Epilepsy: Function of "brake cells" disrupted

Advertisement

In some forms of epilepsy, the function of certain "brake cells" in the brain is presumed to be disrupted. This may be one of the reasons why the electrical malfunction is able to spread from the point of origin across large parts of the brain. A current study by the University of Bonn, in which researchers from Lisbon were also involved, points in this direction.

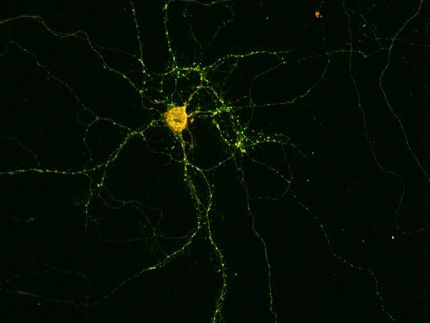

An interneuron (bright, with long appendages) from the hippocampus of a rat. The finely branched axon (top left cloud) surrounds the cell bodies of pyramidal cells and can inhibit these effectively.

© Leonie Pothmann/Uni Bonn

For their study, the researchers investigated rats suffering from temporal lobe epilepsy. This is the most common form of the disease in humans. Unfortunately, it barely responds to the currently available medicines. "This makes it all the more important to determine exactly how it arises," stresses Dr. Leonie Pothmann, who completed her doctorate on the subject at the Institute of Experimental Epileptology at the University of Bonn.

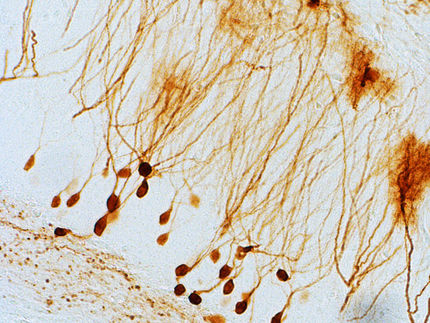

The data that has just been published may help scientists with this endeavor, because they indicate that a certain cell type does not function properly in patients. The affected cells are a class of so-called inhibitory interneurons, which are cells that can attenuate the excitation of brain areas. "We investigated interneurons in the hippocampus, an area of the temporal lobe known as the focus of epileptic seizures," explains Pothmann.

Pyramidal cells play an important role in the transmission of excitation in the hippocampus. They generate voltage pulses in response to an electrical stimulus. These stimulate, among other things, interneurons, which in turn inhibit the pyramidal cells. This feedback loop acts as a kind of brake: It prevents the voltage pulses from propagating unhindered. An epileptic seizure would thus be nipped in the bud before it is able to spread to other parts of the brain.

Brake simulation in the computer

"In the rats, however, this brake did not work well compared to healthy animals," says Pothmann's colleague Dr. Oliver Braganza. "Our measurements show that the rapid, robust inhibition that occurs in healthy animals is greatly reduced in sick animals.”

In order to find out why this might happen and what the effects might be, the scientists simulated the interaction of pyramidal cell and interneuron on the computer. They changed certain properties of the virtual interneuron until its behavior in the simulation was exactly the same as in the sick animals.

The results provide information about two possible disturbances: The interneurons appear to release only a small part of the signal molecules (neurotransmitters) stored inside their cells in response to a stimulus. Additionally, their membranes are not working properly: They are unable to maintain a voltage gradient very well, almost as if they had a slight short circuit. Both factors contribute to the interneurons being activated only relatively weakly. In computer simulation, this interaction with the pyramidal cells resulted in the unhindered transmission of the type of activity that occurs in epileptic seizures.

"We now have to investigate these findings further," explains Prof. Dr. Heinz Beck, head of the Institute of Experimental Epileptology and Associate Member of the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases. "First we have to find out whether the two disruptions are actually responsible for the malfunction of the interneurons. If so, this may open the way to new therapeutic approaches in the long term." However, the results are still pure basic research, he emphasizes. "It is by no means clear whether they will benefit patients - and if they do, it will certainly take many more years."