Molecular machine in nano cage

What a toy: a tiny gyroscope that would fit in a human cell and that can be controlled from the outside

Advertisement

In cooperation with an international team at the Institute for Basic Science in South Korea, theoretical chemists Dr. Chandan Das and Professor Lars Schäfer from Ruhr-Universität Bochum (RUB) have constructed a molecular gyroscope that can be controlled remotely by light. They also succeeded in characterising the rotational movements of this synthetic nanomachine with computer simulations. The authors describe their findings in the journal “Chem”, published online on 18 January 2022.

Lars Schäfer from Theoretical Chemistry has studied a nanogyroscope with colleagues from South Korea.

© RUB, Marquard

Navigating aircrafts and satellites

Machines enclosed in a cage or casing may display interesting properties. For example, they can convert their energy input into programmed functions. The mechanical gyroscope is one such system – an intriguing toy with the ability to rotate continuously. Some practical applications of gyroscopes include aircraft and satellite navigation systems and wireless computer mice, to name but a few. “In addition to the rotor, another advantage of gyroscopes is their casing, which aligns the rotor in a certain direction and protects it from obstacles,” describes Lars Schäfer.

At the molecular level, many proteins act as biological nanomachines. They are found in every biological cell and perform precise and programmed actions or functions within a confined environment. These machines can be controlled by external stimuli. “In the lab, the synthesis and characterisation of such complex structures and functions in an artificial molecular system presents a huge challenge,” says Schäfer.

Constructed like a ship in a bottle

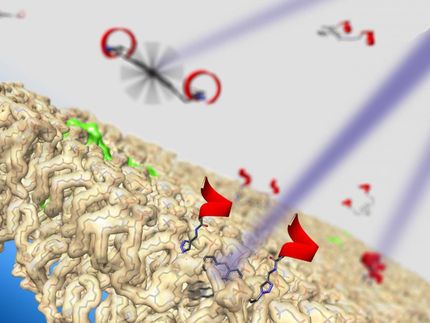

In collaboration with a team headed by Professor Kimoon Kim at the Institute for Basic Science in Pohang, South Korea, the researchers have succeeded in enclosing a supramolecular rotor in a cube-shaped porphyrin cage molecule. Typically, fitting a completed rotor into such cages is complicated by the limited size of the cage windows. In an effort to overcome these limitations, the synthetic chemists in South Korea developed a new strategy that first introduced a linear axis into the cage, which was then modified with a side arm to construct a rotor. “It’s reminiscent of building a ship in a bottle,” illustrates Chandan Das, who, together with Lars Schäfer, performed molecular dynamics computer simulations to describe the rotational motion of the rotor in the cage in atomic detail.

“Our collaboration partners made the intriguing observation that the movement of the rotor in the cage could be set in motion and also switched off again by light as an external stimulus, just like with a remote control,” describes Schäfer. The researchers accomplished this by using light in the UV and visible range to dock a photo-responsive molecule to the cage from the outside and detach it again.

How the molecular gyroscope moves

But how does it work, and what movements does the molecular gyroscope perform after it’s switched on in this manner? “Molecular dynamics computer simulations show that the rotor molecule in the cage exhibits stochastic dynamics, characterised by random 90-degree jumps of the rotor side arm from one side of the cube to an adjacent side,” as Chandan Das explains the results of the theoretical calculations, which can thus elucidate the spectroscopic observations.

The researchers hope that the concept of encasing molecular nanomachines in a molecular cage and remotely controlling their functions will contribute to the understanding of how biological nanomachines work and to the development of smart molecular tools.