The farm effect: antiallergic properties of the cow’s milk protein BLG

The milk protein is also found in stable dust and ambient air: Together with its binding partners, BLG may contribute to the protection against asthma and allergies

Advertisement

Numerous studies show that a high percentage of children who are born and grow up in a farm environment are protected against asthma, allergies and neurodermatitis. Cattle farms, in particular, have an especially positive effect. The special microbial environment, along with bacterial products and components, represents an important protective factor. But is there one specific bovine factor responsible for the antiallergic properties of cattle farms and cow’s milk? Researchers at the interuniversity Messerli Research Institute in Vienna, in collaboration with national and international working groups, set out to search for as yet undiscovered molecules – and found an essential protein.

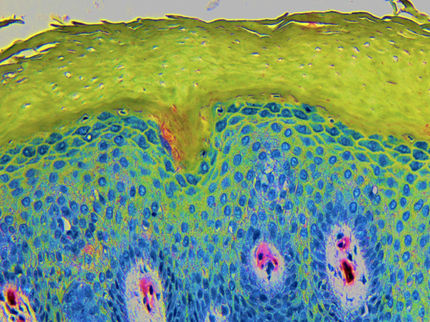

Symbolic image

Unsplash

A pandemic of another kind is currently unfolding, as the incidence of allergic and asthmatic diseases has increased steadily among humans and domestic animals in recent years and seems to only slowly reach a plateau. Growing up on a farm, being in contact with different microbes and their products in the air, hay, dust and straw, can help protect against allergies. However, not all farms are equally protective, with cow farms having a particularly positive effect. Cow stables appear to have an antiallergy barrier around them, a sort of bell jar with a radius of about 300 meters. In addition, drinking unprocessed, natural raw milk seems to reduce the risk of allergies.

A search for clues

Isabella Pali-Schöll, an immunologist and nutritionist in Erika Jensen-Jarolim’s team at the Messerli Research Institute, a joint facility of the Vetmeduni, MedUni Vienna and the University of Vienna, set out to find the answer: Is there a specific factor at cow farms that provides a level of protection against allergies and occurs both in the bovine environment and in cow’s milk?

The milk protein beta-lactoglobulin (BLG) emerged as a hot candidate. BLG makes up a large part of the protein in whey and performs a carrier function for micronutrients such as iron, vitamins and fatty acids. The research group has already shown that BLG plays a role in down-regulating the immune system when complexed with micronutrients such as iron, zinc or vitamin A. Otherwise, it may trigger allergies.

The farm effect

After doing some detective work, the researchers actually found what they were looking for in the farm environment: BLG was detected in large quantities in both, the dust of cattle stables and on the mattresses and pillows in the households. Thus, when people inhale the air on the farm, BLG enters the body. But it does not travel alone: Detailed studies revealed that the BLG in the dust is bound to zinc. And zinc is known to play an important role in the immune system.

“We suspected that the distribution of BLG followed the ‘bell jar’ pattern,” explains first and corresponding author Pali-Schöll, “so we collected ambient air through filters at various locations around a cow stable and analysed the collected samples for the protein. In fact, we were able to measure BLG, in decreasing concentrations, up to almost 300 meters around the stable.”

But how does the protein, which is otherwise mainly found in milk, end up in the stable dust in such large quantities? To answer this question, the scientists collected and analysed urine samples from the cattle. The findings: BLG was detected in the urine of both, female and male cattle.

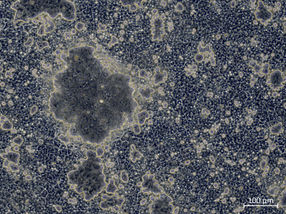

To confirm the antiallergic effect of beta-lactoglobulin, the researchers treated laboratory mice intranasally with stable dust. If the dust contained BLG, the animals’ allergy response was suppressed. In contrast, BLG-free dust did not reduce an allergic immune response in the mice.

According to the researchers, BLG had a protective effect not only against the milk allergen, but also against an unrelated birch pollen allergen. The effect therefore appears to be general, regardless of the allergen in question.

The research conducted by Isabella Pali-Schöll and her national and international collaboration partner represents an important milestone in the elucidation of the farm effect. The findings will also help to translate the gained scientific knowledge into applications for allergy patients. Further research is needed to uncover the different influencing factors involved. It is possible that farming conditions, stress, health status and feeding of the cattle also play a role in determining whether the milk protein can make its contribution to the allergy- and asthma-protective farm effect.