Division of labour on the surface of bacteria

Heat-loving bacteria use various tiny surface hairs for movement and DNA reception

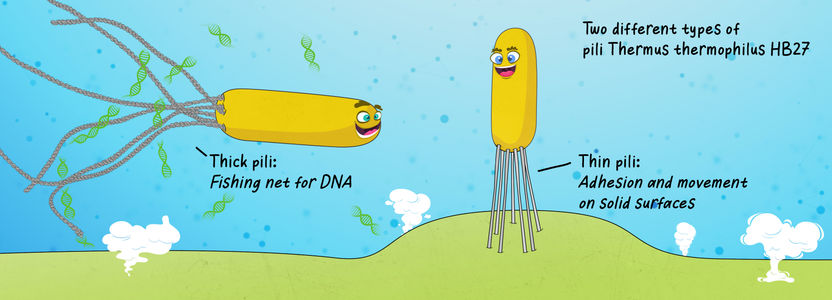

bacteria of the species Thermus thermophilus possess two types of extensions on their surface (pili) for the purpose of motion and for capturing and absorbing DNA from their environment. This has been discovered by researchers at Goethe University together with researchers in Great Britain. The discovery of the motion pilus helps to better understand the functionality of the DNA-capturing pilus functions.

Bacteria of the species Thermus thermophilus possess different tiny hairs (pili) which are used either to capture DNA or for motion. This has been discovered by scientists at Goethe University Frankfurt and the University of Exeter.

aduka, Agency Frankfurt am Main(www.aduka.de) für Goethe-Universität Frankfurt.

The bacteria Thermus thermophilus likes it hot. It was first discovered in the hot springs at Izu in Japan, where it thrives at an optimal temperature of about 65 degrees Celsius. Like all bacteria, Thermus thermophilus has developed mechanisms to adjust to changing environmental conditions. The bacteria changes its genetic material by exchanging DNA with other bacteria, or absorbing DNA fragments from its environment. These might come from dead bacteria cells, plants or animals. The bacteria incorporate the DNA fragments into their genetic material and keep it if the DNA proves useful.

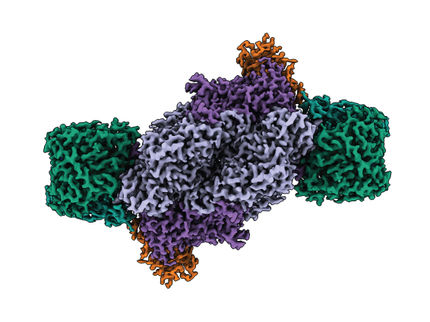

Microbiologists at Goethe University led by Professor Beate Averhoff from the Molecular Microbiology & Bioenergetics of the Department of Molecular Biosciences together with a team of scientists led by Dr Vicky Gold from the “Living Systems” Institute of the University of Exeter in Great Britain have now studied the tiny hairs (called pili) on the surface of the Thermus bacteria. The scientists discovered that there are two types of pili with different functions. High-resolution electron microscope images from Great Britain allow thick and thin pili to be distinguished, and the Frankfurt scientists used biochemical and molecular biological methods to demonstrate that the thick pili are for DNA capture, and the thin pili for moving on surfaces.

“We want to find out exactly how Thermus thermophilus absorbs DNA from its environment using its pili, as the precise mechanism is unknown,” explains Professor Beate Averhoff from the Institute for Molecular Biosciences at Goethe University. “Through our most recent investigations we have learned that Thermus bacteria have distinct pili for motion. Therefore, the thick pili possibly serve the purpose of DNA absorption, which demonstrates how important this process is for the bacteria. In our structure analyses we also found an area on the thick pili where DNA could bind.”

The interplay of electron microscopy and molecular biology also allowed the scientists to better understand the mechanics of the pili. For both motion and DNA absorption, pili have to be dynamic, i.e., able to be extended and retracted. “For the first time, the high resolution structure of both pili gave us insights not only into the structure of the pili, but also into the dynamics,” Averhoff explains.

Since pili are widespread and in pathogenic bacteria are also responsible for attaching to the host, this may lead to new points of attack for preventing infectious processes.