Making it easier to differentiate mirror-image molecules

Researchers have shown that mirror-image substances – so-called enantiomers – can be better distinguished using helical X-ray light

Using a new method, scientists are better able to distinguish between mirror-image substances. This is important amongst others in drug development, because the two variants can cause completely different effects in the human body. Researchers from Paul Scherrer Institute PSI, EPF Lausanne (EPFL), and the University of Geneva describe the new method in the scientific journal Nature Photonics.

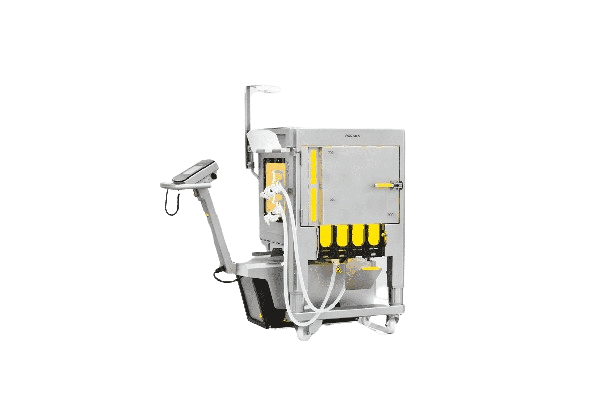

At the Swiss Light Source SLS at PSI, researchers have successfully shown that enantiomers can be distinguished from one another using helical X-ray light. Enantiomers are molecules that are mirror images of each other. Separating such molecules is relevant in biochemistry and toxicology, as well as in drug development.

Paul Scherrer Institut/Benedikt Rösner

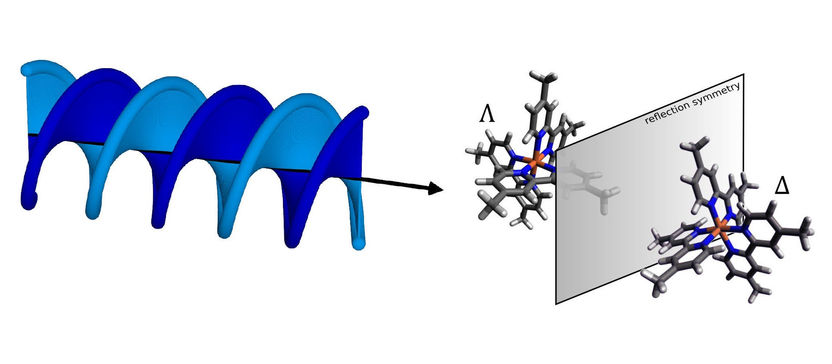

Some molecules exist in two forms that are structurally identical but are mirror images of each other – like our right and left hands. These are referred to as chiral molecules. Their two mirror-image forms are called enantiomers. Chirality is especially relevant in biological molecules, since it can cause different effects in the body. Thus it is essential in biochemistry and toxicology, as well as in drug development, to separate enantiomers from each other so that, for example, only the desired variant gets into a drug. Now researchers from PSI, EPFL, and the University of Geneva have jointly developed a new method that enables enantiomers to be better distinguished, and thus better separated, from each other: helical dichroism in the X-ray domain.

The currently established method for distinguishing between enantiomers is called circular dichroism (CD). In this approach, light with a particular property – what is known as circular polarisation – is sent through the sample. This light is absorbed to a different extent by the enantiomers. CD is widely used in analytical chemistry, in biochemical research, and in the pharmaceutical and food industries. In CD, however, the signals are very weak: The light absorption of two enantiomers differs by just under 0.1 percent. There are various strategies for amplifying the signals, yet these are only suitable if the sample is available in the gas phase. Most studies in chemistry and biochemistry, however, are carried out in liquid solutions, mainly in water.

In contrast, the new method exploits so-called helical dichroism, or HD for short. The effect underlying this phenomenon is found in the shape of the light rather than its polarisation: The wavefront is curved into a helical shape.

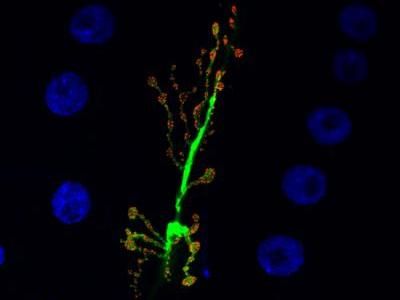

At the Swiss Light Source SLS at PSI, the researchers were able for the first time to show successfully that enantiomers could also be distinguished from each other using helical X-ray light. At the cSAXS beamline of SLS, they demonstrated this on a sample of the chiral metal complex iron-tris-bipyridine in powdered form, which the University of Geneva researchers had made available. The signal they obtained was several orders of magnitude stronger than what can be achieved with CD. HD can also be used in liquid solutions and thus fulfils an ideal prerequisite for applications in chemical analysis.

It was crucial for this experiment to create X-ray light with precisely the right properties. The researchers were able to accomplish this with so-called spiral zone plates, a special kind of diffractive X-ray lenses through which they sent the light before it hit the sample.

“With the spiral zone plates we were able, in a very elegant way, to give our X-ray light the desired shape and thus an orbital angular momentum. The beams we create in this way are also referred to as optical vortices,” says PSI researcher Benedikt Rösner, who designed and fabricated the spiral zone plates for this experiment.

Jérémy Rouxel, an EPFL researcher and the first author of the new study, explains further: “Helical dichroism provides a completely new kind of light-matter interaction. We can exploit it perfectly to distinguish between enantiomers.”