Key enzyme found in plants could guide development of medicines and other products

plants can do many amazing things. Among their talents, they can manufacture compounds that help them repel pests, attract pollinators, cure infections and protect themselves from excess temperatures, drought and other hazards in the environment.

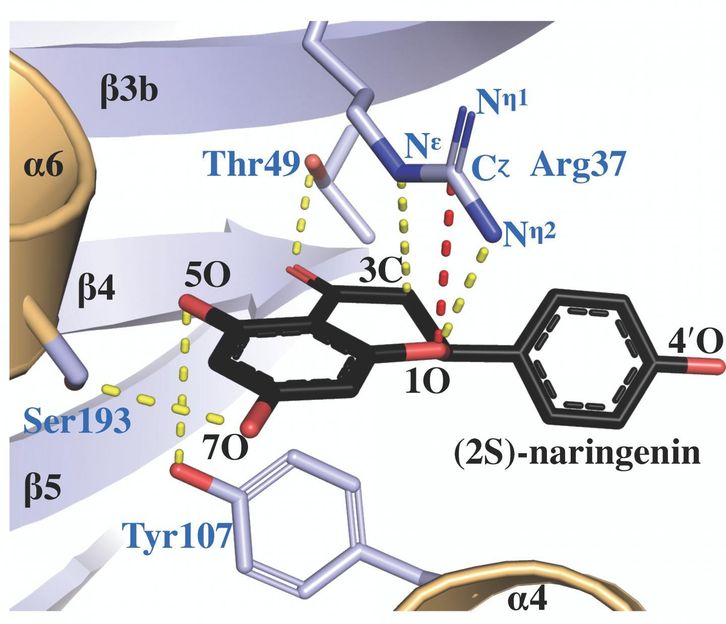

The protein X-ray crystal structure of chalcone isomerase, complexed with a product molecule called (2S)-naringenin, reveals how the active site arginine (labeled as Arg 37) facilitates catalysis of the correct isomer.

Salk Institute/ACS Catalysis

Researchers from the Salk Institute studying how plants evolved the abilities to make these natural chemicals have uncovered how an enzyme called chalcone isomerase evolved to enable plants to make products vital to their own survival. The researchers' hope is that this knowledge will inform the manufacture of products that are beneficial to humans, including medications and improved crops.

"Since land plants first appeared on earth approximately 450 million years ago, they have developed a sophisticated metabolic system to transform carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into a myriad of natural chemicals in their roots, shoots and seeds," says Salk Professor Joseph Noel, the paper's senior author. "This is the culmination of work we've been doing in my lab for the past 20 years, trying to understand plant chemical evolution. It gives us detailed knowledge about how plants have developed this unique ability to make some very unusual but important molecules."

Previous research in the Noel lab looked at how these enzymes evolved from non-enzyme proteins, including studying more primitive versions of them that appear in organisms such as bacteria and fungi.

As an enzyme, chalcone isomerase acts as a catalyst to accelerate chemical reactions in plants. It also helps to ensure the chemicals that are made in the plant are the proper form, since molecules with the same chemical formula can take two different variations that are mirror images of each other (called isomers).

"In the pharmaceutical industry, it's important that the drugs being made are the correct version, or isomer, because using the wrong one can lead to unintended side effects," says Noel, who is director of Salk's Jack H. Skirball Center for Chemical Biology and Proteomics and holds the Arthur and Julie Woodrow Chair. "By studying how chalcone isomerase works, we can learn more about how to accelerate the manufacture of the correct isomers of pharmaceuticals and other products that may be important to human health."

In the current study, the investigators used several structural biology techniques to investigate the enzyme's unique shape and how its shape changes as it interacts with other molecules. They pinpointed the part of chalcone isomerase's structure that allowed it to catalyze reactions incredibly fast while also ensuring it makes the proper, biologically active isomer. These reactions lead to a host of activities in plants, including converting primary metabolites like phenylalanine and tyrosine into vital specialized molecules called flavonoids.

It turned out that one particular amino acid, arginine, that was one of many amino acids linked together in chalcone isomerase sat in a location, shaped by evolution, that allowed it to play the key role in how chalcone isomerase reactions were catalyzed.

"By doing structural studies and computer modeling, we could see the very precise positions of arginine within the enzyme's active site as the reaction proceeded," says first author Jason Burke, a former postdoctoral research in Noel's lab who is now an assistant professor at California State University San Bernardino. "Without that arginine, it doesn't work the same way."

Burke adds that this type of catalyst has been long sought by organic chemists. "This is an example of nature already solving a problem that chemists have been looking at for a long time," he adds.

"By understanding chalcone isomerase, we can create a new toolset that chemists will be able to use for the reactions they're studying," Noel says. "It's absolutely vital to have this kind of foundational knowledge to be able to design molecular systems that can carry out a particular task even in the next generation of nutritionally dense crops capable of transforming the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide into molecules essential for life."