Embryonic development in a Petri dish

3D cell culturing technique could replace mouse embryos

Advertisement

By growing mouse stem cells in a special gel, a Berlin research team succeeded to grow structures similar to parts of an embryo. The trunk-like structures develop the precursors for neural, bone, cartilage and muscle tissues from cellular clumps within five days. This could allow the investigation of the effects of pharmacological agents more effectively in the future – and on a scale that would not be possible in living organisms.

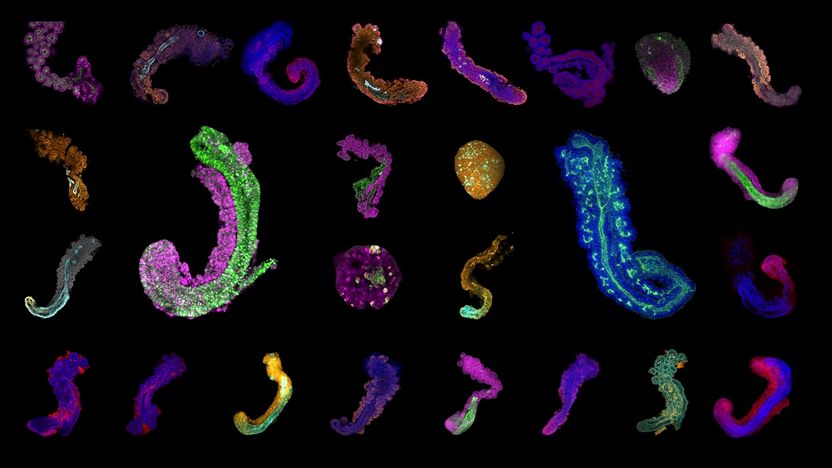

Collage of fluorescent microscopic images of Trunk-Like-Structures generated from stem cells at several stages of their development in a dish. The trunk-like-structures have been stained for expression of different key developmental genes (colors). Some have been treated with drugs that target important developmental pathways, which leads to neural tube defects and overproduction of somites arranged like a bunch-of-grapes (e.g. top left).

© Dennis Schifferl, Adriano Bolondi, Polly Burton, Jesse Veenvliet - MPI f. Mol. Genet.

It would certainly spare mothers the hardships of pregnancy, but mammals do not grow in eggs. In a way, this is also impractical for science. While embryos of fish, amphibians or birds can be easily watched growing, mammalian development evades the gaze of the observer as soon as the embryo implants into the uterus. This is precisely the time when the embryo undergoes profound changes in shape and develops precursors of various organs – a highly complex process that leaves many questions unanswered.

But now a research team at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin succeeded in replicating a central phase of embryonic development in a cell culture approach by growing the core portion of the trunk from mouse embryonic stem cells for the first time. The method recapitulates the early shape-generating processes of embryonic development in the Petri dish.

The structures are roughly a millimeter in size and possess a neural tube from which the spinal cord would develop. Furthermore, they have somites, which are the precursors of skeleton, cartilage and muscle. Some of the structures even develop the precursors of internal organs such as the intestine. After about five days, the parallels to normal development end.

“This model of embryonic development starts a new era,” says Bernhard G. Herrmann, Director at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics and Director of the Institute of Medical Genetics at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. “This allows us to observe embryogenesis of the mouse directly, continuously, and with large parallel numbers of samples – which would not be possible in the animal.”

It is considered quite easy to isolate early embryos from the tube or the uterus and grow them in the Petri dish, as long as they are still free to move. But once the embryo has implanted in the endometrium, isolation becomes extremely difficult. “We can obtain more detailed results more quickly, and without the need for animal research,” says Alexander Meissner, who like Herrmann is Director at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics and jointly supervised the study. “Of the more complex processes such as morphogenesis, we usually only get snapshots – but this changes with our model.”

A gel provides support and spatial orientation

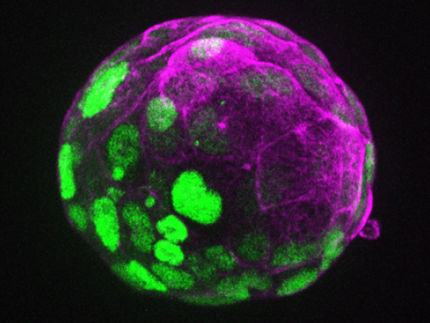

So far, it has only been possible to grow cell clusters from embryonic stem cells, so-called gastruloids. “Cellular assemblies in gastruloids develop to a similar extent like in our trunk-like structures, but they do not assume the typical appearance of an embryo” says Jesse Veenvliet, one of the two lead authors of the study. “The cell clusters lack the signals that trigger their organization into a meaningful arrangement.”

In the cell culture, the required signal is generated by a special gel that mimics the properties of the extracellular matrix. This jelly-like substance consists of a complex mixture of extended protein molecules that is secreted by cells and is found throughout the body as an elastic filling material, especially in connective tissues. The utilization of this gel is the crucial “trick” of the new method. “The gel provides support to the cultured cells and orients them in space; they can distinguish inside from outside, for example,” says Veenvliet. It also prevents secreted molecules such as the matrix protein fibronectin from leaking into the cell culture medium. “The cells are able to establish better communication, which leads to better self-organization.”

Cells with similar properties as in the embryo

After four to five-days, the team dissolved the structures into single cells and analyzed them individually. “Even though not all cell types are present in the trunk-like structures, they are strikingly similar to an embryo of the same age,” says Adriano Bolondi, who is also lead author of the paper. Together with bioinformatician Helene Kretzmer, Bolondi and Veenvliet compared the genetic activity of the structures with actual mouse embryos. “We found that all essential marker genes were activated at the right time in the right places in the embryoids, with only a small number of genes being out of line,” says Bolondi.

The researchers introduced a mutation with known developmental effects into their model and could recreate the results from “real” embryos, further validating their model. They also provide examples of manipulating the developmental process with chemical agents.