The genes behind the venom: New technique revolutionizes venom research

New technique makes it possible to show how the unique venom production of a wide range of venomous animals are made up

An international team of scientists has found an innovative, animal-friendly manner for studying venom genes. The technique makes it possible to determine the unique venom production of a wide range of venomous animals that have scarcely, if at all, been studied.

Scorpion species Heterometrus sp., also called the Asian forest scorpion was used in the study.

Arie van der Meijden

A group of scientists from VU Amsterdam and the University of Porto, associated with Naturalis Biodiversity Center and Leiden University, has succeeded in finding the blueprints for proteins in scorpion venom. These blueprints reflect exactly which genes are active in the production of venom.

The venom gland

The technique used is called transcriptomics. It is a method in which patterns of gene expression can be examined. This allows the researchers to observe which genes are active during the production of venom. What makes this approach unique is that the technique has been successfully applied for the first time on the actual venom instead of on venom gland tissue. This means that animals no longer need to be sacrificed to study the gene expression of the venom gland. The method offers many new possibilities for venom research.

Which genes are active?

“Thanks to this technique, we can very precisely see which genes are active at various moments during the venom production,” says Freek Vonk, professor at the VU and researcher at Naturalis. “This snapshot offers the very first possibility to study how various influences, such as nutrition, season, and age, influence the venom production in a single individual.”

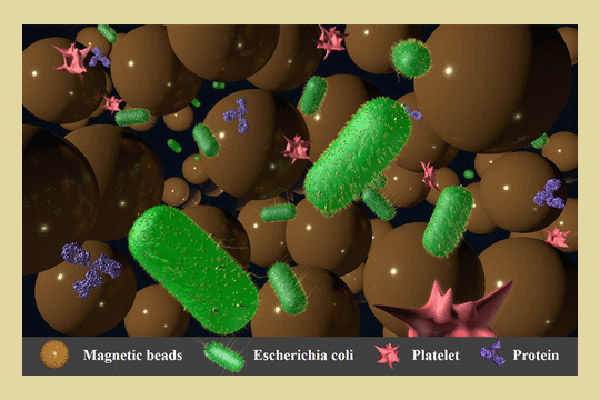

This means that it is now possible to investigate which variations exist in the venom and which factors can influence these variations. “Every venom contains tens to more than hundreds of different venomous substances, also called toxins, which are produced by the venom gland. After a bite or sting, these can have a toxic effect on various systems, such as the nerve endings or blood circulation,” explains Vonk.

Cell remains

“Venom is produced by venomous animals in different ways”, explains Mátyás Bittenbinder, venom expert and PhD student at Naturalis and the VU. “Some animals, such as snakes and centipedes, have venom-producing cells that issue their venom to the storage space in the venom gland in small vesicles, which results in a relatively ‘clean’ venom. Other animals, such as scorpions, allow their venom gland cells to be ‘cut off’ in pieces or even completely disintegrate in the venom storage space and therefore produce a venom that contains many cell remains. Those cell remains contain the substances on which we can perform transcriptomics: mapping which genes are activated to produce which proteins”, continues Bittenbinder.

“The manner of venom production probably explains why the new technique does not work on snakes,” explains Arie van der Meijden. He is a researcher at the University of Porto and the inventor of the innovative approach. “Conversely, the technique now makes it possible to study the venom variations in a large number of venomous animals that have scarcely ever, if at all, been studied, such as scorpions, fish, and even the platypus.”

Better research into venom composition

Furthermore, the method is far easier, purer, and more specific than previously used techniques for venom research. “As a result of this, we can do even better research into how animals produce venom. And that is particularly useful; the toxins in the venom are an important source for finding new, potential drugs, such as drugs to treat cardiovascular diseases,” emphasizes Van der Meijden.