Mental Fitness Improved by Multilingualism?

Advertisement

Learning a second language increases your brain volume. This effect is particularly clear at the beginning of the learning process. As part of the 1000BRAINS study, scientists from Jülich, Düsseldorf, and Aachen investigated how the relevant brain regions change during the course of aging. The results were published in the journal Neurobiology of Aging and may explain why multilinguals often stay mentally fit for longer.

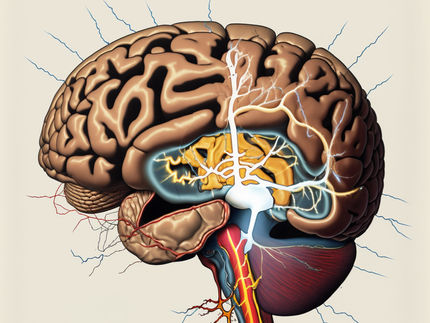

The study comprised 224 people who speak only one language and 175 people who speak two languages fluently. “We focused on two specific regions in the left cerebral hemisphere that are known for their role in language processing, among other functions,” explains Prof. Dr. Stefan Heim, head of the Neuroanatomy of Language working group at Jülich’s Institute of Neuroscience and Medicine and professor at University Hospital Aachen’s Department of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics.

The interdisciplinary team of medical scientists, psychologists, linguists, and speech therapists used magnetic resonance imaging to investigate how pronounced the volume of grey matter is in the left inferior frontal gyrus and in the inferior parietal lobule cortex. “These two brain regions are important for tasks such as language comprehension and production,” explains Heim, who also heads RWTH Aachen University’s Logopedic Courses of Study. “Certain parts of these regions frequently work together, which means that they are functionally and anatomically closely linked in all humans,” adds Heim.

The researchers have now shown that the grey matter in the two regions initially has a much greater volume when a person learns a second language at a young age. Grey matter is rich in nerve cell bodies. The scientists think that the volume increase in this layer is due to a stronger interconnection between neighbouring nerve cells. The study shows that with advancing age, the volume of grey matter in the two brain regions decreases in both monolinguals and multilinguals. The volume of the language region in the frontal lobe of multilinguals remains somewhat greater than that of monolinguals up to the age of around 60. Only then do the two groups level out and no longer show volume differences. The area in the parietal lobe remains stable even longer, according to the researchers’ findings. Only at 80 years did the researchers no longer find a volume difference between the grey matter in the parietal lobes of multilinguals and monolinguals.

“In our experience, an increase in grey matter is associated with an increase in cognitive reserve – which means improved mental performance and flexibility,” says Heim. “At first glance, these findings appear to show that the advantage of learning a second language are particularly pronounced at a young age but that this levels out with increasing age,” he explains. “But we know from the work of other research groups that this advantage does not, in fact, simply vanish. The surplus grey matter transforms over time – as knowledge of a language becomes firmer – into a tighter interconnection of the areas and more pronounced communication pathways in the white matter,” Heim adds. “This makes the information exchange between the brain regions easier and therefore more stable and effective,” he says. This could explain why multilinguals are often mentally fitter at higher ages.

Prof. Dr. Dr. Svenja Caspers, head of Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf’s Institute of Anatomy I and head of the Connectivity working group and the 1000BRAINS study at Jülich’s Institute of Neuroscience and Medicine, says: “Now that we know how the structure of the grey matter in the two language regions changes in multilinguals and monolinguals, we want to conduct a follow-up study to find out what the functional ‘wiring’ – or the connectivity – of the two language regions looks like in multilinguals and monolinguals at advanced ages,” she says. “We are interested in how exactly they interact and how this changes throughout life,” Caspers adds. “Another fascinating question is whether learning a second or third language at an advanced age is advantageous for mental performance,” she says. “This would represent a practicable and simple method for many people to increase their cognitive reserve,” she stresses.