Hijacked immune activator promotes growth and spread of colorectal cancer

Through a complex, self-reinforcing feedback mechanism, colorectal cancer cells make room for their own expansion by driving surrounding healthy intestinal cells to death - while simultaneously fueling their own growth. This feedback loop is driven by an activator of the innate immune system. Researchers from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and the University of Heidelberg discovered this mechanism in the intestinal tissue of fruit flies.

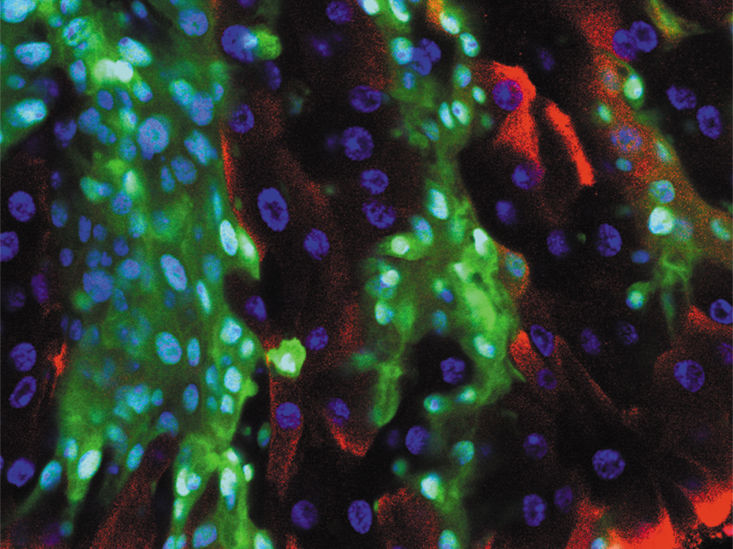

Intestinal tumors cells (green) in Drosophila. Red: dying cells.

© Jun Zhou/DKFZ

Maintaining the well-functioning state of an organ or tissue requires a balance of cell growth and differentiation on the one hand, and the elimination of defective cells on the other. The intestinal epithelium is a well-studied example of this balance, termed "tissue homeostasis": Stem cells in the intestinal crypts constantly produce progenitor cells that further differentiate to replace the rapidly deteriorating mature cells of the intestinal mucosa.

Growth requires a constant dynamic reorganization of tissue architecture: Defective cells must be displaced from the tissue, also by mechanical forces. Tumor cells disrupt this finely balanced structure: They aggressively make room for their own expansion. Until now, it was not understood how exactly they do this.

Jun Zhou, Erica Valentini and Michael Boutros from the German Cancer Research Center and the University of Heidelberg have now investigated these processes in the intestinal epithelium of the fruit fly, which has a similar structure to the intestine of mammals. By blocking the important BMP signaling pathway, the researchers triggered numerous tumors in the fly intestine. Using this model, they uncovered how cancer cells accelerate their own growth through a sophisticated, self-reinforcing feedback effect.

First, tumor cells tear apart the tissue structure by acting on cell adhesion. The resulting altered mechanical adhesion of the intestinal cells activates a stress-sensitive signaling pathway in neighboring intestinal cells, which in turn causes the activation og genes that promote programmed cell death (apoptosis): The team was able to detect large amounts of proteins that initiate aopotosis in the intestinal cells surrounding individual tumor cells.

Presumably due to cytokines released by dying intestinal cells, the growth-promoting JAK/Stat signaling pathway is activated in tumor cells, leading to further tumor spread.

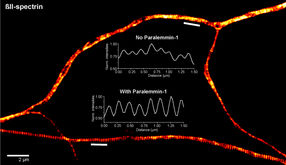

The team also found that the immune activator PGRP-LA is required for this process. When PGRP-LA is turned off, fewer colon cells die through apoptosis and tumor growth also slows down. "The colon cancer cells apparently hijack a signaling molecule of the innate immune system and misuse it for their own purposes. In this way, they kill two birds with one stone: they make room for their expansion by eliminating intestinal cells in their environment - and additionally fuel their own growth," explains study leader Michael Boutros. Future studies will determine whether the same mechanisms also play a role in the spread of human intestinal tumors.