Preventing tumour metastasis

When cancer cells spread in the body, secondary tumours, called metastases, can develop. These are responsible for around 90 percent of deaths in cancer patients. An important pathway for spreading the cancer cells is through the lymphatic system, which, like the system of blood vessels, runs through the entire body and connects lymph nodes to each other. In the migration of white blood cells through this system, for example to coordinate the defense against pathogens, one special membrane protein, the chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7) plays an important role. It sits in the shell of the cells, the cell membrane, in such a way that it can receive external signals and relay them to the interior. Within the framework of a joint project with the pharmaceutical company F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG (Roche), researchers at the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) have for the first time been able to decipher the structure of CCR7 and lay the foundation for the development of a drug that could prevent metastasis in certain prevalent cancer types, such as colorectal cancer.

Steffen Brünle (right) and Jörg Standfuss at the apparatus they use to separate proteins from each other. For their study, the researchers modified insect cells to produce a human protein. To extract this from the cell, the cell was destroyed, and then the protein, whose structure the researchers have now elucidated, was separated with the help of this apparatus.

Paul Scherrer Institut/Markus Fischer

In the cells of all vertebrates, there are 20 different chemokine receptors that can interact with more than 40 signaling proteins called chemokines. Each of these signaling proteins fits only to very specific receptors. In turn, if one of the signaling proteins binds to a receptor, it triggers processes inside the cell that lead to a specific cellular response to the signal.

CCR7 is one of the receptors that control the movement of cells within the body. As soon as the appropriate signaling protein outside the cell binds to it, a chain reaction in the cell causes the cell to move in the direction of the highest concentration of the signaling protein. The cell follows the track of the chemokine like a hound following a scent. For example, a constant flow of white blood cells, important cells of the body's immune system, is directed to the lymph nodes.

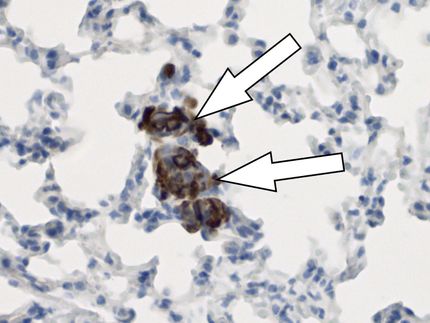

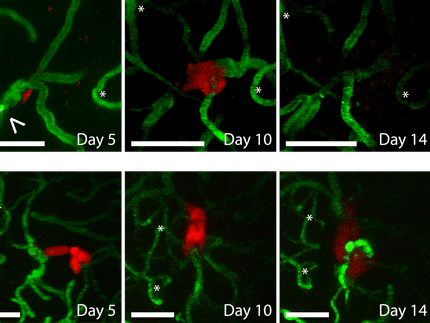

Cancer cells too can take advantage of CCR7 and misuse the cell receptor for their own purposes. The appropriate signaling protein guides them out of the tumour and into the lymphatic system. Furthermore, they spread in the body and eventually form metastases in other tissues. These daughter tumours drastically increase the mortality risk for those affected.

Artificial agents prevent cells from migrating

To increase the survival rate of cancer patients, it is of great medical interest to suppress the metastasis process. That is why PSI researchers have used X-ray crystallography at the Swiss Light Source (SLS) at PSI to decipher the structure of the CCR7 receptor.

This structure served as the basis of the search, in collaboration with Roche, for corresponding active agents. "The right molecule can prevent the signaling protein from coupling to the receptor and causing a reaction in the cell", explains Steffen Brünle, who conducted the study as a postdoctoral researcher in the PSI-FELLOW-II-3i programme and is one of the first authors of the paper. Deciphering the structure of the receptor was a real challenge. "The difficult thing about it was producing them, in the first place, in such a way that we could examine them with X-ray crystallography", says Jörg Standfuss, co-leader of the project and the Time-Resolved Crystallography research group at PSI. In order to speed up the research process, Roche developed its own new protein-modifying technology modules, so-called crystallisation chaperones.

With information about the precise structure of the receptor, they were able to identify a suitable molecule that blocks the receptor and thus prevents a signal from being transmitted into the cell. "Our experiments show that the artificial molecule, inside the cell, binds to the receptor. This keeps the chain reaction that leads to cell migration from getting started", Brünle says.

The value of scientific collaboration

From millions of molecules deposited in a database at Roche, and using the structure of the drug-bound receptor, Roche scientists used computer simulation to search for fitting agents that could be suitable for blocking the signaling protein, and they identified five compounds as possible candidates for further development of potential cancer therapy drugs.

Also, one of the active agents the researchers discovered in their study is already being tested by the pharmaceutical industry, in clinical trials, as a potential drug against metastasis. Previously it had been thought that this agent binds to a different receptor and thus inhibits another function of the cancer cell. This highlights how insights from such studies can be extraordinarily valuable for pharmaceutical research and development.

Original publication

"Structural basis for allosteric ligand recognition in the human CC chemokine receptor 7"; K. Jaeger, S. Bruenle, T. Weinert, W. Guba, J. Muehle1, T. Miyazaki, M. Weber, A. Furrer, N. Haenggi, T. Tetaz, C. Huang, D. Mattle, J.-M. Vonach, A. Gast, A. Kuglstatter, M.G. Rudolph, P. Nogly, J. Benz, R.J.P. Dawson, J. Standfuss; Cell; 22. August 2019 (online)