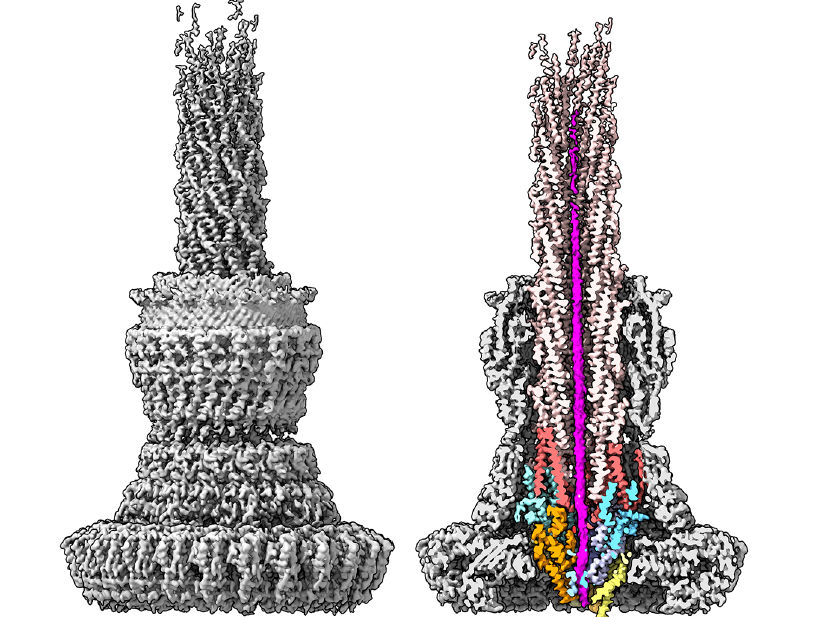

Bacteria needle under the electron microscope

Researchers watch injectisome of gram-negative bacteria in action for the first time

Advertisement

For the first time, researchers have revealed the syringe-like type-III secretion system of Gram-negative bacteria in action. In the research study, published in Nature Communications, the group of Thomas Marlovits from the Centre for Structural Systems Biology (CSSB) at the DESY campus provides new insights into how pathogenic bacteria such as Salmonella infect human cells. According to the researchers, visualizing this at the molecular level helps further our understanding of host-pathogen interactions and contributes to the development of novel therapies for the treatment of bacterial infections and other diseases.

Structure of the type III secretion system of Salmonella, imaged with the cryo-electron microscope. The section through the complex (right), shows in magenta a bacterial toxin protein during transport through the narrow needle cannula. For successful transport, toxin proteins must unfold completely and take on a new shape. The proteins that form the export apparatus and the needle filament secretion channel are also stained. The researchers were able to observe a bacterial protein inside the needle complex for the first time using the high-resolution cryo-electron microscope at CSSB.

CSSB, Thomas C. Marlovits

To infect its human host, many Gram-negative bacteria such as Salmonella or plague bacteria rely on a type III secretion system also known as the injectisome. Each individual bacterium has several syringe-shaped injectisomes protruding from its surface. As their name implies, injectisomes are responsible for injecting bacterial proteins into human cells. Once inside the cell, these bacterial proteins invade cellular tissue and help ensure the spread of infection.

The Marlovits group has been investigating the molecular mechanisms of the injectisome’s needle complex for several years. “The needle complex is a cylindrical structure and represents the most prominent part of the injectisome,” explains Marlovits. “It provides bacterial proteins with smooth passage from the bacterium’s cytoplasm across several membranes directly into human host cells.”

In fact, it has been reported that as many as 60 bacterial proteins can travel through the needle complex in one second. While this rapid rate of secretion is advantageous for the bacterium, it hinders the researchers’ ability to visualize and understand this essential process. “To help overcome this challenge, we trapped a single bacterial protein inside the needle complex with a trick,” explains Sean Miletic, one of the study's main authors. Miletic’s colleague Jiri Wald was then able to capture high resolution images of the protein’s subtle movements inside the needle complex using a cryo electron microscope at CSSB.

The high-resolution images not only provided new insights into the structure of the needle complex but also confirmed the essential role of its export apparatus (EA) which functions as an entry portal. “The EA’s structural elements function together as both a gate and guide, to engage and steer bacterial proteins towards the tip of the needle,” explains Dirk Fahrenkamp from the research team, who built an atomic model of the needle complex based on the images.

Ultimately, understanding and visualizing the molecular mechanisms employed by bacteria to invade human cells at atomic resolution is essential for the development of novel therapies which are able to fight infections in a targeted and intelligent manner. “While these results enrich our understanding of the type three secretion system, this study is also notable in that it was truly a group effort,” explains Marlovits. “Not only did each of the paper’s four first authors contribute their own vital expertise but the collaboration efforts of the cryo-EM facility and the support of the CSSB media kitchen were essential to the success of this study.”