Plant Protector: How plants strengthen their light-harvesting membranes against environmental stress

Advertisement

An international study led by Helmholtz Zentrum München has revealed the structure of a membrane-remodeling protein that builds and maintains photosynthetic membranes. These fundamental insights lay the groundwork for bioengineering efforts to strengthen plants against environmental stress, helping to sustaining human food supply and fight against climate change.

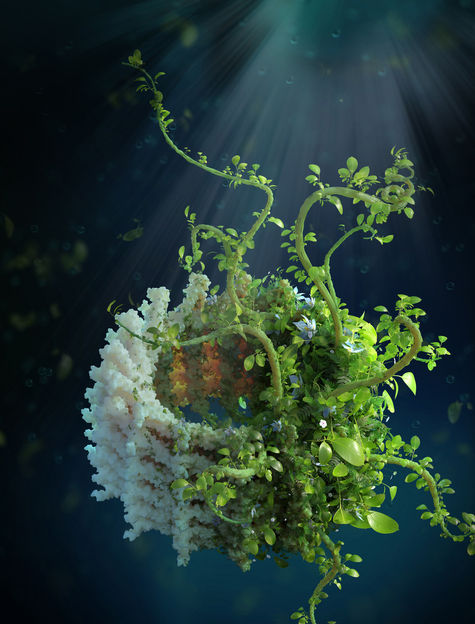

Artistic rendering of the VIPP1 ring structure covered in lush plant life, representing the central role of VIPP1 in constructing and maintaining the photosynthetic thylakoid membranes that enable plants to grow. This study is featured on the cover of Cell (July 8).

Verena Resch. © Helmholtz Zentrum München / Ben Engel

Plants, algae, and cyanobacteria perform photosynthesis, using the energy of sunlight to produce the oxygen and biochemical energy that power most life on Earth. They also adsorb carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the atmosphere, counteracting the accumulation of this greenhouse gas. However, climate change is exposing photosynthetic organisms to increasing environmental stress, which inhibits their growth, and in the long term, endangers the food supply of humankind.

The important first steps of photosynthesis are performed within the thylakoid membranes, which contain protein complexes that harvest sunlight. For decades, it has been known that the protein VIPP1 (vesicle-inducing protein in plastids) is critical for forming thylakoid membranes in almost all photosynthetic organisms – from plants on land to algae and cyanobacteria in the ocean. However, it has remained a mystery how VIPP1 performs this essential function. In the latest issue of the journal Cell, a new study by an international consortium of researchers led by Ben Engel from the Helmholtz Pioneer Campus at Helmholtz Zentrum München reveals the structure and mechanism of VIPP1 with molecular detail.

Building and protecting photosynthetic membranes

The researchers used cryo-electron microscopy to generate the first high-resolution structure of VIPP1. Combining this structural analysis with functional assays revealed how VIPP1 assembles into an interwoven membrane coat that shapes the thylakoid membranes. The research group also used the cutting-edge approach of cryo-electron tomography to image VIPP1 coats within the native environment of algae cells. By using the structural information to make specific mutations to VIPP1, the researchers observed that the interaction of VIPP1 with thylakoid membranes is critical to maintain the structural integrity of these membranes under high-light stress. “Our study shows how VIPP1 plays a central role in both thylakoid biogenesis and adaptation of thylakoids to environmental changes,” explains first author Tilak Kumar Gupta from the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry.

This study lays the foundation for a mechanistic understanding of thylakoid biogenesis and maintenance. It also provides new opportunities for engineering plants that are more resistant to extreme environmental conditions. “Insights into the molecular mechanisms controlling thylakoid remodeling are an important step towards developing crops that not only grow faster, have higher yield and resistance to environmental stress, but also absorb more atmospheric CO₂ to counteract climate change,” says study leader Ben Engel.

International team research

This interdisciplinary study brought together the talents of research teams from the Technische Universität Kaiserslautern (Michael Schroda), Philipps-Universität Marburg (Jan Schuller), Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (Jörg Nickelsen), Okayama University in Japan (Wataru Sakamoto), McGill University in Canada (Mike Strauss), Ruhr-Universität Bochum (Till Rudack), the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry (Wolfgang Baumeister and Jürgen Plitzko) and Helmholtz Zentrum München. “Our study covers a lot of new ground using a wide variety of techniques. This was only possible thanks to the tremendous collective efforts of the researchers in our international consortium,” says Ben Engel.