Less “Sticky” Cells Become More Cancerous

Researchers investigated mobility of cancer cells

In cooperation with colleagues from Germany, Italy and the Netherlands, researchers at Leipzig University have investigated the structure of tumour tissue and the behaviour of tumour cells in detail, gaining important insights that could improve cancer diagnosis and therapy in the future. They found out that during tumour development the way cells move can change from coordinated and collective to individual and chaotic behaviour. They have just published their research findings in the journal “Nature Cell Biology”.

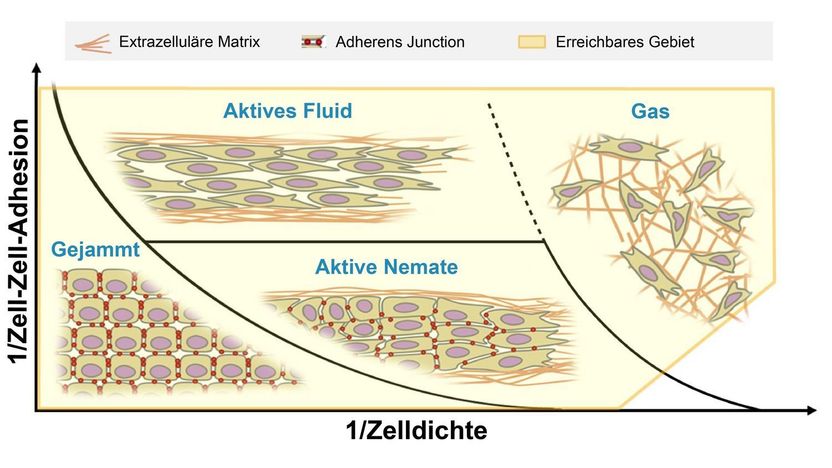

Schematic representation of different types of movement of tumour tissue in the extracellular matrix.

Peter Friedl, Stefano Zappen, Andreas Deutsch, Josef A. Käs, Jürgen Lippoldt

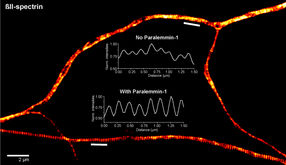

The paper was supervised by tumour biologist Professor Peter Friedl of Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, in cooperation with the research groups headed by Professor Josef A. Käs (Leipzig University), Professor Andreas Deutsch (TU Dresden) and Professor Stefano Zapperi (University of Milan). The scientists studied biological changes that cells usually undergo as cancer develops. The most typical of these is the degradation of the epithelial adhesion molecule E-cadherin. In other words: the cells become less “sticky”. The researchers showed that this degradation is accompanied by a change in the type of mobility in the tissue. Cells that are more cancerous can move freely past others of their kind, while the epithelial cells are “trapped” by their neighbours.

“It has long been assumed that the reduction in cell ‘stickiness’ during tumour development increases the mobility of these cancer cells. Our international team was able to confirm this fundamental assumption and show that a dense environment can still hold cancer cells back,” said Professor Käs. In his view, it is clear that tumour invasion is strongly influenced by the local environment: cells acting individually can also move in groups if this reduces the resistance of the surrounding tissue. Both types of cell movement led to metastases in the researchers’ experiments.

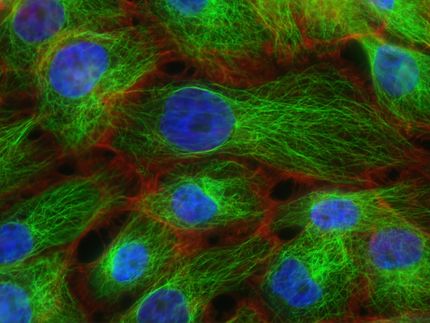

Most cancers are carcinomas that develop from epithelial tissue that covers and separates the organs. Its functions include protection and support. Immobile under healthy conditions, cells in this epithelium are a standard example in new research into “cell jamming”, a field which is currently developing rapidly. This immobility is explained by the fact that the cells are in each other’s way – similar to cars in a traffic jam or individual grains in a pile of sand. And to metastasise, cancer cells need the ability to move through the body. Their phenotype changes during tumour development, moving away from epithelial behaviour.

In experiments on tumour cells taken from patients, the researchers found that cancer cells spread in different ways in different environments: cells with an epithelial phenotype remained in a closed network, in which their movements were coordinated and collective. Less “sticky” cells in turn became more cancerous, with their cohesion reducing and movements growing more fluid. Individual, less “sticky” cells separated into the surrounding tissue. “This only happens if this tissue is not too dense. This movement is not coordinated, in step, as it would be in cells with an epithelial phenotype, but random and not coordinated with adjacent cells,” said doctoral researcher Jürgen Lippoldt from Leipzig University. “In order to turn this understanding into an advantage for cancer patients, further research is needed to find out which migration method can lead to metastases under which circumstances.”