Learning breaks are good for the memory

Advertisement

We can remember things longer if we take breaks during learning. This phenomenon is known as the spacing effect. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for neurobiology have gained deeper insights into the neuronal basis for this in mice. With longer time intervals between learning repetitions, the animals repeatedly access the same nerve cells - instead of activating others. This may strengthen the connections between the nerve cells in each learning phase, so that knowledge is stored over a longer period of time.

Longer intervals between learning events improve memory and lead to more robust activation patterns in the brain.

© MPI für Neurobiologie / Kuhl

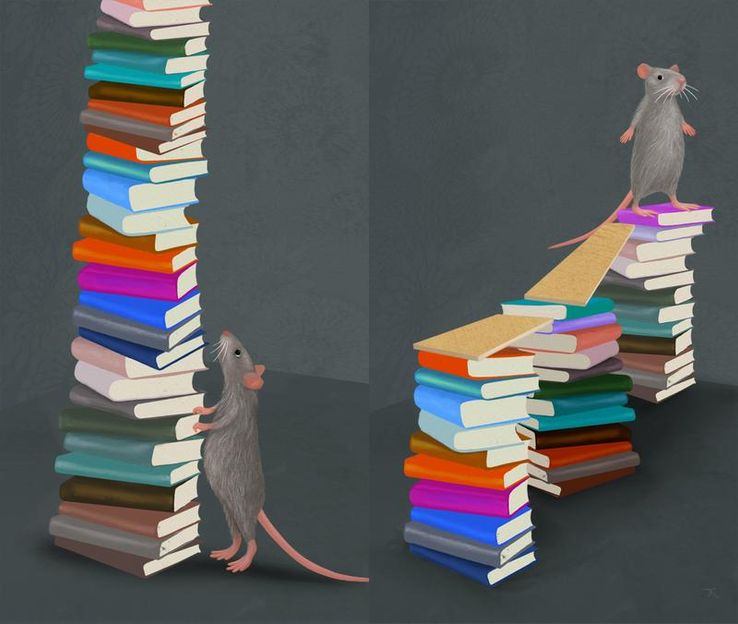

Many of us are familiar with this: the day before an exam, we try to memorize all the material. But as quickly as we learn, so quickly is the laboriously acquired knowledge gone again. The good news: We can counteract this forgetting. With larger time intervals between individual learning phases, we retain the knowledge longer afterwards.

But what happens in the brain during the spacing effect and why are learning breaks so beneficial for our memory? It is assumed that during learning, nerve cells are activated and new connections are made between them. Thus, the learned knowledge is stored and can be retrieved when the same group of nerve cells is activated. In fact, however, we still know very little about how pauses in learning positively influence this process - even though the spacing effect was described more than a century ago and occurs in almost all animal species.

Annet Glas and Pieter Goltstein, neurobiologists in the team of Mark Hübener and Tobias Bonhoeffer, investigated this phenomenon in mice. The animals were asked to remember the position of a hidden piece of chocolate in a maze. The mice were given three consecutive opportunities to explore the maze and find their reward - including pauses of varying lengths. "Mice that we trained with longer pauses between learning phases were not able to remember the position of the chocolate as quickly," explains Annet Glas. "But the next day, the longer the pauses, the better the mice's memory."

During the maze test, the researchers additionally measured nerve cell activity in the prefrontal cortex. This brain region is of particular interest for learning processes, as it is known for its role in complex thinking tasks. The scientists showed that an inactivation of the prefrontal cortex impaired the memory performance of the mice.

"If three learning phases follow each other in quick succession, we intuitively expect the same neurons to be activated," Pieter Goltstein tells us. "After all, it is the same experiment with the same information. After a long pause, on the other hand, it would be conceivable that the brain interprets the subsequent learning phase as a new event and processes it with different neurons."

However, when the researchers compared nerve cell activity during different learning phases, they found just the opposite. During short pauses, the activation pattern in the brain fluctuated more than compared to long pauses: in learning phases that followed each other quickly, the mice activated mostly different neurons. In contrast, after longer pauses, the nerve cells of the first learning phase were used again later.

By using the same nerve cells, the brain may be able to strengthen the connections between them in each learning phase. The contacts don't have to be built "from scratch." "This is why we believe that memory benefits from long pauses," says Pieter Goltstein.

Thus, after more than a century, the study provides deeper insights into the neural processes that explain the positive effect of learning breaks. So with interruptions, we may get there more slowly, but we get something out of our knowledge for much longer. Let's hope we haven't forgotten that by the next exam!

Note: This article has been translated using a computer system without human intervention. LUMITOS offers these automatic translations to present a wider range of current news. Since this article has been translated with automatic translation, it is possible that it contains errors in vocabulary, syntax or grammar. The original article in German can be found here.