New evidence in plants shows microRNA can move

Advertisement

Ever since tiny bits of genetic material known as microRNA were first characterized in the early 1990s, scientists have been discovering just how important they are to regulating the activity of genes within cells. A new study now shows that microRNAs don't just control the activity of genes within a given cell, they also can move from one cell to another to send signals that influence gene expression on a broader scale.

Researchers at the Duke Institute for Genome Sciences & Policy (IGSP), in collaboration with groups at the Universities of Helsinki and Uppsala and the Boyce Thompson Institute for Plant Research at Cornell University, made the discovery while working out the intricate details of plant root development in Arabidopsis, a highly-studied mustard plant. Although they still don't know exactly how the microRNAs travel, it appears that this mobility allows them to play an important developmental role in sharpening the boundaries that define one plant tissue from another.

"To our knowledge, this is the first solid evidence that microRNAs can move from one cell to another," said Philip Benfey, director of the Duke IGSP Center for Systems Biology.

The findings, which appear in Nature, add microRNA to the list of mobile molecules, including hormones, proteins and other forms of small RNA, that allow for essential communication between cells in the process of organ development. They also add a new element to the already complex interplay in Arabidopsis roots between two proteins, known as Scarecrow and Short-root, that Benfey's team had described in earlier work. Those proteins interact and restrain one another to allow the assembly of a waterproofing layer of cells that ultimately enables plants to control precisely how much water and nutrients they take in.

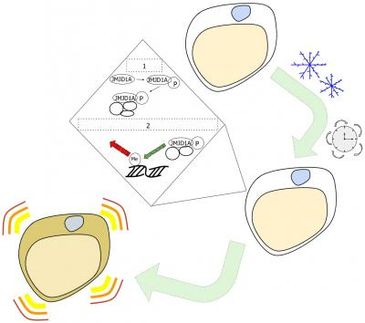

The researchers now show that Short-root moves from cells in the plant's inner vasculature out into the waterproofing endodermis that surrounds it to activate Scarecrow. Together, those two transcription factors (genes that control other genes) activate microRNAs, known as MIR165a and 166b. Those microRNAs then head back toward the vascular cells, meeting and degrading another transcription factor (called Phabulosa) as well as other regulatory factors along the way.

"Dr. Benfey and his colleagues have shown how two modes of gene regulation work together across cellular borders to ensure the proper patterning of plant root tissues," said Susan Haynes of the NIH's National Institute of General Medical Sciences, which partially funded the study. "This study provides important insight into how cells communicate positional information to orchestrate the complex process of tissue and organ development."

"Now we know that microRNAs can and do move to form gradients in the context of plant development," Benfey added. "It adds a new dimension to gene regulation."

According to Benfey, history suggests this kind of two-way communication involving microRNAs in the developing root is likely to be a more general phenomenon. "Just about everything in biology that once seemed particular sooner or later proves to be more general," he said.

He said there's also reason to think that the specific regulatory interactions they've uncovered were key in the evolutionary transition from single-celled algae to land plants.

"Formation of vascular tissue with a surrounding endodermal layer that acts as waterproofing was a key milestone in the evolution of land plants," Benfey said. "Without a tube to conduct water, you can't grow a tree or a sunflower."

Key collaborators on the study include Yrjo Helariutta of the University of Helsinki; Ji-Young Lee of the Boyce Thompson Institute and Annelie Carlsbecker of Uppsala University.