Study shows how drug plitidepsin inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication inside cells

It acts on cells and prevents the formation of spaces where the virus reproduces

Advertisement

A study co-led by researchers from the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) has shown how the drug aplidin (plitidepsin) acts to inhibit the replication of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus inside human cells: the drug prevents the formation of cellular compartments where the virus material replicates. In this way, it interferes with the cells and prevents the progression of viral infection. Its performance reinforces its potential to combat future variants of SARS-CoV-2, as this step in virus replication is common to all variants of the virus. The study, currently under review, was presented yesterday at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) in Barcelona.

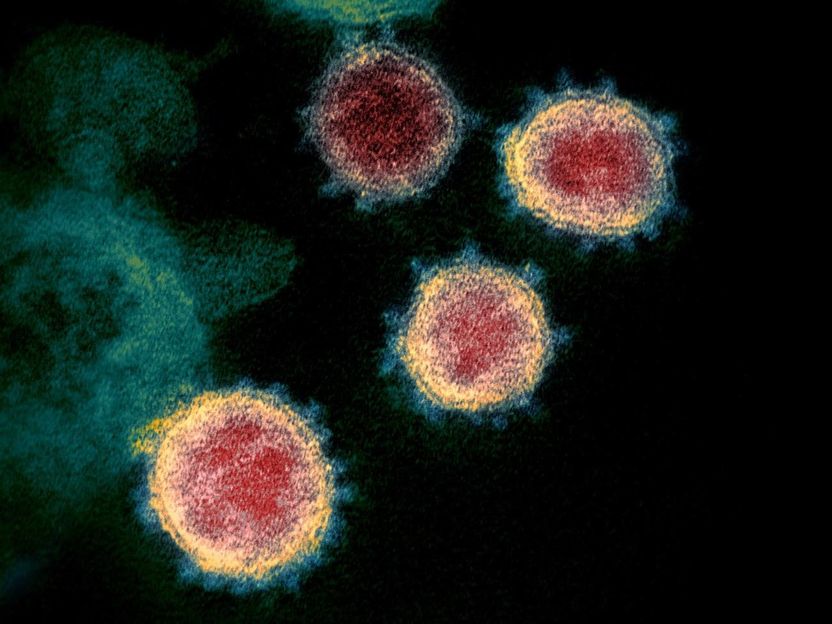

Micrograph of SARS-CoV-2 virions.

NIAID

The drug plitidepsin, marketed as aplidin, has been one of the most effective drugs in blocking SARS-CoV-2 replication in laboratory experiments. "When we launched this study to analyze the antiviral activity of plitidepsin in the cell, we did not expect to discover that its target was at such an early stage of SARS-CoV-2 replication," explains Cristina Risco, a researcher at the National Center for Biotechnology (CNB-CSIC) and co-leader of the study together with researchers from the IrsiCaixa AIDS Research Institute, the Animal Health Research Center (IRTA-CReSA) and the pharmaceutical company PharmaMar.

The drug would block a molecule in the host cell that is necessary for SARS-CoV-2 to form vesicles where new viruses are made. Unlike the vast majority of antivirals, plitidepsin - a drug currently in a Phase III clinical trial - acts on the host cell and not on the virus, blocking essential processes shared by the different SARS-CoV-2 variants. This fact makes it a potential tool to combat not only the current SARS-CoV-2, but also future variants that may emerge.

Preventing SARS-CoV-2 replication from the outset

The research staff conducting the study have demonstrated, in cell cultures in the laboratory, that low amounts of plitidepsin are capable of inhibiting, 48 hours after SARS-CoV-2 infection, the virus' ability to replicate. "Through electron microscopy techniques, we have been able to see how, in the presence of the drug, the double-membrane vesicles, which are the cellular compartments in which the genetic material of SARS-CoV-2 replicates, do not form. We think that this is due to the fact that the non-structural proteins of the virus necessary for the creation of these vesicles are not formed as a consequence of the action of the drug," explains Martin Sachse, researcher at the CNB-CSIC and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and first author of the study.

The team has also verified the non-formation of new viral particles with immunostaining techniques. "We can confirm that plitidepsin acts at a very early point in the viral infection cycle, specifically at the moment when the genetic material of SARS-CoV-2 sends orders for the production of viral proteins that will form the compartments where the viruses replicate their genetic material and direct the synthesis of new viruses," adds Nuria Izquierdo-Useros, principal investigator at IrsiCaixa and co-leader of the study. For their part, the researchers welcome the fact that a low concentration of plitidepsin achieves a potent antiviral effect.

One treatment to combat different variants

Viruses generally have few therapeutic targets for drugs. Moreover, due to their ability to mutate, these targets may no longer be effective. Therefore, finding highly conserved points in the viral replication cycle can be very useful when designing broad-spectrum antiviral drugs. "One of the advantages of plitidepsin over other antivirals is that, instead of acting on the virus directly, it blocks a cell-derived molecule that is essential for SARS-CoV-2 replication. That is why it is a great candidate for combating other SARS-CoV-2 variants that may emerge," conclude Cristina Risco and Nuria Izquierdo-Useros.

Note: This article has been translated using a computer system without human intervention. LUMITOS offers these automatic translations to present a wider range of current news. Since this article has been translated with automatic translation, it is possible that it contains errors in vocabulary, syntax or grammar. The original article in Spanish can be found here.

Original publication

Martin Sachse, Raquel Tenorio, Isabel Fernández de Castro, Jordana Muñoz-Basagoiti, Daniel Perez-Zsolt, Dàlia Raïch-Regué, Jordi Rodon, Alejandro Losada, Pablo Avilés, Carmen Cuevas, Roger Paredes, Joaquim Segalés, Bonaventura Clotet, Júlia Vergara-Alert, Nuria Izquierdo-Useros, Cristina Risco.; "Unraveling the antiviral activity of plitidepsin by subcellular and morphological analysis."; Biorxiv.