Chimpanzee and Gorilla Genome May Help Better Understand Human Tumors

A new article looks at cancer from the point of view of evolution

A new study by researchers at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE), a joint centre of the UPF and the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), shows that, surprisingly, the distribution of mutations in human tumours is more similar to that of chimpanzees and gorillas than to that of humans.

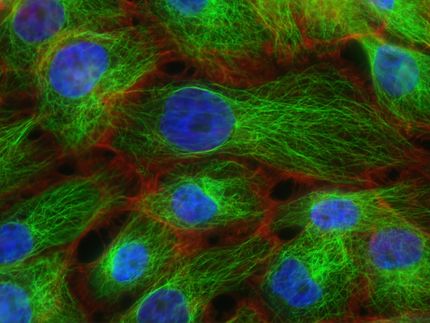

Pixabay

The article, in which cancer is analysed from the point of view of evolution, is published in Nature Communications. It has been led by Arcadi Navarro and David Juan and the researchers Txema Heredia-Genestar and Tomàs Marquès-Bonet have participated.

Mutations are changes that occur in the DNA. They are not distributed evenly across the genome, with some regions accumulating more and others less. Although mutations are common in healthy human cells, it is the cancer cells that show the most genetic changes. During the development of cancer, tumors accumulate a large number of mutations very quickly. However, previous studies have shown that, surprisingly, tumors accumulate mutations in very different regions of the genome than those normally seen in humans.

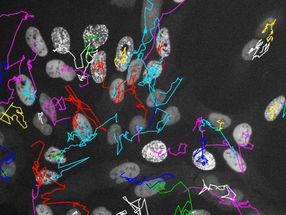

Now, using data from the PanCancer project, an IBE research team has compared the regions of the genome that accumulate more and fewer mutations in tumour processes, in the recent history of human populations, and in the history of other primates. The results of this new study show that the distribution of mutations in tumours is more similar to that in chimpanzees and gorillas than in humans.

"Until now it was thought that the genetic differences we found when we compared tumors and healthy humans might be caused by the 'abnormal' way tumors accumulate mutations. In fact, we know that tumors accumulate a large number of mutations very quickly and that many of their genome repair mechanisms do not work well," says Txema Heredia-Genestar, first author of the study and recently a doctorate student at IBE. "But now, we have discovered that a large part of these genetic differences have to do with our evolutionary history.

The distribution of mutations in humans, biased by population events

When you sequence a person's genome, you see that they have a small number of new mutations -- about 60 -- relative to their parents, the ones their parents have relative to their grandparents, and so on with previous generations. So in one person you can see about three million mutations which represent the evolutionary history of mutations accumulated over hundreds of thousands of years. Of these, a few are recent and most are very old.

In contrast, when the mutations of a tumour are analysed, only the mutations that have taken place during the tumour process are seen, as the analysis does not take into account information on the population history.

"We have seen that the distribution of the mutations in the human genome is biased due to human evolutionary history", details Heredia-Genestar. The way a tumor accumulates mutations is the same way a human cell accumulates mutations. "But we don't see this in the human genome because we have had such a complicated history that has caused our mutation distributions to change, and this has erased the signals we should have," he adds.

Throughout history, the human population has suffered drastic declines and has even come close to extinction repeatedly. This phenomenon is known as a bottleneck, and it means that as a species humans have very little diversity and fewer mutations: they are very similar to each other. In fact, chimpanzees have four times more diversity at the genetic level than humans.

Therefore, the global way of a cell to accumulate mutations can be seen in chimpanzees because they have not had these population events. The study concludes that to understand how mutations accumulate in human cells, which is relevant to the study of tumours, it is more useful to look at how they accumulate in other primates rather than studying them in human populations, which have a signal destroyed by population events.

"Cancers, like chimpanzees and gorillas, only show the complete mutation landscape of a normal human cell. It is we humans with a distant turbulent past who show a distorted distribution of mutations," adds Arcadi Navarro, ICREA research professor at IBE, professor at UPF and co-leader of the study.

The study points out that the conservation and study of great apes could be very relevant to the understanding of human health. David Juan, co-leader of the study, concludes that "in the particular case of tumor development, other primates have proven to be a better model for understanding how tumors develop at the genetic level than humans themselves. In the future, our close relatives may shed light on the understanding of many other human diseases".

Note: This article has been translated using a computer system without human intervention. LUMITOS offers these automatic translations to present a wider range of current news. Since this article has been translated with automatic translation, it is possible that it contains errors in vocabulary, syntax or grammar. The original article in Spanish can be found here.