COVID-19: contact with cold viruses apparently offers no protection

In contrast, the immune memory could instead contribute to severe disease progressions

Advertisement

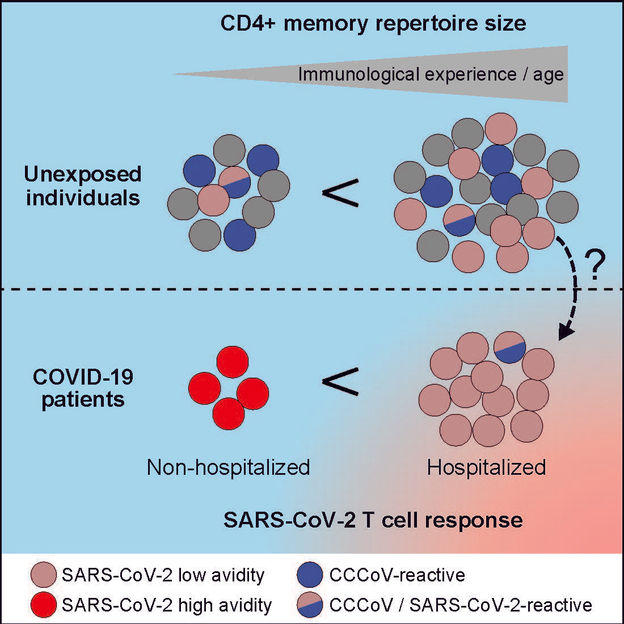

Covid-19 can progress very differently, from symptom-free right through to life-threatening, and severe cases particularly occur in older patients. The reasons for this are unclear. Before the appearance of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, many people had already been exposed to other coronaviruses, such as those which cause the common cold. Therefore, the hypothesis arose that these prior exposures could possibly afford better immune protection, even against infection with SARS-CoV-2. Members of the Cluster of Excellence "Precision Medicine in Chronic Inflammation" (PMI) in Kiel have investigated this hypothesis. They were able to show that people who have not yet been infected with SARS-CoV-2 do in fact have specific immune cells, so-called memory T cells, which can also recognize SARS-CoV-2 as a foreign body. However, these "pre-existing" memory T cells do not appear to be particularly good at recognizing and fighting a SARS-CoV-2 infection, because they only bind to the virus very weakly. Instead, these memory cells could in fact contribute to a more severe disease progression. The research team, led by Professor Petra Bacher and Professor Alexander Scheffold from the Institute of Immunology at Kiel University (CAU) and the University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein (UKSH), Campus Kiel, together with colleagues at the university hospitals in Cologne and Frankfurt, recently published their results in the scientific journal Immunity.

Among COVID-19 patients with a mild progression, the research team primarily found T cells which recognize the virus very well, whereas the T cells in patients with severe progression only recognize SARS-CoV-2 very badly, just like the pre-existing memory cells of individuals who previously had no contact with the novel coronavirus.

© Immunity Cell Press

In the course of their life, a person’s immune system comes into contact with numerous foreign bodies, such as pathogens. When it encounters a previously unknown pathogen, then so-called naive T cells are activated, which - after a learning phase lasting a few days - drive the immune reaction to the new pathogen. After the acute immune reaction, this "knowledge" of the immune system about the specific pathogen is stored in the body in the form of memory T cells. If the immune system comes into contact with the same pathogen again, then these memory cells are activated and can fight the pathogen faster and more effectively than naive cells. Similar pathogens, for example different strains of coronaviruses, can also trigger these memory cells in a so-called cross-reaction, which thereby also fight such pathogens faster.

"Previous work had already shown that people who previously had no contact with the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 still had memory T cells which can recognize SARS-CoV-2 as a pathogen. But it was not clear where these come from, and in particular what influence they have on fighting SARS-CoV-2. One hypothesis was that they come from contact with coronavirus strains for the common cold, and cross-react to SARS-CoV-2. Our focus was therefore on these existing memory cells. We wanted to examine whether these really lead to better protection against a SARS-CoV-2 infection," explained Professor Alexander Scheffold, Director of the Institute of Immunology at the CAU and the UKSH, Campus Kiel, and member of the Cluster of Excellence PMI.

SARS-CoV-2 memory cells do not only arise from colds

To do so, they investigated the immune cells in blood from donors who previously had no contact with SARS-CoV-2. They were able to show that people without prior contact with the virus do in fact have these memory cells, which also recognize SARS-CoV-2 as a foreign body. "However, contrary to our expectation, younger people - who are more likely to suffer from the common cold - do not have a greater number of these cells. In addition, only a small percentage of these cells also react to the common cold coronaviruses. Therefore, it seems that the memory cells have little to do with previous contacts with common cold coronaviruses," said Scheffold. "Rather, it seems that during the course of life, the repertoire of memory cells against many different pathogens increases, and thereby also the probability that this will include memory cells which recognize SARS-CoV-2 by chance. This memory cell repertoire, which increases with each infection, can therefore also be referred to as the "immunological age", that also actually increases with the biological age," continued Scheffold.

But although these memory cells are present in everyone, they are apparently not involved in fighting a SARS-CoV-2 infection. This is thought to be due to their quality: "Although these memory T cells recognize the SARS-CoV-2 virus, they don’t do so particularly well. Therefore, they are probably not able to ensure that the virus is fought successfully," explained the lead author Professor Petra Bacher, Schleswig-Holstein Excellence-Chair early career group leader for "Intestinal Immune Regulation" at the Institute of Immunology at the CAU. In fact, in COVID-19 patients with mild progression, the research team primarily found T cells which recognize the virus very well. "Here, the underlying immune reaction could be based on naive T cells, i.e. the T cells which support the immune reaction to the virus here could have arisen from naive T cells, and not from memory cells," explained Bacher.

Immunological age may be a risk factor for severe progression

Of particular interest to the researchers was that in patients with a severe disease progression, the T cells recognize SARS-CoV-2 just as badly as the "pre-existing" memory T cells. "This could indicate that in the severe cases of COVID-19, these immune cells come from the badly binding pre-existing memory T cells," said Bacher. "This could provide a simple explanation for why older people have a higher risk of severe disease progression. They often also have a higher immunological age, and thus also a higher probability that the immune system makes use of these "incompetent" pre-existing memory cells," continued Bacher.

"Our research shows that previous common colds caused by coronaviruses do not offer efficient immune protection against SARS-CoV-2. In addition, it provides important indications that the immunological age may possibly promote the severe progression of COVID-19. Further studies are now needed to investigate a direct connection between immunological age and severe COVID-19, and analyze the influence of pre-existing memory cells on the immune reaction to SARS-CoV-2 in more detail," said Scheffold.