Upgrade for CRISPR/Cas: Researchers knock out multiple genes in plants at once

Until now, creating multiple mutations was a much more complex process

Advertisement

Using an improved version of the gene editing tool CRISPR/Cas9, researchers knocked out up to twelve genes in plants in a single blow. Until now, this had only been possible for single or small groups of genes. The approach was developed by researchers at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) and the Leibniz Institute of Plant Biochemistry (IPB). The method makes it easier to investigate the interaction of various genes.

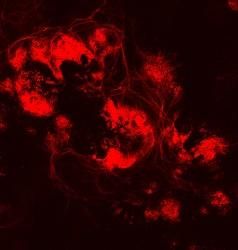

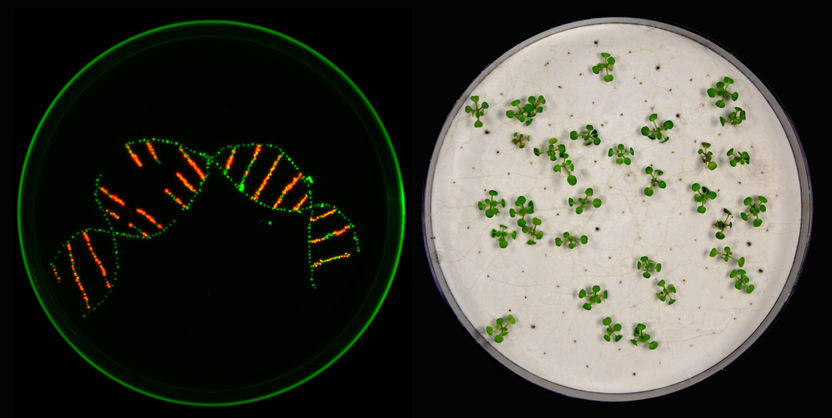

In their work, the researchers used markers to distinguish between different plant seeds. No difference can be seen with the naked eye. Under UV light, however, transgenic seeds appear red, non-transgenic seeds green. (left picture)

Jessica Lee Erickson

The inheritance of traits in plants is rarely as simple and straightforward as Gregor Mendel described. The monk, whose experiments in the 19th century on trait inheritance in peas laid the foundation of genetics, in fact got lucky. "In the traits that Mendel studied, the rule that only one gene determines a specific trait, for example the colour of the peas, happened to apply," says plant geneticist Dr Johannes Stuttmann from the Institute of Biology at MLU. According to the researcher, things are often much more complicated. Frequently there are different genes that, through their interaction with one another, result in certain traits or they are partly redundant, in other words they result in the same trait. In this case, when only one of these genes is switched off, the effects are not visible in the plants.

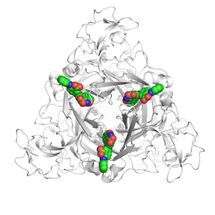

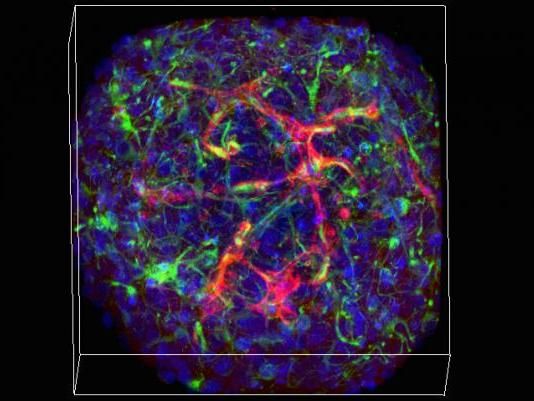

The scientists at MLU and IPB have now developed a way to study this complex phenomenon in a more targeted way by improving CRISPR/Cas9. These gene editing tools can be used to cut the DNA of organisms at specific sites. The team built on the work of biologist Dr Sylvestre Marillonnet who developed an optimised building block for the CRISPR/Cas9 system at the IPB. "This building block helps to produce significantly more Cas9 enzyme in the plants, which acts as a scissor for the genetic material," explains Stuttmann. The researchers added up to 24 different guide RNAs which guide the scissor enzyme to the desired locations in the genetic material. Experiments on thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana) and the wild tobacco plant Nicotiana benthamiana proved that the approach works. Up to eight genes could be switched off simultaneously in the tobacco plants while, in the thale cress, up to twelve genes could be switched off in some cases. According to Stuttmann, this is a major progress: "As far as I know, our group has been the first to successfully address so many target genes at once. This may make it possible to overcome the redundancy of genes," says the biologist.

Until now, creating multiple mutations was a much more complex process. The plants had to be bred in stages with a single mutation each and then crossed with one another. "This is not only time-consuming, it’s also not possible in every case," says Stuttmann. The new approach developed at the MLU and the IPB overcomes these disadvantages and could prove to be a more efficient method of research. In future, it will also be possible to test random combinations of several genes in order to identify redundancies. Only in the case of conspicuous changes in the plant’s traits would it then be necessary to specifically analyse the genetic material of the new plants.