Obesity, heart disease or diabetes could be transmissible

A revolutionary hypothesis

Diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer or certain lung diseases are among the most common non-natural causes of death today and account for about 70 percent of deaths worldwide. They are defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as non-communicable because they are assumed to be caused by a combination of genetic, lifestyle and environmental factors and cannot be transmitted between humans. In a new research paper, a team from the "Humans & the Microbiome" program of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR), with the participation of Professor Thomas Bosch from Kiel University, is now questioning this view. The scientists provide convincing evidence that many diseases classified as non-communicable may possibly be passed on from person to person via the microbiome after all - and that the microbial colonisation of the human body, including bacteria, fungi and viruses, is centrally involved in the transmission. The researchers published the new hypothesis in the scientific journal Science.

Published the new hypothesis together with the researchers of the CIFAR "Humans & the Microbiome" program: Prof. Thomas Bosch from Kiel University.

© Christian Urban, Uni Kiel

A revolutionary hypothesis

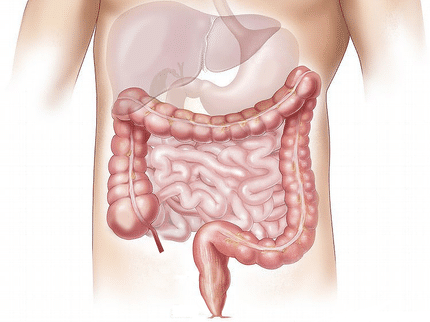

“If our hypothesis is proven correct, it will rewrite the entire book on public health”, says Brett Finlay, Professor of Microbiology at the University of British Columbia and head of the CIFAR program "Humans & the Microbiome". The scientists base their theory on making, for the first time, connections between three different already proven findings: First, they have been able to show that in a wide range of diseases, from obesity and inflammatory bowel disease to type-2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, the human microbiome shows significant changes compared to the healthy body. Secondly, they have provided ample evidence that such altered microbial compositions lead to the development of disease when transferred in laboratory experiments to an originally healthy model organism. If, for example, the intestinal microbiome is taken from an obese mouse and transferred to a healthy animal, the latter will also become overweight. Finally, they found numerous indications of a general natural transferability of the microbiome. “When you put those facts together, it points to the idea that many traditionally non-communicable diseases may be communicable after all”, says Finlay.

Researchers from Bosch's group at Kiel University have been able to prove the third aspect in particular. "If laboratory animals such as freshwater polyps are not kept individually, but rather were “co-housed” for a certain period of time in a common habitat, their microbiome first adapts to each other and then, as a result, also their phenotype," summarizes co-author Bosch, spokesperson of the Collaborative Research Center (CRC) 1182 "Origin and Function of Metaorganisms" at Kiel University. "We were able to show that the microbes pass directly from one individual to another. It is possible that this transmission of the microbiome also takes place during human coexistence, for example through intensive social contacts or in shared apartments," assumes Bosch.

Further research to validate the theory

The revolutionary new hypothesis of the CIFAR team is based on an explorative interdisciplinary exchange of the experts cooperating in the microbiome research program and their different scientific perspectives. Initiated only as a thought experiment, it quickly became clear that there are a number of clear indications from the various disciplines that make the new theory seem plausible – should it be correct, the implications for human health would obviously be extremely important. Nevertheless, the researchers stress that their hypothesis is daring and that many of the mechanisms involved are still unknown. “We still don't know in what cases transmission increases, or whether healthy outcomes can also be transmitted,” says co-author and CIFAR-Fellow Maria Gloria Dominguez-Bello, professor at Rutgers University in New Jersey. “We need more research to understand microbial transmission and its effects”, Dominguez-Bello continues.

However, there is no doubt today that there is a significant correlation between a disturbed microbiome and many diseases. Further research will show how the microbiome interacts with other influences, for example certain environmental conditions and genetic factors in the transmission of various diseases. "The new hypothesis makes it clear that we need to consider disturbances in the microbial colonization of the body as a cause of disease to a much greater extent than before, and that we also need to investigate the potential transmission pathways more closely," emphasizes Bosch. "In the coming years, this aspect will be one of the focal points of our work in our Metaorganism Collaborative Research Center," Bosch continued. The CRC 1182, which was launched at Kiel University in 2016, has been funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) for a further four years in a second funding phase since the beginning of the year.