Interorganellar signals regulate longevity

Lysosome to mitochondria communication

Advertisement

As people get older, they often feel less energetic, mobile or active. This may be due in part to a decline in mitochondria, the tiny powerhouses inside of our cells, which provide energy and regulate metabolism. In fact, mitochondria decline with age not only in humans, but in many species. Why they do so is not well understood. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Biology of Ageing in Cologne set out to understand how mitochondrial function is diminished with age and to find factors that prevent this process. They found that communication between mitochondria and other parts of the cell plays a key role.

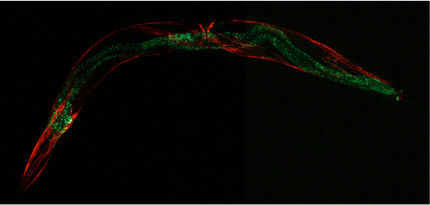

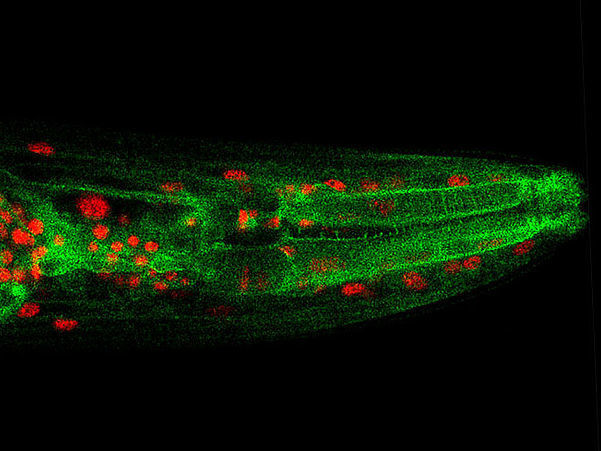

Microscopy image of a C. elegans worm, where red marks the nucleus, where NFYB-1 is present, and green marks lysosomes.

© Raymond Laboy

For their studies, the scientists used the simple roundworm, Caenorhabditis elegans, an important model system for ageing research. Over half the genes of this animal are similar to those found in humans, and their mitochondria also decline with age. From their research, the scientists found a nuclear protein called NFYB-1 that switches on and off genes affecting mitochondrial activity, and which itself goes down during ageing. In mutant worms lacking this protein, mitochondria don’t work as well and worms don’t live as long.

Unexpectedly, the scientists discovered that NFYB-1 steers the activity of mitochondria through another part of the cell called the lysosome, a place where basic molecules are broken down and recycled as nutrients. “We think the lysosome talks with the mitochondria through special fats called cardiolipins and ceramides, which are essential to mitochondrial activity,” says Max Planck Director, Adam Antebi, whose laboratory spearheaded the study. Remarkably, simply feeding the NFYB-1 mutant worms cardiolipin restored mitochondrial function and worm health in these strains. Because cardiolipins and ceramides are also essential for human mitochondria, this may mean human health and ageing can be improved by understanding on how such molecules facilitate communication between different parts of the cell.