Millimetre-precision drug delivery to the brain

Method is set to enable treatment of psychiatric and neurological disorders and tumours with fewer side effects in the future.

Researchers at ETH Zurich have developed a method for concentrating and releasing drugs in the brain with pinpoint accuracy. This could make it possible in the future to deliver psychiatric and cancer drugs and other medications only to those regions of the brain where this is medically desirable.

If drugs can be targeted only to the pathological brain areas, their undesirable side effects can be eliminated (Symbolic image).

TheDigitalArtist, pixabay.com

Today, this is practically impossible – drugs travelling through the bloodstream reach the entire brain and body, which in some cases causes side effects. The new method is non-invasive, with precise drug delivery in the brain controlled from outside the head using ultrasound. Mehmet Fatih Yanik, Professor of Neurotechnology, and his team of scientists have published their findings in the journal Nature Communications.

In order to prevent a drug from acting on the entire brain and body, the new method involves special drug carriers that wrap the drugs in spherical lipid vesicles attached to gas-containing ultrasound-sensitive microbubbles. These are injected into the bloodstream, which transports them to the brain. Next, the scientists use focused ultrasound waves in a two-stage process. Focused ultrasound is already employed in oncology to destroy cancer tissue at precisely defined points in the body. In the new invention, however, the scientists work with much lower energy levels, which do not damage the tissue.

Trapping drugs with sound waves

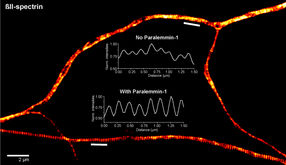

In the first step, the scientists use low energy ultrasound waves to cause the drug carriers to aggregate at the desired site within the brain. “What we’re doing is using pulses of ultrasound essentially to create a virtual cage from sound waves around the desired site. As the blood circulates, it flushes the drug carriers through the whole brain. But the ones that enter the cage can’t get back out,” Yanik explains.

In the second step, the researchers use a higher level of ultrasound energy to get the drug carriers to vibrate at this site. Shear forces destroy the lipid membranes around the drugs, releasing the drugs to be absorbed by the nerve tissue present at the site.

The researchers have demonstrated the effectiveness of the new method in experiments on rats. First they encapsulated a neuro-inhibitory drug in the drug carriers. Then, using the new technique, they successfully blocked a specific neural network connecting two areas of the brain. The scientists were able to show in the experiments that only this one particular part of the neuronal network was blocked and that the drug did not act on the entire brain.

More efficient drug delivery

“Because our method aggregates drugs at the site in the brain where their effect is desired, we don’t need nearly as high a dose,” Yanik says. In their experiments on rats, for instance, the quantity of drug that they used was 1,300 times smaller than the typical dose needed.

Other research groups have already tried to use focused ultrasound to enhance delivery of drugs to specific regions of the brain. However, these approaches couldn’t trap and concentrate drugs locally, and they instead relied on causing local damage to the blood vessel cells in order to increase the drug transport from the blood to the nerve tissue with potentially long-term detrimental consequences. “In our approach, the physiological barrier between the bloodstream and nervous tissue remains intact,” Yanik says.

The scientists are currently testing the effectiveness of their method in animal models of mental illness, for example to reduce anxiety, of neurological disorders and to target lethal brain tumours that are surgically inaccessible. Once its effectiveness and advantages have been confirmed in animals will researchers be able to advance application of the method to alleviate suffering in humans.

Original publication

Ozdas MS, Shah AS, Johnson PM, Patel N, Marks M, Yasar TB, Stalder U, Bigler L, von der Behrens W, Sirsi SR, Yanik MF; "Non-invasive molecularly-specific millimeterresolution manipulation of brain circuits by ultrasound-mediated aggregation and uncaging of drug carriers"; Nature Communications; 1. Oktober 2020