First robust cell culture model for the hepatitis E virus

A mutation switches the turbo on during virus replication. This is a blessing for research.

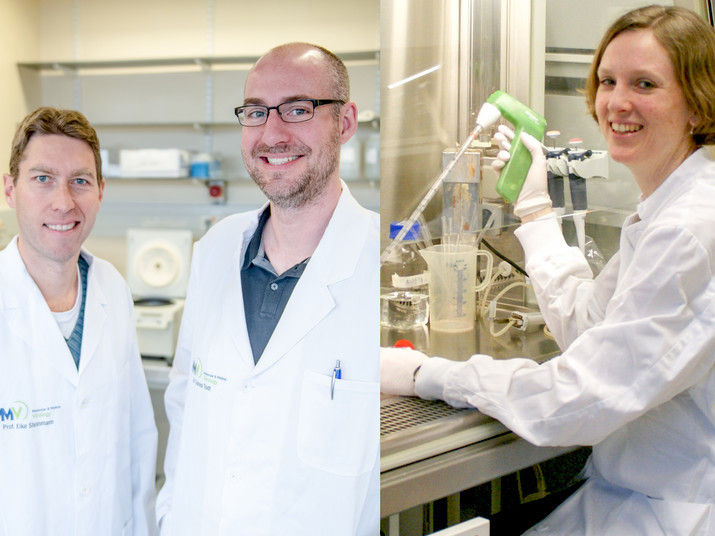

Eike Steinmann, Daniel Todt and Martina Friesland (from left) provide the scientific community with a cell model and comprehensive data on the hepatitis E virus.

© RUB, Marquard; Avista Wahid

Even though hepatitis E causes over three million infections and about 70,000 deaths each year, the virus has been little studied as yet. This may be about to change, because a research team from Bochum and Hanover has developed a robust and improved cell model of the pathogen. It produces about 100 times more infectious virus particles than previous models. “As a result, we are finally able to study the virus in depth,” says Professor Eike Steinmann, Head of the Department for Molecular & Medical Virology at Ruhr-Universität Bochum (RUB).

Mutation leads to increased proliferation

The lack of a robust cell culture model is one of the reasons why the hepatitis E virus (HEV) has been little investigated to date. “The number of infectious virus particles produced in previous models was simply too small to generate reproducible results,” explains Dr. Daniel Todt, author from Bochum.

In previous studies, the research team analysed virus populations resulting from genetic mutations of the virus in patients and identified a specific genetic change that leads to a significantly higher proliferation of the pathogen. The scientists inserted this mutation into the previously used cell lines and were thus able to increase the production of new virus particles by a factor of five to ten.

In their current article, they optimised the cell culture conditions by adding special culture media and using different liver cell lines. These measures resulted in approximately 100 times more infectious virus particles than previously published.

Extensive tests show that the model works

In order to verify whether the new cell culture model can be used to study the virus, the researchers carried out several experiments. For example, they tested whether enveloped and naked viruses are produced in the same way. “Both variants of the virus occur in HEV patients,” explains study author Martina Friesland from the Experimental Virology at Twincore Centre for Experimental and Clinical Infection Research in Hanover. “However, they are responsible for different routes of infection. While the enveloped virus is transmitted by blood-blood contact, such as transfusions, the naked virus is excreted via the stool and causes infection for example through contaminated drinking water.” Both variants can now be studied with the new cell culture model.

In a previous study, the authors had shown that the mutation leads to increased proliferation in all hepatitis E viruses, and that this is also the case in various liver cell lines used in the research. In the current study, they optimised the model once again. “To this end, we have used insights gained in the clinic to improve a preclinical in-vitro model,” elaborates Daniel Todt. The effect of increased proliferation is also evident in healthy human liver cells, as well as in the animal model. Here, virus particles could be detected in the blood and faeces of rodents for more than a month. “In previous models, detection was only ever possible in faeces, because the number of virus particles produced was too low,” points out Daniel Todt. “Now, we can produce infectious viruses in almost unlimited quantities for research purposes and do not have to resort to virus isolates from patients.”

Full grasp of details

Since this was the first time that they were able to infect cells isolated from healthy liver tissue reproducibly with cell culture-derived HEV, the researchers performed deep sequencing: they analysed the entire genetic information of the virus at different points in time of infection, both under and without the influence of drugs. Moreover, they studied the altered expression of different proteins of affected liver cells in response to the infection, both under the influence of drugs and without the influence of drugs. “We wanted to know how the cell reacts to the infection,” says Daniel Todt. “Our aim was to gain a full understanding of the details,” points out Eike Steinmann. “This is the only way to identify genes that are particularly important for the course of the infection and take them under consideration as possible targets for therapeutic approaches in future.” The researchers are making the data set and the optimised protocol available to the public, in order to enable the entire scientific community to conduct follow-up research using the model and the previous findings.