Blood stem cells boost immunity by keeping a record of previous infections

A newly discovered memory in our bones

A Franco-German research team led by Prof. Michael Sieweke, from the Center for Regenerative Therapies TU Dresden (CRTD) and the Center of Immunology of Marseille Luminy (CNRS, INSERM, Aix-Marseille University), today uncovered a surprising property of blood stem cells: not only do they ensure the continuous renewal of blood cells and contribute to the immune response triggered by an infection, but they can also remember previous infectious encounters to drive a more rapid and more efficient immune response in the future. These findings should have a significant impact on future vaccination strategies and pave the way for new treatments of an underperforming or over-reacting immune system.

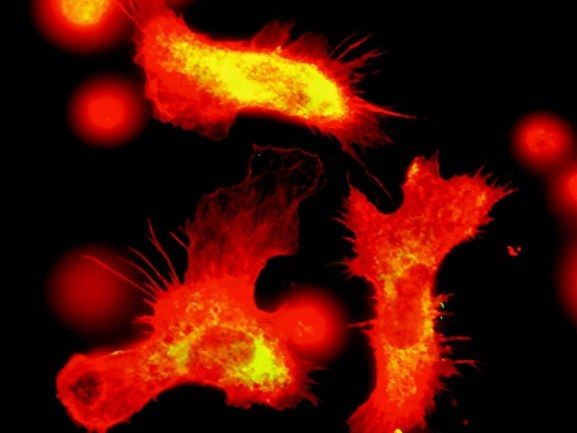

Immune cells by fluorescence microscopy: Blood stem cells remember a previous attack and produce more immune cells like these macrophages to fight a new infection

© Sieweke lab / CIML

Stem cells in our bodies act as reservoirs of cells that divide to produce new stem cells, as well as a myriad of different types of specialized cells, required to secure tissue renewal and function. Commonly called “blood stem cells”, the hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) are nestled in the bone marrow, the soft tissue that is in the center of large bones such as the hips or thighs. Their role is to renew the repertoire of blood cells, including cells of the immune system which are crucial to fight infections and other diseases.

Until a decade ago, the dogma was that HSCs were unspecialized cells, blind to external signals such as infections. Only their specialized daughter cells would sense these signals and activate an immune response. But work from Prof. Michael Sieweke’s laboratory and others over the past years has proven this dogma wrong and shown that HSCs can actually sense external factors to specifically produce subtypes of immune cells “on demand” to fight an infection. Beyond their role in an emergency immune response, the question remained as to the function of HSCs in responding to repeated infectious episodes. The immune system is known to have a memory that allows it to better respond to returning infectious agents. The present study now establishes a central role for blood stem cells in this memory.

“We discovered that HSCs could drive a more rapid and efficient immune response if they had previously been exposed to LPS, a bacterial molecule that mimics infection”, said Dr. Sandrine Sarrazin, Inserm researcher and senior-author of the publication. Prof. Michael Sieweke, Humboldt Professor at TU Dresden, CNRS Research Director and last author of the publication, explained how they found the memory was stored within the cells: “The first exposure to LPS causes marks to be deposited on the DNA of the stem cells, right around genes that are important for an immune response. Much like bookmarks, the marks on the DNA ensure that these genes are easily found, accessible and activated for a rapid response if a second infection by a similar agent was to come.”

The authors further explored how the memory was inscribed on the DNA, and found C/EBPb to be the major actor, describing a new function for this factor, which is also important for emergency immune responses. Together, these findings should lead to improvements in tuning the immune system or better vaccination strategies.

“The ability of the immune system to keep track of previous infections and respond more efficiently the second time they are encountered is the founding principle of vaccines. Now that we understand how blood stem cells book mark immune response circuits, we should be able to optimize immunization strategies to broaden the protection to infectious agents. It could also more generally lead to new ways to boost the immune response when it underperforms or turn it off when it overreacts”, concluded Prof. Michael Sieweke.