Social control among immune cells improves defence against infections

This mechanism could improve immune therapies for cancer

A simple mechanism, previously known from bacteria, ensures that the immune system strikes a balance between the rapid expansion of immune cells and the prevention of an excessive self-damaging reaction after an infection. This has now been deciphered by scientists at the University of Freiburg - Medical Center (Germany) and colleagues from the Netherlands and Great Britain. An infection quickly activates T-cells, which leads to their proliferation. The research team has now shown that these cells are able to perceive each other and - based on their density – jointly determine whether or not they should continue to proliferate. The newly discovered mechanism could also help to improve cancer immunotherapies.

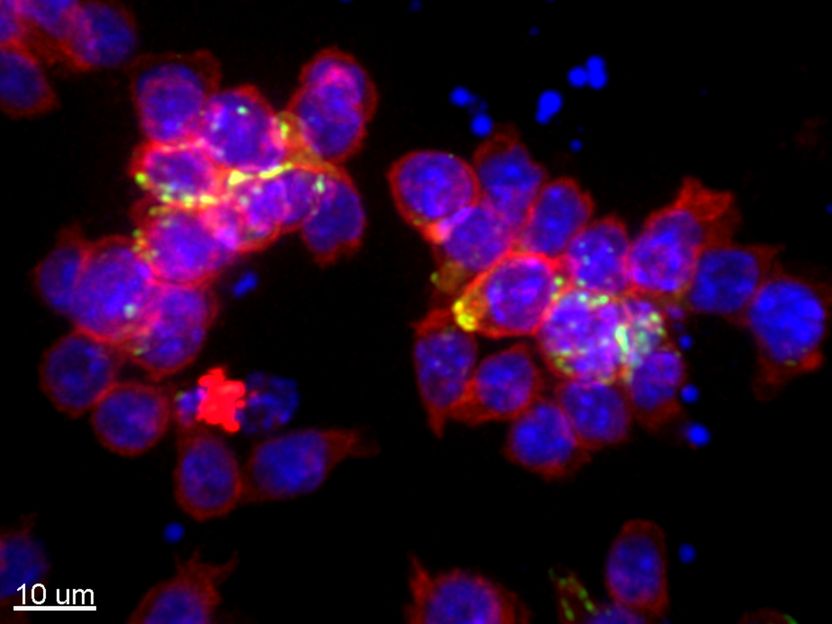

This image depicts T cells interacting with each other. Cell surfaces are labeled in red, cell nuclei in blue and receptors mediating communication in green.

Immunity Journal

Cooperation among immune cells

"We showed that these immune cells perceive and regulate each other. The immune cells act as a team and not as autonomously acting individualists," said Dr. Jan Rohr, head of the study and scientist at the Centre for Immunodeficiency (CCI) at the University of Freiburg - Medical Center. "This principle of density control of immune cells is simple and very effective. This makes it reliable and at the same time hopefully accessible for therapeutic approaches," said Rohr. At low density, the T-cells support each other in their proliferation. As soon as a threshold value of cell density is reached, the mutual support turns into mutual inhibition, which prevents further cell proliferation. This mechanism leads to the efficient amplification of initially weak immune reactions, but is also able to prevent excessive and potentially dangerous immune reactions.

Immunotherapies could become even more effective

This finding casts a new light on certain cancer immunotherapies. Tumors protect themselves by suppressing the immune system. To circumvent this, therapies have been developed in which T-cells are taken from patients, strengthened and expanded in the laboratory, and finally returned to the patient. For these therapies usually high cell counts are administered to make the therapy particularly effective. "It is possible that the immune cells switch off each other if they are administered at high numbers. A repeated administration of lower numbers of immune cells may fight the tumour cells more effectively. ," says Rohr. The extent to which this might help to improve current immunotherapies will have to be investigated in further studies.

In their study, the scientists investigated immune cells in the laboratory using microscopic time-lapse imaging and genetic analyses. The mechanisms found were then used by researchers at the University of Leiden, Netherlands, to develop a mathematical model of cell-cell interactions. Finally, the mechanisms found were tested in animal models. "These different research approaches complemented and supported each other very well," said the project leader from the University of Freiburg - Medical Center.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.