How to mend a broken heart

Sticky proteins from sea mussels

If the heart muscle is damaged, repairing the constantly active organ is a challenge. Empa researchers are developing a novel tissue adhesive inspired by nature, which is able to repair lesions in muscle tissue. They have taken advantage of the incredible ability of marine mussels to adhere to any kind of surface.

Inspired by Mother Nature: Sea mussels resist the stormiest surf with ease. They hold on to the surface with protein threads. Empa researchers are using this property for a novel tissue glue for wound treatment.

melissamahon, pixabay.com, CC0

On wind- and wave-swept coasts, they adhere stoically to rocks, boats and jetties: sea mussels. With super powers that make Spiderman turn pale, the mussel's foot holds on to the surface, as its glands produce fine threads which, unlike spider silk, remain firm under water and yet highly elastic. Two proteins, mfp-3 and the particularly sulfurous mfp-6, are components of this sea silk. As structural proteins, they are especially interesting for biomedical research because of their fascinating mechanical properties and their biocompatibility.

Challenging conditions

Researchers from Empa's "Biomimetic Membranes and Textiles" lab in St. Gallen have made use of these properties. Claudio Toncelli's team was looking for a biocompatible tissue glue that would adhere to the beating heart while remaining elastic, even under the most challenging conditions. After all, if heart muscle tissue is damaged, for instance by a heart attack or a congenital disorder, the wounds must be able to heal, even though the muscle continues to contract.

"Actually, collagen is a suitable basis for a wound glue, a protein that is also found in human connective tissue and tendons," says Toncelli. For example, gelatin consists of cross-linked collagen that would be very attractive for a tissue adhesive. "The structure of gelatin already comes very close to some of the natural properties of human connective tissue," he adds. However, the hydrocolloid is not stable at body temperature, but liquefies. So in order to develop an adhesive material that can securely connect wounded areas on internal organs, the researchers had to find a way to incorporate additional properties into gelatin.

Under pressure

"The muscular foot of mussels excretes strongly adhesive threads, with which the mussel can adhere to all kinds of surfaces in water," explains Toncelli. In this sea silk, several proteins interact tightly. Inspired by nature's solution for dealing with turbulent forces under water, the researchers equipped gelatin biopolymers with functional chemical units similar to those of the sea silk proteins mfp-3 and mfp-6. As soon as the gelatin sea silk gel makes contact with tissue, the structural proteins cross-link with each other and ensure a stable connection between the wound surfaces.

The researchers have already investigated how well the novel hydrogel actually adheres in lab experiments that are usually used to define technical standards for so-called bursting strength. "The tissue adhesive can resist a pressure equivalent to human blood pressure," says Empa researcher Kongchang Wei. The scientists were also able to confirm the outstanding tissue compatibility of the new adhesive in cell culture experiments. They are now trying hard to advance the clinical application of the "mussel glue".

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Computer simulation of protein malfunction related to Alzheimer's disease

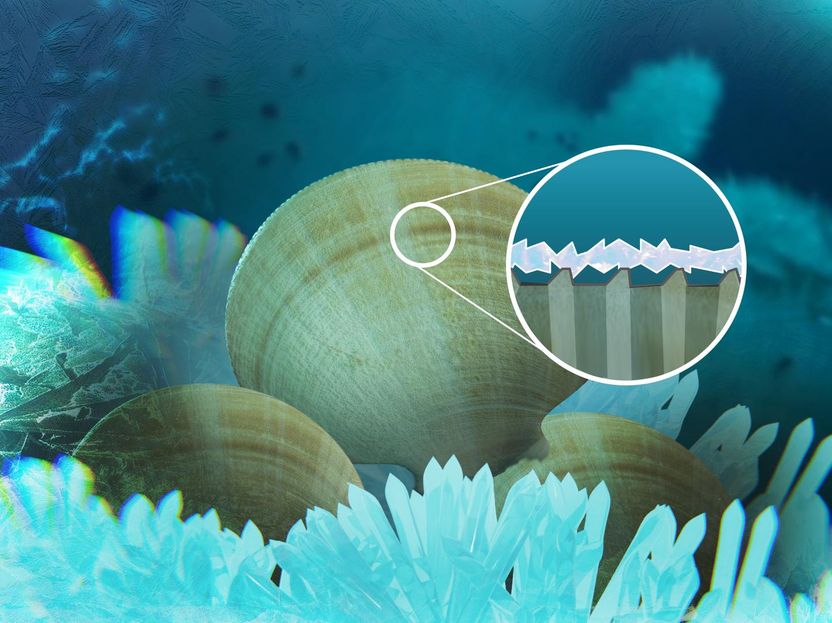

Ice-free in icy worlds: Special shell protects scallop from ice build-up - Airplane wings that don't ice up or solar cells that generate electricity even in winter - ice-free surfaces are important for many applications

Genes newly linked to longer human lifespan - A group of genes that play an essential role in building components of our cells can also impact human lifespan

Justin_Keating

Stäubli Tec-Systems GmbH Robotics - Bayreuth, Germany

Merck expands biotech capacities - Swiss facility in Aubonne grows

Joseph_W._Alexander

CVS_Caremark_Corporation

BASF and CSM announce joint production development of biobased Succinic Acid