Gut to brain: nerve cells detect what we eat

Nerve cells of the vagus nerve fulfil opposing tasks: Discovery could play an important role in the development of new therapeutic strategies against obesity and diabetes

The gut and the brain communicate with each other in order to adapt satiety and blood sugar levels during food consumption. The vagus nerve is an important communicator between these two organs. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Metabolism Research in Cologne, the Cluster of Excellence for Ageing Research CECAD at the University of Cologne and the University Hospital Cologne now took a closer look at the functions of the different nerve cells in the control centre of the vagus nerve, and discovered something very surprising: although the nerve cells are located in the same control center, they innervate different regions of the gut and also differentially control satiety and blood sugar levels. This discovery could play an important role in the development of future therapeutic strategies against obesity and diabetes.

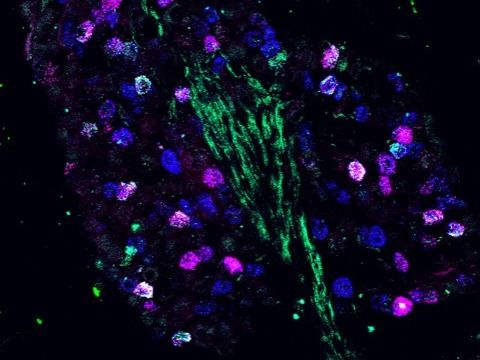

Fluorescence microscopy image of genetically distinct neurons in the nodose ganglion.

Max-Planck-Institut für Stoffwechselforschung

When we consume food, information about the ingested food is transmitted from the gastrointestinal tract to the brain in order to adapt feelings of hunger and satiety. Based on this information, the brain decides, for example, whether we continue or stop eating. In addition, our blood sugar level are adapted by the brain. The vagus nerve, which extends from the brain all the way down to the gastrointestinal tract, plays an essential role in this communication. In the control center of the vagus nerve, the so-called nodose ganglion, various nerve cells are situated, some of which innervate the stomach while others innervate the intestine. Some of these nerve cells detect mechanical stimuli in the different organs, such as stomach stretch during feeding, while others detect chemical signals, such as nutrients from the food that we consume. But what roles these different nerve cells play in transmitting information from the gut to the brain, and how their activity contributes to adaptations of feeding behavior and blood sugar levels had remained largely unclear.

"To investigate the function of the nerve cells in the nodose ganglion, we developed a genetic approach that enables us to visualize the different nerve cells and manipulate their activity in mice. This allowed us to analyze which nerve cells innervate which organ, pointing to what kind of signals they detect in the gut," says study leader Dr. Henning Fenselau. "It also allowed us to specifically switch on and off the different types of nerve cells to analyze their precise function."

Different food activates different nerve cells

In their studies, the researchers focused primarily on two types of nerve cells of the nodose ganglion, which is just one millimeter in size. "One of these cell types detects stomach stretch, and activation of these nerve cells causes mice to eat significantly less," Fenselau explains. "We identified that activity of these nerve cells is key for transmitting appetite-inhibiting signals to the brain and also decreasing blood sugar levels." The second group of nerve cells primarily innervates the intestine. "This group of nerve cells senses chemical signals from our food. However, their activity is not necessary for feeding regulation. Instead, activation of these cells increases our blood sugar level," says Fenselau. Thus, these two types of nerve cells in the control center of the vagus nerve fulfil very different functions.

"The reaction of our brain during food consumption is probably an interplay of these two nerve cell types," Fenselau explains. "Food with a lot of volume stretches our stomach, and activates the nerve cell types innervating this organ. At a certain point, their activation promotes satiety and hence halts further food intake, and at the same time coordinates the adaptations of blood sugar levels. Food with a high nutrient density tends to activate the nerve cells in the intestine. Their activation increases blood glucose levels by coordinating the release of the body's own glucose, but they do not halt further food intake." The discovery of the different functions of these two types of nerve cells could play a crucial role in developing new therapeutic strategies against obesity and diabetes.

Original publication

Diba Borgmann, Elisa Ciglieri*, Nasim Biglari, Claus Brandt, Anna Lena Cremer, Heiko Backes, Marc Tittgemeyer, F. Thomas Wunderlich, Jens C. Brüning, Henning Fenselau; "Gut-brain communication by distinct sensory neurons differently controls feeding and glucose metabolism"; Cell Metabolism; 26. Mai 2021