Brain-doping produced by your own body

Researchers have uncovered the mechanism by which Epo acts in nerve cells

Advertisement

erythropoietin, or Epo for short, is a notorious doping agent. It promotes the formation of red blood cells, leading thereby to enhanced physical performance - at least, that is what we have believed until now. However, as a growth factor, it also protects and regenerates nerve cells in the brain. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Experimental Medicine in Göttingen have now revealed how Epo achieves this effect. They have discovered that cognitive challenges trigger a slight oxygen deficit (termed ‘functional hypoxia’ by the researchers) in the brain’s nerve cells. This increases production of Epo and its receptors in the active nerve cells, stimulating neighbouring precursor cells to form new nerve cells and causing the nerve cells to connect to one another more effectively.

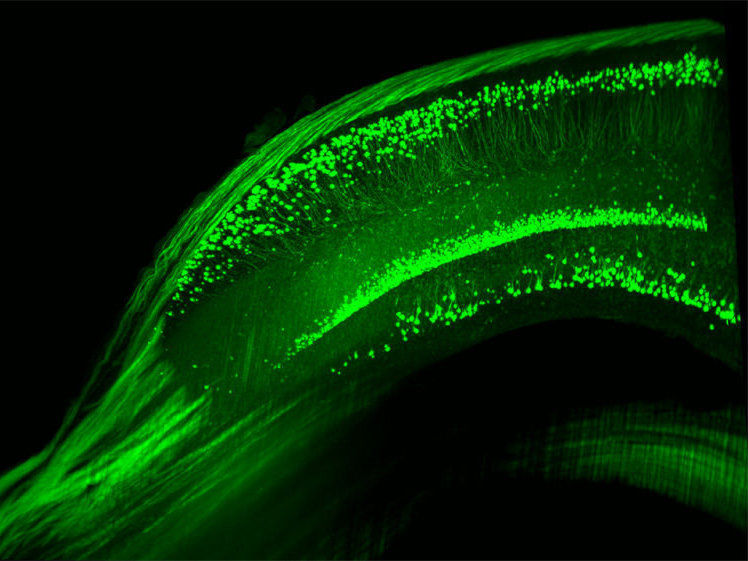

Cross section through the hippocampus of a mouse. After administration of erythropoietin, the animals have more nerve cells in this brain region that is central for learning and memory.

© MPI f. Psychiatry

The growth factor erythropoietin is among others responsible for stimulating the production of red blood cells. In anaemia patients it promotes blood formation. It is also a highly potent substance used for illegal performance enhancement in sports.

“Administering Epo improves regeneration after a stroke (termed ‘neuroprotection’ or ‘neurogeneration’), reducing damage in the brain. Patients with mental health disorders such as schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder or multiple sclerosis who have been treated with Epo have shown a significant improvement in cognitive performance,” says Hannelore Ehrenreich of the Max Planck Institute of Experimental Medicine. Along with her colleagues, she has spent many years researching the role played by Epo in the brain.

More neurons

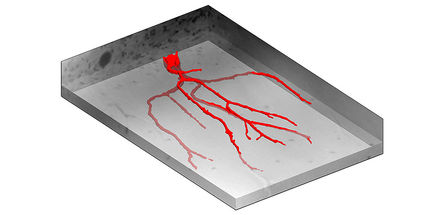

Ehrenreich and her team have been using mice in animal studies for a systematic investigation into which bodily mechanism lies at the root of Epo’s effect on enhanced brain performance. The results of her research indicate that in adult mice, there is a 20 percent increase in the formation of nerve cells in the pyramidal layer of the hippocampus - a brain region crucial for learning and memory - after the growth factor is administered. “The nerve cells also form better networks with other nerve cells, and do this more quickly, making them more efficient at exchanging signals”, says Ehrenreich.

The researchers gave the mice running wheels with irregularly-spaced spokes. “Running in these wheels requires the mice to learn complex sequences of movement that are particularly challenging for the brain,” explains Ehrenreich. The results demonstrate that the mice learn the movements required for the wheels more quickly after Epo treatment. The rodents also show significantly better endurance.

Higher oxygen requirements

It was important to the Göttingen researchers to understand the mechanisms behind these potent Epo effects. They wanted to track down the physiological significance of the Epo system in the brain. In a series of targeted experiments, they were able to prove that when learning complex motor tasks, nerve cells require more oxygen than is normally available to them. The resulting minor oxygen deficiency (relative hypoxia) triggers the signal for increased Epo production in the nerve cells. “This is a self-reinforcing process: Cognitive exertion leads to minor hypoxia, which we term ‘functional hypoxia’, which in turn stimulates the production of Epo and its receptors in the corresponding active nerve cells. Epo subsequently increases the activity of these nerve cells, induces the formation of new nerve cells from neighbouring precursor cells, and increases their complex interconnection, leading to a measurable improvement in cognitive performance in humans and mice,” explained Ehrenreich.

The self-reinforcing cycle of mental and cognitive challenge, activity-induced hypoxia and Epo production can be influenced in various ways: “Cognitive performance can be improved through consistent learning and mental training via Epo production in the stimulated nerve cells. A similar effect can be achieved in patients by administering additional Epo,” says Ehrenreich.