Measles infections erase immunological memory

measles infections are not harmless - they can cause disease courses that may be of fatal outcome. Researchers of the Paul-Ehrlich-Institut (PEI) in co-operation with researchers from the UK and the Netherlands have now found out that measles viruses erase part of the immunological memory over several years. Affected persons are thus more susceptible to infections with other pathogens beyond the period of the measles infection.

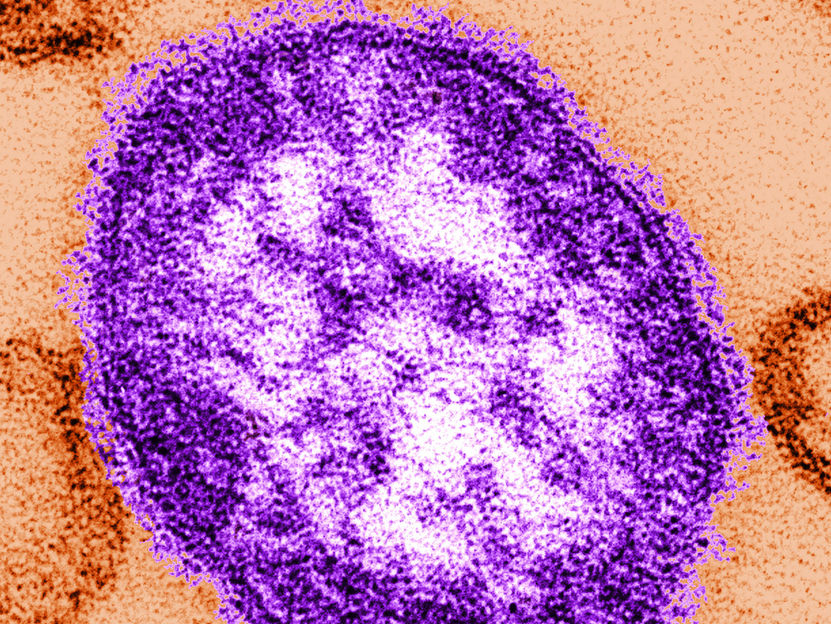

Measles virus

C. Goldsmith, W. Bellini / CDC

Measles should have been eradicated a long time ago, but they are increasing again. In the first six months of 2019, almost three times more cases were reported than in the same period of the previous year. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) has spoken of a measles revival in the European Union and the European Economic Area (EEA). Five countries, including Germany, where transmissions are still endemic (i.e. transmission occurs within the population), are largely responsible for this resurgence.

It has long been known that measles infections themselves can not only cause serious or even fatal disease but, in addition, weaken the immune system of the affected person against other pathogens. Thus, a measles infection can also frequently entail additional infections such as bacterially-associated lung or middle ear infections.

A measles cohort study conducted in the United Kingdom revealed that ten to 15 percent of the children still showed signs of marked impairments of their immune system even five years after a measles infection, leading to an increased occurrence of secondary (further) infections.

The research team of Professor Veronika von Messling, who until September 2018 was head of the Division of Veterinary Medicine at the Paul-Ehrlich-Institut (PEI), Federal Institute for Vaccines and Biomedicines, as part of the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF) and with funding from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), and in co-operation with researchers from the UK and the Netherlands, studied the mechanisms leading to this immune suppression. For this purpose, they studied the variety of receptors of the immune cells and the development of an important group of immune cells for the immune memory, the B memory cells, both in unvaccinated persons with and without prior measles infections and in persons vaccinated against measles. While the genetic composition and variety of the B memory cells was stable in persons without a measles infection and in vaccinated persons, there was a significant increase in the mutation frequency of these cells and an altered isotype (variation) profile in those who had suffered from a measles infection. In around ten percent of the individuals in the study who had been infected by measles, the variety of immune cells was impaired, sometime severely. In addition, the cells were affected by a shift towards immunologically immature B cells, which points to an impaired B-cell maturation process in the bone marrow.

The results showed that after a measles infection the immune system practically forgets with which pathogens it was previously in contact. This leads to immune amnesia. Researchers at the PEI confirmed these findings in the animal model (ferret). The animals were first immunised against influenza, and some of the animals were infected with a mutated canine distemper virus (CDV), which is related to the measles virus. The CDV-infected animals lost most antibodies against influenza and had a more serious disease course than those not previously infected with CDV, when they were infected with the influenza virus at a later date.

"The measles vaccination is not only important for the protection against measles virus but also confers protection from the occurrence or serious courses of other infectious diseases. It also protects the immunological memory which can become severely impaired in the event of measles infections," emphasized Professor Klaus Cichutek, president of the Paul-Ehrlich-Institut.

Original publication

Petrova VN, Sawatsky B, Han AX, Laksono BM, Walz L, Parker E, Pieper K, Anderson CA, de Vries RD, Lanzavecchia A, Kellam P, von Messling V, de Swart RL, Russel CA (2019); "Incomplete genetic reconstitution of B cell pools contributes to prolonged immune suppression after measles"; Sci Immunol Nov 1 [Epub ahead of print].