New study reveals why HIV remains in human tissue even after antiretroviral therapy

Discovery could open the door to new treatments that improve our immune system’s ability to eliminate the stubborn virus, lead to strides in MS research

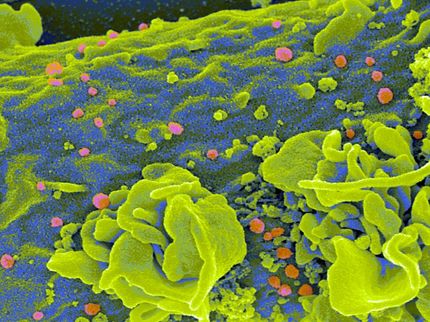

Thanks to antiretroviral therapy, HIV infection is no longer the life sentence it once was. But despite the effectiveness of drugs to manage and treat the virus, it can never be fully eliminated from the human body, lingering in some cells deep in different human tissues where it goes unnoticed by the immune system.

Immunologist Shokrollah Elahi led new research revealing why HIV is able to linger in some cells deep in human tissues, evading the immune system even after retroviral therapy.

Najmeh Bozorgmehr

Now, new research by University of Alberta immunologist Shokrollah Elahi reveals a possible answer to the mystery of why infected people can’t get rid of HIV altogether.

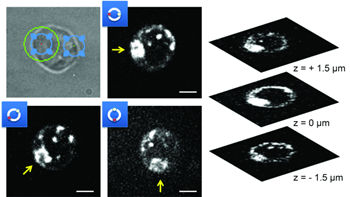

Elahi and his team found that in HIV patients, killer T cells — a type of white blood cells responsible for identifying and destroying cells infected with viruses — have very little to none of a protein called CD73.

Because CD73 is responsible for migration and cell movement into the tissue, the lack of the protein compromises the ability of killer T cells to find and eliminate HIV-infected cells, explained Elahi.

“This mechanism explains one potential reason for why HIV stays in human tissues forever,” he said, adding that the research also shows the complexity of HIV infection.

“This provides us the opportunity to come up with potential new treatments that would help killer T cells migrate better to gain access to the infected cells in different tissues.”

After identifying the role of CD73 — a three-year project — Elahi turned his focus to understanding potential causes for the drastic reduction. He found it is partly due to the chronic inflammation that is common among people living with HIV.

“Following extensive studies, we discovered that chronic inflammation results in increased levels of a type of RNA found in cells and in blood, called microRNAs,” he explained. “These are very small types of RNA that can bind to messenger RNAs to block them from making CD73 protein. We found this was causing the CD73 gene to be suppressed.”

The team’s discovery also helps explain why people with HIV have a lower risk of developing multiple sclerosis, Elahi noted.

“Our findings suggest that reduced or eliminated CD73 can be beneficial in HIV-infected individuals to protect them against MS. Therefore, targeting CD73 could be a novel potential therapeutic marker for MS patients.”

Elahi said the next steps in his research include identifying ways the CD73 gene can be manipulated to turn on in patients living with HIV and off in those with MS.

Most read news

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.