Rear-end Collision on the “Ribosome Highway”

Researchers identify bacterial protein that senses and rescues “stalled” ribosomes

Advertisement

As a molecular machine found in the cells of all organisms, the ribosome is responsible for making new proteins. It reads the blueprint for a certain protein on a messenger molecule – known as messenger RNA (mRNA) – and then converts this information into new proteins. For a number of reasons, this process can fail, leaving the ribosome stalled on the mRNA and bringing synthesis of the protein to a halt. An international research team led by scientists from the Center for Molecular Biology of Heidelberg University (ZMBH) has now identified a bacterial protein called MutS2 that senses and rescues these stuck protein factories. The fact that the next ribosome on the mRNA chain collides with the stalled ribosome plays a key role.

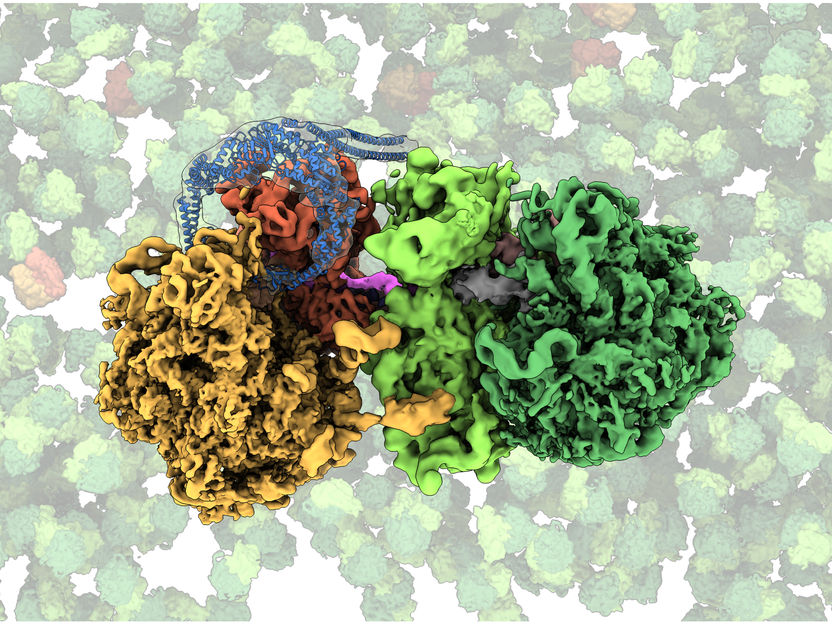

Cryo-EM structure of the collided ribosomes with MutS2. Molecular components were coloured differently (stalled ribosome: orange; collided ribosome: green; MutS2: blue; mRNA: pink).

Sebastian Filbeck (ZMBH)

The blueprints of proteins are stored in the DNA in the cell nucleus, where they are transcribed into mRNA. Bearing the genetic information for a specific protein, the mRNA leaves the nucleus and is transported to the ribosomes, where its information is converted into proteins. “Sometimes ribosomes can get stuck reading the blueprints owing to a defective mRNA molecule, for instance. This is particularly problematic because unfinished proteins are potentially toxic to the cell,” explains ZMBH molecular biologist and working group leader Prof. Dr Claudio Joazeiro. “That is why cells have developed mechanisms that detect stalled ribosomes and mark the incomplete proteins for destruction while still in their birthplace, the ribosome.”

Using high-resolution cryo-electron microscopy, the researchers decoded a major step in this process with the aid of the common soil bacterium, Bacillus subtilis. They were able to precisely characterise how the MutS2 protein, found in nearly one third of all bacteria species, senses stalled ribosomes. MutS2 detects the collision between the stuck ribosome and the next one on the mRNA – a process which ZMBH junior research group leader Dr Stefan Pfeffer likens to a rear-end collision caused by a stalled vehicle on the highway, thus catching the attention of the police.

To rescue ribosomes stuck on the mRNA, MutS2 follows two independent strategies, according to the researchers. “On one hand, MutS2 cuts the mRNA molecule, which subjects it to degradation. On the other hand, MutS2 separates the ribosome into its two subunits, so that it can be recycled for later rounds of protein synthesis. At the same time, the so-called ribosome-associated protein quality control marks the unfinished protein for destruction,” explains Dr Pfeffer. Prof. Joazeiro emphasises that this quality control mechanism is conserved from bacteria to humans. “We thus expect that the understanding of this fundamental process in bacteria will shed light on disease mechanisms in mammals, where failure to degrade unfinished proteins is associated with neurodegeneration and neuromuscular diseases,” adds the researcher.