Solving the oldest problem in microbiology

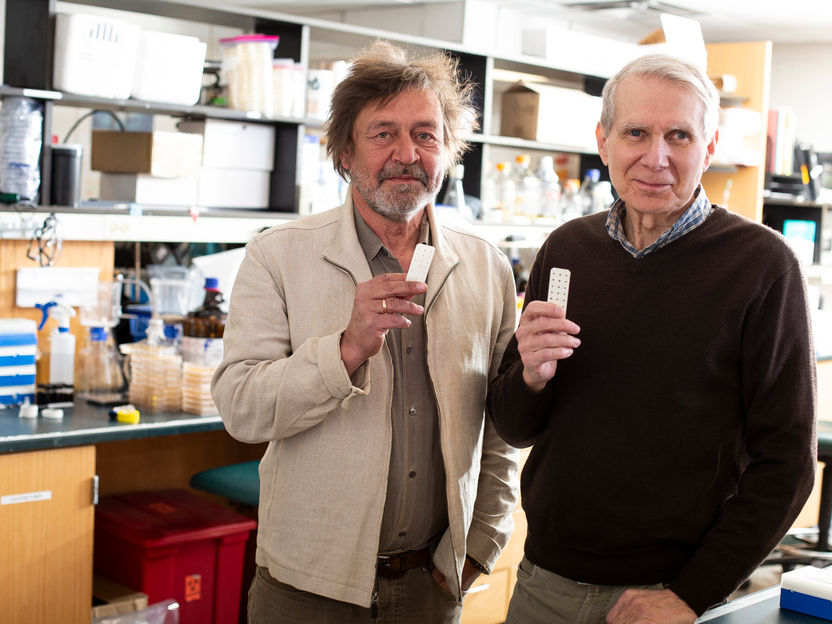

Kim Lewis and Slava Epstein named European Inventor Award 2021 finalists

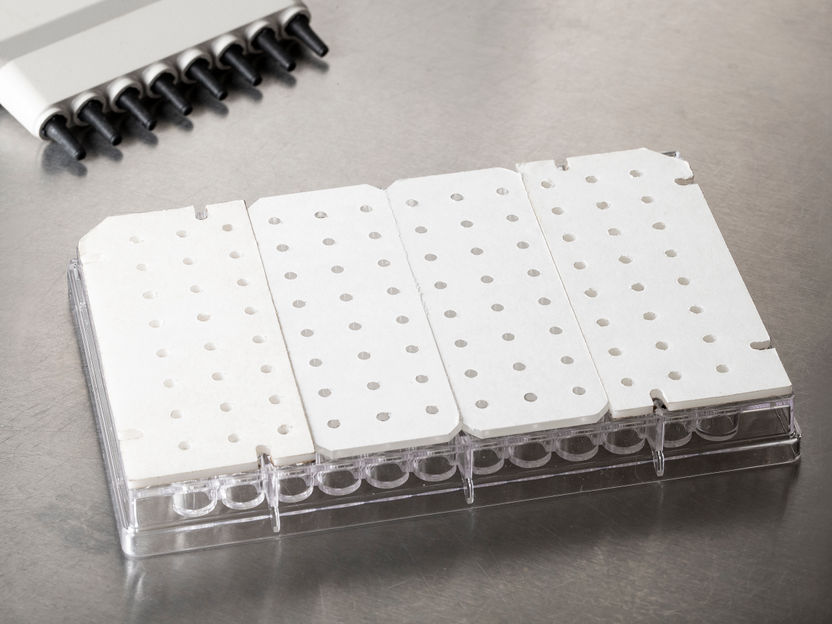

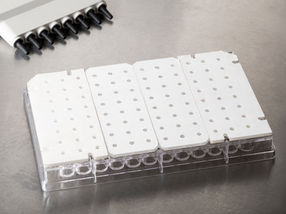

The European Patent Office (EPO) announces that renowned US microbiologists Kim Lewis and Slava S. Epstein have been nominated as finalists in the "Non-EPO countries" category of the European Inventor Award 2021. They have developed a device that enables scientists to separate and incubate single strains of bacteria in their natural environment. Their invention, the iChip - a thumb-sized plastic chip with miniscule holes - allows a greater number and variety of microorganisms to be grown in laboratories, solving a longstanding problem in microbiology.

US microbiologists nominated for European Patent Office (EPO) prize for device that enables scientists to grow previously ‘unculturable' single microbe cells

Invention separates new microbe cells and grows them using nutrient-rich soil taken from their native environments. As a result, scientists can culture a far wider range of microbes, leading to the discovery of new drugs capable of tackling ‘superbugs' immune to existing antibiotics

The iChip has gone on to help researchers cultivate about 80 000 strains of previously unculturable organisms, leading to over 50 potential candidates for new antibiotics. The success of the device enabled Lewis and Epstein, who both emigrated from the USSR to pursue their careers, to establish a privately held company, which has been commercialising the iChip since 2010.

