained from samples taken from children are more resistant to infection, with an attenuated inflammatory response and a more rapid secretion of interferon III (IFN-III) than in adults. Syncytia formation also appeared to be less frequent, probably due to the slower time to infection. To better understand the role of IFN-III in the response to infection, the researchers conducted another series of experiments: "We found that delivering this interferon to an adult epithelium reduces viral replication and that, conversely, deleting the gene encoding IFN-III promotes viral progression and syncytia formation. Taken together, these observations could explain age-related differences in susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection, even though some adults have a response close to that of children and vice versa.

"Our approach was original because the combination of microscopy and molecular biology allowed us to visualize the differences in the spread of the infection according to the origin of the epithelia (children or adults), and to correlate these observations with the inflammatory response and viral kinetics", underlines Harald Wodrich.

The researcher wants to continue this work to find out if these phenomena are specific to SARS-CoV-2 infection or if they are found with other respiratory viruses. With his laboratory and his partners, he is currently conducting the same tests using adenoviruses and rhinoviruses, viruses responsible for generally benign respiratory infections (colds, rhinopharyngitis, etc.). "The fact that each of the epithelia we use comes from a single patient (adult or child), unlike most commercially available epithelia, will allow us to know whether differences in response are determined by the nature of the viruses or by the characteristics of the 'epithelium donor,' such as age."

As for the fight against Covid-19, these results already offer a better understanding of the phenomena behind the disease's severity. They could help clinicians optimize treatments developed to fight severe forms.

Note: This article has been translated using a computer system without human intervention. LUMITOS offers these automatic translations to present a wider range of current news. Since this article has been translated with automatic translation, it is possible that it contains errors in vocabulary, syntax or grammar. The original article in French can be found here.