"Love hormone" oxytocin could be used to treat Alzheimer's

Scientists discover for the first time that oxytocin could be a potential new therapeutic option for cognitive disorders

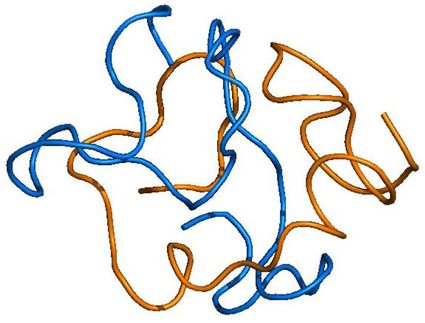

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive disorder in which the nerve cells (neurons) in a person's brain and the connections among them degenerate slowly, causing severe memory loss, intellectual deficiencies, and deterioration in motor skills and communication. One of the main causes of Alzheimer's is the accumulation of a protein called amyloid β (Aβ) in clusters around neurons in the brain, which hampers their activity and triggers their degeneration. Studies in animal models have found that increasing the aggregation of Aβ in the hippocampus--the brain's main learning and memory center--causes a decline in the signal transmission potential of the neurons therein. This degeneration affects a specific trait of the neurons, called "synaptic plasticity," which is the ability of synapses (the site of signal exchange between neurons) to adapt to an increase or decrease in signaling activity over time. Synaptic plasticity is crucial to the development of learning and cognitive functions in the hippocampus. Thus, Aβ and its role in causing cognitive memory and deficits have been the focus of most research aimed at finding treatments for Alzheimer's.

Oxytocin, the hormone that induce feelings of love and well-being within us, are found to reverse some of the damage caused by amyloid plaques in the learning and memory center of the brain in an animal model of Alzheimer's

Tokyo University of Science

Now, advancing this research effort, a team of scientists from Japan, led by Professor Akiyoshi Saitoh from the Tokyo University of Science, has looked at oxytocin, a hormone conventionally known for its role in the female reproductive system and in inducing the feelings of love and well-being. "Oxytocin was recently found to be involved in regulating learning and memory performance, but so far, no previous study deals with the effect of oxytocin on Aβ-induced cognitive impairment," Prof Saitoh says. Realizing this, Prof Saitoh's group set out to connect the dots. Their findings are published in Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communication.

Prof Saitoh and team first perfused slices of the mouse hippocampus with Aβ to confirm that Aβ causes the signaling abilities of neurons in the slices to decline or--in other words--impairs their synaptic plasticity. Upon additional perfusion with oxytocin, however, the signaling abilities increased, suggesting that oxytocin can reverse the impairment of synaptic plasticity that Aβ causes.

To find out how oxytocin achieves this, they conducted a further series of experiments. In a normal brain, oxytocin acts by binding with special structures in the membranes of brain cells, called oxytocin receptors. The scientists artificially "blocked" these receptors in the mouse hippocampus slices to see if oxytocin could reverse Aβ-induced impairment of synaptic plasticity without binding to these receptors. Expectedly, when the receptors were blocked, oxytocin could not reverse the effect of Aβ, which shows that these receptors are essential for oxytocin to act.

Oxytocin is known to facilitate certain cellular chemical activities that are important in strengthening neuronal signaling potential and formation of memories, such as influx of calcium ions. Previous studies have suspected that Aβ suppresses some of these chemical activities. When the scientists artificially blocked these chemical activities, they found that addition of oxytocin addition to the hippocampal slices did not reverse the damage to synaptic plasticity caused by Aβ. Additionally, they found that oxytocin itself does not have any effect on synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus, but it is somehow able to reverse the ill-effects of Aβ.

Prof Saitoh remarks, "This is the first study in the world that has shown that oxytocin can reverse Aβ-induced impairments in the mouse hippocampus." This is only a first step and further research remains to be conducted in vivo in animal models and then humans before sufficient knowledge can be gathered to reposition oxytocin into a drug for Alzheimer's. But, Prof Saitoh remains hopeful. He concludes, "At present, there are no sufficiently satisfactory drugs to treat dementia, and new therapies with novel mechanisms of action are desired. Our study puts forth the interesting possibility that oxytocin could be a novel therapeutic modality for the treatment of memory loss associated with cognitive disorders such as Alzheimer's disease. We expect that our findings will open up a new pathway to the creation of new drugs for the treatment of dementia caused by Alzheimer's disease."