Speed controllers for protein production

Advertisement

The translation of the genetic code into proteins is a vital process in any cell. Prof. Mihaela Zavolan’s team at the Biozentrum, University of Basel, has now uncovered important factors that influence the speed of protein synthesis in the cell. The results, recently published in “PNAS”, serve as a basis to better analyze translational control in a wide range of cell types.

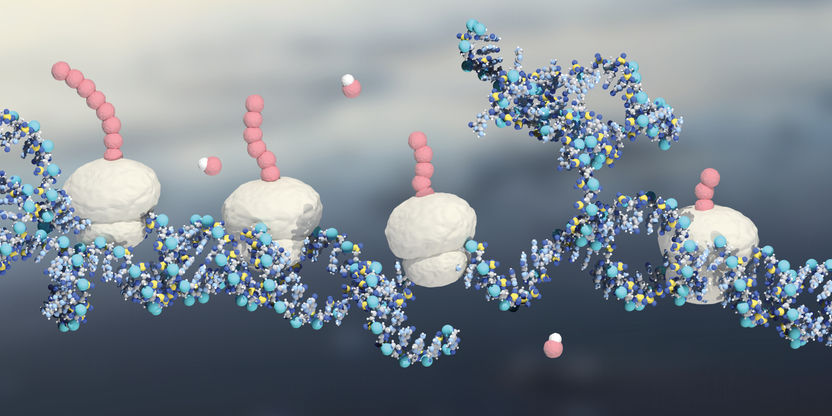

Model of the protein synthesis in the cell: The ribosomes (white) translate the mRNA (blue) into proteins (pink).

University of Basel, Biozentrum

Proteins perform various jobs in cells, they catalyze thousands of biochemical reactions, relay signals and are required for building cellular structures and transport processes. Within every single cell of our body vast quantities of proteins are produced non-stop.

The growth, differentiation and functions of cells are intimately coupled to their protein synthesis activity, which translates the genetic code into proteins. The research team led by Prof. Mihaela Zavolan at the Biozentrum, University of Basel, has investigated thousands of genes in growing yeast cells and uncovered determinants affecting the speed with which different proteins are synthesized.

Protein synthesis: From genetic code to protein

The production of proteins requires three main players: the mRNA that carries the gene’s message and works as a template; the tRNA brings the protein building blocks, the amino acids, to the ribosome; and the ribosome that chains the amino acids into the protein sequence. In a typical eukaryotic cell, there are millions of ribosomes that assemble proteins, according to the specific needs of the cell. Lined up like string of pearls, multiple ribosomes are typically working on a given mRNA to simultaneously produce a corresponding number of proteins.

Factors that control protein translation

“We wanted to know which factors determine the synthesis rates of proteins, especially at the level of the elongation of the amino acid chain. Earlier studies suggested it is infrequently that ribosomes collide with each other, which would reduce the protein output,” says Zavolan, “but we couldn’t find evidence supporting this crash, even for mRNAs with high ribosome density.”

Furthermore, the researchers have discovered that also the charge of the incorporated amino acids is as important for the speed of elongation as the availability of tRNAs. “This is, for example, the case for the proteins of the ribosome itself. We found that the positively charged amino acids of ribosomal proteins markedly reduce the speed with which ribosomes proceed on the corresponding mRNAs,” says Zavolan. “However, ribosomal proteins are optimized in many ways to keep a high speed of translation, for example by being encoded with codons that correspond to very abundant tRNAs.” In addition to the well-known parameters, the factors described in the study play quite a substantial role in explaining the variability in translation rates between mRNAs.

From sensitive mRNAs to disease

The scientists want to further investigate how translational control contributes to the regulation of cell fate. There are indications that certain mRNAs are more sensitive to changes in the number of ribosomes in the cell than others. One such mRNA encodes a transcription factor involved in the formation of red blood cells. “A reduction in the number of ribosomes, caused by mutations, strongly affects this factor and impairs the maturation process of red blood cells. Therefore, the affected individuals suffer from anemia”, says Zavolan. “By extending our approach to other systems, we aim to better understand which mRNAs are especially sensitive to changes in translation.”