The pangenome - key to new therapies

Genetic diversity opens up new ways to treat life-threatening diseases

Advertisement

Aspergillus fumigatus is a fungus that is widespread in the environment and causes life-threatening infections in humans. An international team of researchers has now taken a closer look at the pathogen's great genetic diversity.

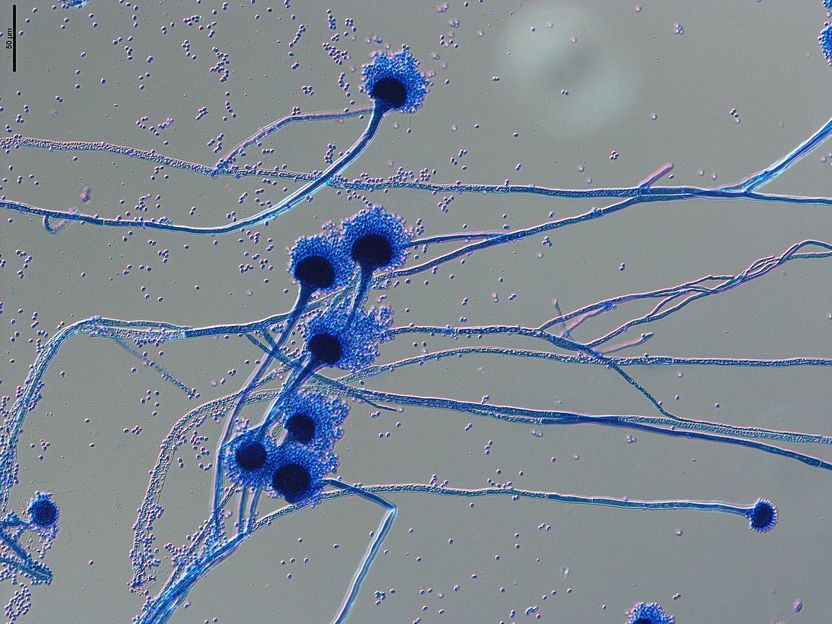

Microscopic image of spore carriers of the human pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. The spores, known as conidia, with a diameter of 1-2 micrometres, are spread through the air and easily enter our respiratory tract, where they can cause severe infections in immunocompromised individuals.

Grit Walther/Leibniz-HKI

Serious fungal infections

The fungus Aspergillus fumigatus causes severe infections in more than 300,000 people worldwide every year. These infections are particularly problematic in immunocompromised patients with a fatality rate up to 50%. Treatment of these diseases relies on triazole antimycotics. However, resistance to these drugs is increasing. In addition, the mortality rate for these drug-resistant infections is up to 25% higher. Moreover, in about 30% of resistant infections, the mechanism of resistance is unknown. Consequently, it is even more complicated to identify and appropriately treat these infections.

"Despite this high number of infections per year, a comprehensive study of the genomic diversity in both clinical and environmental samples has been lacking. In particular, we wanted to elucidate the significance of this genetic diversity in infection and the development of resistance to antimycotics," explains Gianni Panagiotou, head of the Systems Biology and Bioinformatics research group at the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology – Hans Knöll Institute – in Jena (Leibniz-HKI). The researchers are certain that the intra-species genetic diversity of the pathogen also plays an important role in the infection.

The pangenome – genetic diversity explored

In their study, the team of researchers from Jena, Würzburg and Hong Kong, sequenced and analysed a large number of genomes of this widespread mould, including strains from the environment as well as clinical samples. This wealth of genomic information revealed that members of the species differ considerably in their gene content. The authors used this genetic information to define the species' entire gene collection, the so-called pangenome, which encompasses the genetic range of Aspergillus fumigatus. This showed that two-thirds of the genetic information are comprised of so-called core genes that occur in all isolates. The remaining third, however, contains accessory genes that are not found in all isolates and are therefore dispensable for the growth of the fungus, but may play yet undiscovered roles for the fungus in the environment and in human infection.

A specific genetic line causes most infections

Comparing the genomes of fungi from the environment and patient samples, a particular genetic group within the species Aspergillus fumigatus was more likely to cause infections in humans. The genomes of this group had special features. For example, they encoded more transmembrane transporters, iron-binding proteins and enzymes of basic metabolism. These genetic features are interesting as potential targets for new drugs, as they could potentially play a role in the survival of the fungus in the human lung.

In addition, the researchers identified small genetic differences between the isolates in a "genome-wide association study". Certain deviations in the DNA sequence occurred more often in clinical isolates than in environmental isolates. Using this method, the team identified genes that are linked to triazole resistance in ways that are still unknown. "Here we also see promising targets for future therapeutic options. Our attention is therefore focused on the further study of those genes and proteins that are associated with these previously undiscovered resistance mechanisms," says Amelia E. Barber, first author of the study and head of the junior research group Fungal Informatics at Leibniz-HKI.

Hope for new therapies

The authors present the results of their bioinformatic analyses in the latest issue of the journal Nature Microbiology. Their global view of the genetic "toolkit" of Aspergillus fumigatus points the way to possible new therapeutic approaches. Their definition of genes and signalling pathways that are present in all members of the species can be considered as good therapeutic targets. A gene or a metabolic process that is only present in 90% of the disease-causing fungi would be undesirable as a therapeutic target, as 10% of the pathogens would not be affected.

The study also makes us realise that with the genetic diversity within a species, we are always looking at only a snapshot of ongoing evolutionary processes. The genetic make-up of the fungus studied is subject to a high degree of dynamism due to intensive interaction with its environment and can lead to a split into more specialised (sub)species over longer periods of time.

For their work, the researchers were able to rely on cooperations in large research networks. Access to the clinical isolates was made possible by the National Reference Centre for Invasive Fungal Infections based at the Leibniz-HKI, which is supported by the Robert Koch Institute with funds from the Federal Ministry of Health. The BMBF-funded consortium InfectControl provided the framework for the work on triazole resistance and its spread in environment and in clinical isolates. The Cluster of Excellence Balance of the Microverse, funded by the German Research Foundation, enabled the establishment of the junior research group Fungal Informatics and supported the bioinformatic analysis of the enormous data sets.