Defense alliance: Microscopic enemies targeted

Bacteria join forces against common enemy

Advertisement

Two bacterial species cooperate chemically with each other to fight off amoebae that actually consume them. A team of researchers from Jena discovered this cooperation-based defense mechanism of bacteria. Natural substances play an important role in this process. Originally responsible for the communication and interaction of microorganisms, they can provide impulses for the development of new drugs such as antibiotics.

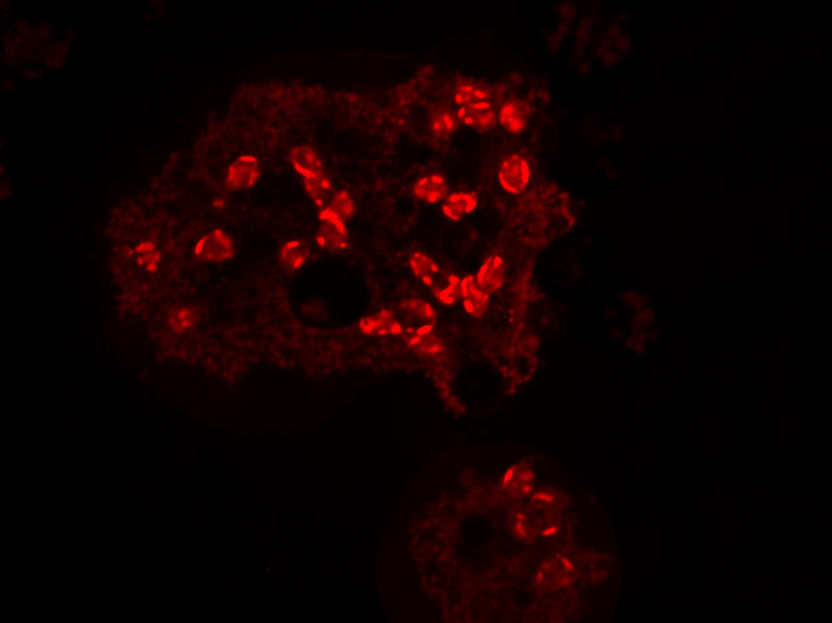

The microscope image shows an amoeba killed by the bacteria.

Ruchira Mukherji, Leibniz-HKI

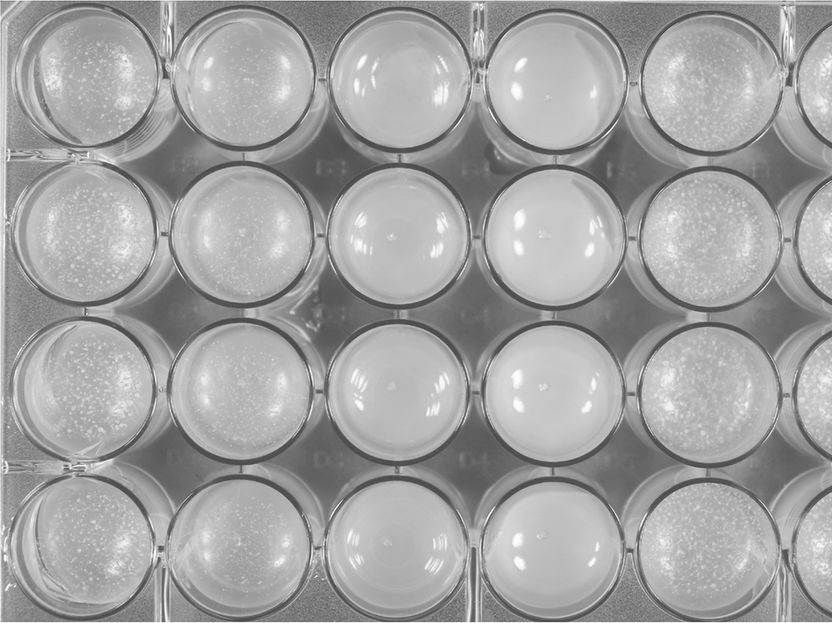

n a multiwell plate, researchers can simultaneously test 24 bacterial strains to see if they are eaten by amoebae. If a bacterium proves to be edible, the amoebae develop fruiting bodies that can be identified as small dots.

Pierre Stallforth, Leibniz-HKI

Microorganisms naturally live in communities. They interact with each other and with their environment. Their coexistence is regulated by natural substances, small molecules that cause complex subsequent reactions through their activity. These can be very different: Some species are well-disposed towards each other, others fight each other to the death. Representatives of the two bacterial genera Pseudomonas and Paenibacillus have found a way to defend themselves together against their predators, amoebae. "The two bacterial species and the amoebae share their habitat in nature. They live in the forest floor, for example, and in the process the bacteria serve as food for the amoebae," says Pierre Stallforth from the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology - Hans Knöll Institute (Leibniz-HKI) in Jena.

However, as he and his team discovered, the bacteria are not defenceless against the amoeba's attacks. "If Pseudomonas and Paenibacillus join forces, they can successfully defend themselves and even finish off their predator," said Stallforth. Pseudomonas forms the lipopeptide syringafactin, which is cleaved by the peptidases of Paenibacillus. The resulting compounds have a sometimes lethal effect on the amoebae. "We were able to show that an organic compound from one bacterium stimulates the other to produce enzymes. And these enzymes break down the organic compound into smaller elements. These are active agents against the threat and kill the amoeba. By working together to produce a chemical weapon, the bacteria escape their fate of being eaten. Cooperation can be helpful. We think we have discovered just one of many examples of this cooperative strategy," Stallforth explains. The authors of the study report on the natural products involved in this process in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A..

The researchers only got on the trail of this defensive alliance because they cultivated the microorganisms involved together instead of in isolation from each other, as is usually the case. "The lack of new active ingredients for drugs requires us to break new ground in natural products research. We try to create conditions in our laboratories that are as close to nature as possible, because we now know that microorganisms behave differently in communities than in pure cultures," says Stallforth, who is also involved in the Jena Cluster of Excellence "Balance of the Microverse". This interdisciplinary research network focuses on microbiome research. The cluster scientists investigate the interaction of microorganisms in different habitats in order to derive overarching principles. These provide clues for solving urgent societal challenges such as antibiotic resistance, pesticide use in agriculture and climate change.

Note: This article has been translated using a computer system without human intervention. LUMITOS offers these automatic translations to present a wider range of current news. Since this article has been translated with automatic translation, it is possible that it contains errors in vocabulary, syntax or grammar. The original article in German can be found here.