Hydraulic instability decides who’s to die and who’s to live

Researchers discover that a mechanical cue is at the origin of cell death decision

Advertisement

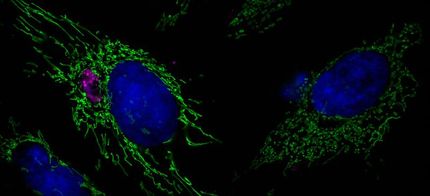

In many species including humans, the cells responsible for reproduction, the germ cells, are often highly interconnected and share their cytoplasm. In the hermaphrodite nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, up to 500 germ cells are connected to each other in the gonad, the tissue that produces eggs and sperm. These cells are arranged around a central cytoplasmic “corridor” and exchange cytoplasmic material fostering cell growth, and ultimately produce oocytes ready to be fertilized.

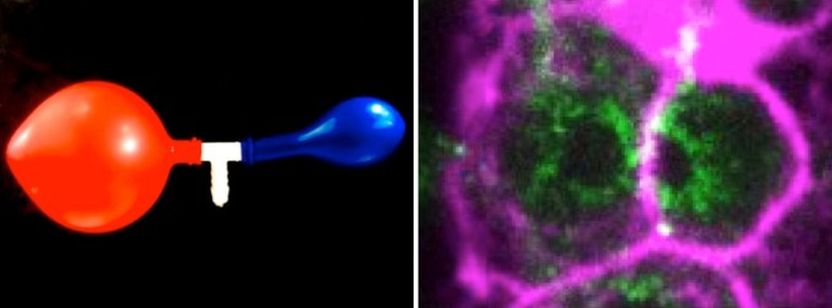

Hydraulic instabilities dictate the volumes of germ cells and balloons

Nicolas Chartier et al. Nature Physics, 20 May, 2021

In past studies, researchers have found that C. elegans gonads generate more germ cells than needed and that only half of them grow to become oocytes, while the rest shrinks and die by physiological apoptosis, a programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms. Now, scientists from the Biotechnology Center of the TU Dresden (BIOTEC), the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG), the Cluster of Excellence Physics of Life (PoL) at the TU Dresden, the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems (MPI-PKS), the Flatiron Institute, NY, and the University of California, Berkeley, found evidence to answer the question of what triggers this cell fate decision between life and death in the germline.

Prior studies revealed the genetic basis and biochemical signals that drive physiological cell death, but the mechanisms that select and initiate apoptosis in individual germ cells remained unclear. As germ cells mature along the gonad of the nematode, they first collectively grow in size and in volume homogenously. In the study just published in Nature Physics, the scientists show that this homogenous growth suddenly shifts to a heterogenous growth where some cells become bigger and some cells become smaller.

The researcher Nicolas Chartier in the group of Stephan Grill, and co-first author of the study, explains: “By precisely analyzing germ cell volumes and cytoplasmic material fluxes in living worms and by developing theoretical modeling, we have identified a hydraulic instability that amplifies small initial random volume differences, which causes some germ cells to increase in volume at the expense of the others that shrink. It is a phenomenon, which can be compared to the two-balloon instability, well known of physicists. Such an instability arises when simultaneously blowing into two rubber balloons attempting to inflate them both. Only the larger balloon will inflate, because it has a lower internal pressure than the smaller one, and is therefore easier to inflate.” This is what is at play in the selection of germ cells: such pressure differences tend to destabilize the symmetric configuration with equal germ cell volumes, so-called hydraulic instabilities, leading to the growth of the larger germ cell at the expense of the smaller one. By artificially reducing germ cell volumes via thermoviscous pumping (FLUCS method: focused-light-induced cytoplasmic streaming), the team demonstrated that the reduction in cell volumes leads to their extrusion and cell death, indicating that once a cell is below a critical size, apoptosis is induced and the cell dies.

By using confocal imaging, the researchers could image the full organism of the living worm to receive a global and precise picture of the volumes of all the gonad cells, as well as the exchange of fluids between the cells. Stephan Grill, Speaker of the Cluster of Excellence Physics of Life (PoL) and supervisor of the multidisciplinary work, adds “These findings are very exciting because they reveal that the life and death decision in the cells is of mechanical nature and related to tissue hydraulics. It helps to understand how the organism auto-selects a cell that will become an egg. Furthermore, the study is another example of the excellent cooperation between biologists, physicists and mathematicians in Dresden.”