The tricks of the immune system

How the T-cell response changes in chronic virus infections

Advertisement

More than half of the world's population is infected with the cytomegalovirus. The majority of people don't even notice the infection, since their immune systems keep the virus in check. Groups of T cells with a variety of virus-specific receptors play a key role in this process. Now researchers at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) have analyzed their interactions in detail for the first time. The results could be useful for future therapies against infections and cancer.

Symbolic image

succo, pixabay.com, CC0

"The COVID-19 pandemic clearly demonstrates the importance of understanding how the immune system reacts to virus infections," says Dr. Kilian Schober. Together with an interdisciplinary team of researchers from Medicine, Biology and Bioinformatics, he is investigating how important agents in the body's immune system known as T lymphocytes or T cells react when a cytomegalovirus invades the organism and how the immune response changes when the infection becomes chronic.

The team was able to show that the T cell response is a dynamic process and published their findings in the journal Nature Immunology. Different T cells with different receptors are especially active in various phases of the virus infection. "The discovery of this change over time was a big surprise to us," says Schober, the lead author of the study. Until now scientists assumed that after an infection primarily those defense cells multiplied that are especially good at docking onto the cell structures impacted by the virus. As a result it was assumed that in a chronic infection the number of these highly specialized "killer" cells remained permanently increased. But the new research results show a reversal in selection: The longer the infection lasts, the lower the average binding strength of the T cells.

The secret of reverse selection

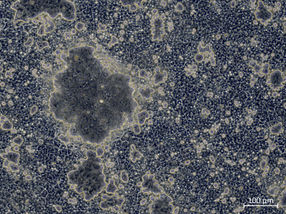

In order to monitor the T cell response over the course of an infection, the team led by Prof. Dirk Busch, director of the TUM Institute for Medical Microbiology, Immunology and Hygiene, analyzed blood samples from people who carry the cytomegalovirus. This very widespread virus, from the family of herpes viruses, is found in more than half the world's population. The majority of those infected have no symptoms, but the virus can trigger infections of the lungs or the liver in patients with weaker immune systems. In the majority of cases the time of infection in humans is unknown and remains unnoticed for several years. Therefore, the team also conducted laboratory investigations of the blood of mice infected with the cytomegalovirus where the date of the initial infection was known.

The team used a procedure it developed itself to isolate and analyze the defense cells. Every person has millions of different T cells, each with an individual protein complex on its surface. The structure of this T cell receptor (TCR) determines which virus structures it can dock onto and how firmly it will adhere.

The result of the complex investigation: Immediately after an infection with cytomegalovirus, T cells with strong bonding receptors dominate. After some time however almost exclusively the weaker-bonding receptors are found in the blood.

Prof. Busch emphasizes the fact that we can only speculate about the possible benefits of this reverse selection: "We assume that the modified immune reaction protects the organism from an excessive immune system reaction." He adds that a long-term secretion of cytokines by T cells with high binding affinity can trigger strong inflammation and thus harmful side-effects.

Important findings for infection and cancer therapies

"These findings are particularly exciting in the context of therapeutic application. T cells have been used successfully as 'living drugs' for over 25 years. Our findings suggest that in cases of chronic immune responses, T cells with weaker binding receptors are longer-lived," says Prof. Busch, adding that in the future the results could help improve T cell therapies used to fight infectious diseases and tumors.