"Lewis and Epstein have created a tool that enables scientists to access and cultivate microorganisms that were not available before," says EPO President António Campinos, announcing the European Inventor Award 2021 finalists. "This could help researchers find new antibiotics, tackle drug resistance and, ultimately save lives. And they show how patents play an important role in turning innovation into a business."

The winners of the 2021 edition of the EPO's annual innovation prize will be announced at a ceremony starting at 19:00 CEST on 17 June which has this year been reimagined as a virtual event for a global audience.

Tackling a dark, age-old anomaly

The age-old problem for microbiologists has been to tap into the potential of the 99% of microbes that cannot be cultured in the lab. Only 1% of microbial cells will produce colonies in a petri dish, and from this, scientists have derived virtually every antibiotic used in modern medicine. However, overuse of these antibiotics has led to drug resistance, rendering treatments ineffective and exposing human populations to dangerous infections.

Trying to grow more bacteria in the lab was seen as an unproductive field of work. Scientists wrote off most bacteria as ‘dark matter' - a term used in astronomy for an inscrutable substance that may make up most of the universe but cannot be seen. For microbiologists, the reality was that most strains of bacteria were simply inaccessible in the lab.

Growing up in the USSR gave both inventors a different perspective on things, which helped them bring fresh ideas to the field of microbiology. After working at Moscow University - where the pair vaguely knew each other - both emigrated separately to the US. Coincidentally, they both ended up at Northeastern University in Boston in the early 2000s, where they were reintroduced by a mutual friend.

At Northeastern, the pair began collaborating to find ways of cultivating new bacterial species, convinced that a new approach was needed and that the problem could be overcome. A key breakthrough came when Epstein and Lewis recognised that nutrients from bacteria's native soil was the key ingredient missing in conventional petri dishes. However, the difficulty lay in separating strains of bacteria from another. Unlike pure colonies in a lab, bacteria in nature intermingles, making it impossible to separate single strains.

What was needed was a device capable of isolating and incubating single strains of bacteria in their natural environment - garden soil, for example, and the concept for the iChip (short for isolation chip) was born. After trial and error, which involved burying the device in the ground to collect bacterial samples, Lewis and Epstein successfully developed their thumb-sized prototype. "I am an optimist," says Epstein. "When you are sure that you will overcome challenges, then facing challenges become truly exciting."

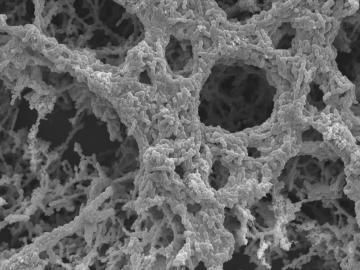

The device works by capturing single microbe cells and exposing them to nutrient-rich soil through a polycarbonate membrane with very thin pores of between 20 and 30 nanometres. This creates an effect a little like a plastic supermarket bag with tiny holes. Bacterial cells are isolated in compartments, sustained by nutrients from soil that are able to pass through the membrane.

In 2002, Epstein and Lewis reported a 300-fold increased bacterial growth in their new device compared to a conventional petri dish. That same year, the pair filed a European patent application (for a method to isolate and cultivate microorganisms), which was granted in 2008.

A year later in 2003, Lewis and Epstein founded the privately held SME NovoBiotic Pharmaceuticals, LLC to bring the iChip to market. The iChip was officially launched in 2010. "It would not have been possible to start a company without filing patent applications," says Lewis. "The first question that an investor asks is what you own, and the only thing we owned was our IP."

A tool to develop next-generation antibiotics

Since its launch, Lewis and Epstein's iChip has helped researchers to develop potential candidates for new antibiotics. These include teixobactin, the first new class of antibiotics announced in decades. The inventors' company is currently running studies relating to teixobactin that will enable them to start phase I trials in 2022, according to Lewis.

The success of the iChip, and the inventors' inspiring story of emigration and collaboration at Northeastern - has brought the pair a measure of fame. Cultivation tools designed in Epstein's lab at Northeastern have been named among the top 100 discoveries by Discover Magazine.

For Epstein, establishing a commercial enterprise was the best way to deliver results. Their iChip is not purely academic work, but a tool designed to address the needs of today. As a result, both continue to divide their time between their academic posts and consulting on iChip-related projects.

Antimicrobial resistance continues to present a critical health threat. Without next-generation antibiotics, ‘superbugs' could claim up to 10 million lives per year by 2050. With the global clinical microbiology market estimated at EUR 8.3 billion in 2016, and expected growth at a compound annual growth rate of 6.7% to reach EUR 15.2 billion by 2025, Lewis and Epstein's company is well placed to play a key role in this expansion.

Their invention is also an excellent example of how a low-tech solution can transform scientific practices, and ultimately bring benefits to citizens. In addition to contributing to tackling antimicrobial resistance, the iChip - as a way of allowing researchers to isolate and study bacteria- has the potential to help develop drugs to treat other diseases, such as anti-cancer agents, anti-inflammatories and immunosuppressives.