Unstable chromosomes can promote breast cancer

Altered chromosomes lead to treatment resistance

If chromosomes are unevenly distributed or otherwise altered during cell division, this normally damages the daughter cells and impairs their viability. Not in cancer cells, however, in which chromosome instability can actually confer a growth advantage under certain circumstances. Moreover, as scientists from the German Cancer Research Center have now demonstrated in mice, changes in the chromosomes can lead to breast cancer cells becoming resistant to treatment. The researchers have thus gained new insight into the mechanisms by which tumor cells circumvent the effect of treatment.

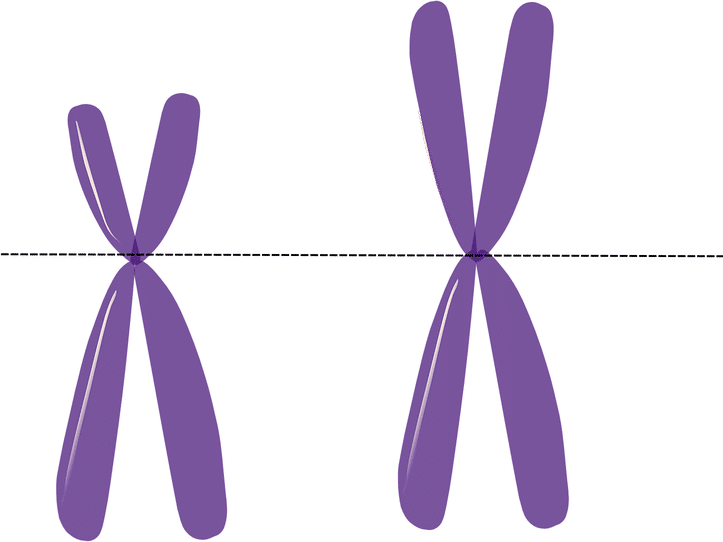

Unstable chromosomes can promote breast cancer

OpenClipart-Vectors, pixabay.com, CC0

In cell division, the chromosomes of the parent cell are normally divided equally between the two daughter cells. Errors in the structure or number of chromosomes during this process are referred to as chromosome instability. The consequences for the affected cells are severe: The wrong amounts of proteins are produced, the metabolism gets out of control, and the cells often eventually die by programmed cell death (apoptosis).

The situation is different in cancer cells. The abnormal number of chromosomes appears to provide a survival advantage. Chromosome instability is regarded as an indicator of an unfavorable course of disease in cancer and is also thought to be associated with treatment resistance. The mechanisms underlying this survival advantage were not previously clear, however.

"In fact, 90 percent of solid tumors and 75 percent of hematopoietic tumors have unevenly distributed chromosomes," explained Rocio Sotillo from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ). It is not necessarily whole chromosomes that are unevenly distributed. Segments of chromosomes can also get lost or be replicated.

Sotillo and her team have now demonstrated that chromosome instability itself can contribute to treatment resistance. To do so, the researchers resorted to various tricks in the field of molecular biology and bred mice in which the cancer-promoting gene KRAS can be specifically switched on – these animals thus develop breast cancer. In a second group of mice, the researchers activated another gene alongside KRAS, hence causing very pronounced chromosome instability.

In the next step, the DKFZ scientists switched off these genes again, which in principle simulates the effect of targeted treatment. In theory, cancer growth ought to have stopped in both groups. However, in more than 20 percent of the animals with chromosome instability, the tumors continued to grow – as they did in 6.6 percent of the mice in which only KRAS had previously been activated and chromosome instability had not been induced.

Moreover, when the researchers continued to observe the tumor growth, they discovered that the tumors in which the chromosomes had not been made unstable using the genetic trick showed anomalies too. The error rate in cell division was in fact just as high as in the animals in which chromosome instability had been induced right from the start.

More detailed genetic analysis of the resistant tumors showed that in half of the mice affected, certain chromosome segments had been replicated. During this process, an oncogene that is known to confer treatment resistance on many tumors was also replicated. The scientists treated the animals using a substance that targets the signaling protein for which this oncogene codes, and all the tumors did indeed reduce in size.

"The trick involving activating and then turning off genes allowed us to simulate targeted cancer treatment. Chromosome instability acts as a driver of genetic variability that confers a survival advantage through resistance development on the cancer cells under the treatment-related selection pressure," explained Sotillo, summarizing the results. "A few originally chromosomally stable tumor cells survive the treatment by acquiring chromosome instability at the same time. This increases their chances of developing treatment resistance."

The researchers still do not know what mechanisms of molecular biology underlie this effect and intend to devote future research to this issue. "We hope this will help us understand better how chromosome instability arises and hence resistance develops during targeted cancer treatment – and how we might be able to prevent it," Sotillo remarked.