Can proteins bind based only on their shapes?

A team using the nation’s fastest supercomputer to look at protein binding finds that some binding processes are simpler than expected

Advertisement

proteins bind to one another through a complex mix of chemical interactions. What if some proteins bind due to their shapes, a much simpler process? To answer this question, researchers used Summit, the nation’s fastest supercomputer, to model lock-and-key interactions. In these interactions, molecules in the proteins that are binding together must chemically “fit” precisely. The team tested 46 protein pairs that scientists know bind to one another. Next, the team modeled those protein pairs’ assembly on Summit. Out of the 46 pairs tested, 6 assembled based on their complementary shapes more than 50 percent of the time.

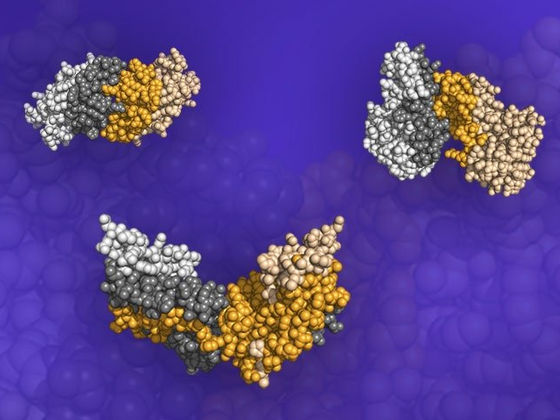

Three protein pair structures. The darkened portions of the structures are the interfaces where the proteins meet and bind.

Image courtesy of Fengyi Gao, University of Michigan and Oak Ridge National Laboratory

The results could have many applications in biological research. For example, the approach could screen drugs for disease treatments or provide scientists with information about how to use proteins as building blocks to design new biological materials. The team plans to study additional proteins that can also bind based on shape—or form even higher order assemblies. Ultimately, the team wants to know the limitation for how protein shapes can evolve to form hierarchical protein structures.

For proteins to successfully bind to one another, one of them acts as a ligand, a molecule that attaches to a target protein, and one of them acts as a receptor, the molecule that receives the ligand. This process involves complex chemical interactions, in which molecules share bonds and change their configurations upon binding. Researchers wanted to see whether they could predict this binding based on shape alone, ignoring the interactions between proteins. From a database of more than 6,000 protein pairs, the team tested 46 pairs that are known to bind to one another and simulated their assembly on Summit, the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility’s 200-petaflop supercomputer.

The team captured six protein pairs that bound based only on shape, with one of the pairs binding more than 94 percent of the time. The team plans to study more proteins that can also bind based on shape—or form even higher order structures. In the future, the team wants to know the limitation for how protein shapes can evolve to form hierarchical protein structures. The team hopes they can eventually predict the binding of protein-protein interfaces in protein clusters or protein crystallization structures.