The danger behind certain biologics

The surprising role of an immune cell that explains some of the drugs' side effects

Autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and Crohn's disease plague tens of millions of Americans and are the result of the body's immune system, whose role is to fight against disease-causing pathogens, turning against itself.

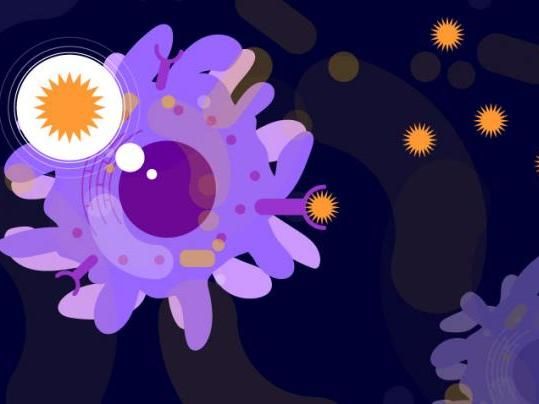

Dendritic cells have their own form of program memory that hinges on a well-known immune signaling molecule called TNFalpha.

Stephanie King

Thankfully, several new drugs designed to fight these diseases are now available. The downside--the drugs, a class of biologics called TNF inhibitors, carry a risk of serious infections and even cancer.

A research team led by Michigan Medicine may have discovered why. Their study, which appears in the journal Science Advances, reveals a previously unknown function of a specific type of immune cell called dendritic cells.

"Dendritic cells are the master orchestrator of the immune response, telling the other cells of the immune system what to do," explains Michal Olszewski, DVM, Ph.D., a research biologist with the Ann Arbor VA Hospital, associate professor of internal medicine at U-M and senior author on the paper.

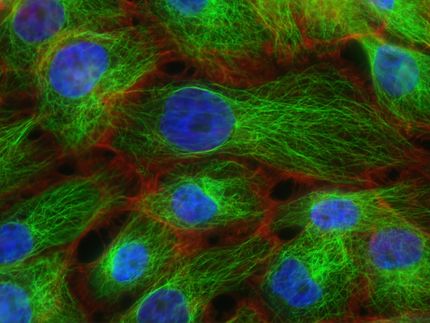

Dendritic cells are part of the innate immune network, the body's first line of defense against a threat. They help another type of immune cell called T cells, which are part of the adaptive immune system, learn how to respond appropriately to a given germ or disease-causing agent.

This study reveals that the cells have their own form of program memory and hinges on a well-known immune signaling molecule called TNFalpha, which causes the inflammation so painfully familiar to those with arthritis and other autoimmune diseases.

"Our studies have found that TNFalpha is part of the system that programs dendritic cells so that they know how to program T cells," says Olszewski.

TNFalpha is especially important in helping dendritic cells teach T cells to fight off infections like certain fungal infections and tuberculosis that can hide inside the body's cells. This is why people taking these autoimmune drugs are particularly at risk.

"Some microbes are very clever and fool the immune system so it doesn't detect and kill them, causing disease. But in our study, we found in the presence of TNFalpha, microbes can't do those tricks. With its help, dendritic cells don't get fooled and therefore can activate the protective T cell response," says co-first author Jintao Xu, Ph.D. of the Ann Arbor VA Hospital.

Furthermore, the group found that the dendritic cell programming relied on rapidly developing epigenetic changes affording dendritic cell program stability and conferred to the T cells. This finding has major implications for the development of therapies targeting the immune system.

"This will be important for vaccine development, for understanding how the immune system responds to chronic infections, and why people who take anti-TNF for treatment of autoimmune diseases are particularly vulnerable to these kinds of diseases," comments Olszewski.

In an additional proof-of-concept study, the team found that by removing dendritic cells from mice taking an anti-TNF drug, exposing the cells to TNFalpha and reinjecting them into the mice, they could induce a normal immune response against infection.

This procedure hints at a complimentary therapy for people on anti-TNF drugs as well as a potential advanced immunotherapy for cancer. "Cancer can produce a group of signals that dampen the immune response. We speculate that one could program the dendritic cells outside of the cancerous environment and make them remember that they are to remain activated and continue to fight the cancer instead of ignoring it," says Olszewski.