Honouring a pioneer of DNA testing

Margarita Salas named European Inventor Award 2019 finalist

Advertisement

The European Patent Office (EPO) announces that Spanish scientist and university professor Margarita Salas Falgueras has been nominated for the European Inventor Award 2019 for her pioneering invention that enables DNA tests to reconstruct full genomes from small samples such as a single hair follicle or trace of blood. Her invention has grown into a pillar of modern genetics and has applications in a broad range of fields.

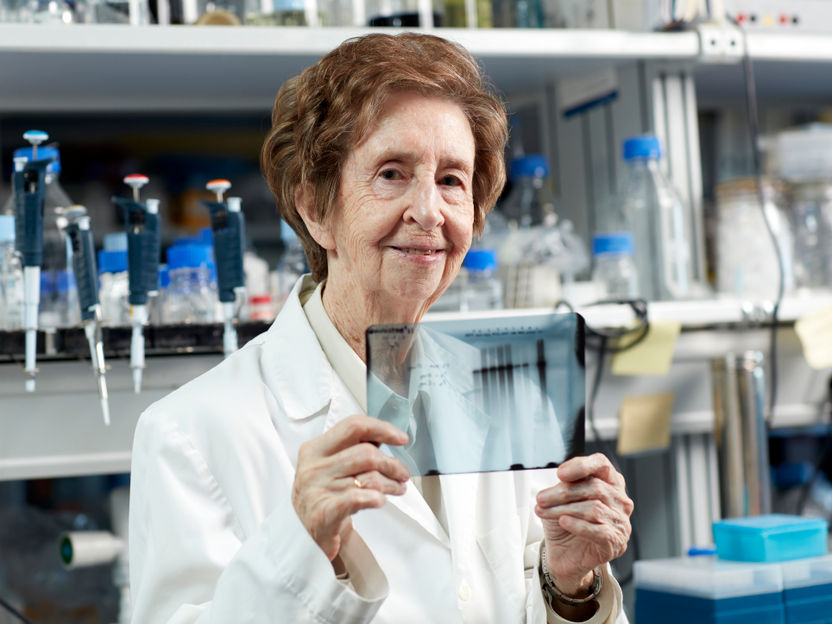

Margarita Salas Falgueras (Spain), nominated for the European Inventor Award 2019 in the category Lifetime achievement

European Patent Office

Named as one of three finalists in the prestigious "Lifetime achievement" category, Salas - who is now Honorary Professor at the Centre for Molecular Biology Severo Ochoa at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) in Madrid - developed a technique that amplifies the smallest samples of DNA into quantities large enough for full genomic analysis, by copying single DNA molecules into millions of identical replicas. It is widely used in genetics laboratories around the world.

"Over her lifetime, Margarita Salas has turned DNA testing from a niche experiment into a unique everyday work tool in sectors ranging from medical research and oncology to archaeology and forensics," said EPO President António Campinos announcing the European Inventor Award 2019 finalists. "Her invention has put DNA sequencing within reach of many more researchers and scientists, paving the way for further breakthroughs in genetics. Her patents were commercialised to great effect, making it possible to fund even more research."

The winners of the 2019 edition of the EPO's annual innovation prize will be announced at a ceremony in Vienna on 20 June.

Unlocking vast potential with a tiny virus

Salas's initial invention owes much to the challenging conditions under which she worked. After receiving her PhD in biochemistry in 1963 from the Complutense University of Madrid, she spent three years working with Nobel Prize winning biochemist Severo Ochoa at New York University. She then returned to her native Spain, where funding for scientific research was limited.

With CSIC support and a grant from the Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund for Medical Research from the US, Salas founded the country's first research group on molecular genetics in 1967 at the CSIC in Madrid. Mindful of the costs, she focused her research on a comparatively simple, yet understudied, bacterial virus called phi29 - a choice that would define her career and pave the way for modern genetics and forensics.

By 1982, genetics had grown into a vibrant field of research, but copying genomes remained challenging. Emerging techniques such as the polymerase chain reaction, a molecular biology method to make copies of specific DNA segments, were slow and introduced at least one error in each 9 000 base pairs of DNA. Salas discovered that phi29 could create an enzyme, called phi29 DNA polymerase, that assembled DNA molecules much faster than alternatives and much more accurately - with fewer than one error in a million base pairs.

Salas isolated the enzyme and demonstrated that it also worked in human cells, unlocking ground-breaking applications for DNA testing. For the first time, this high accuracy replication made it possible to obtain reliable results from small quantities of genetic material. The technique is used today in medical research to study microbes that cannot be cultured in the laboratory. It has shed light on the earliest stages of embryonic development and allows oncologists to zoom in on small sub-populations of cells that could give rise to tumours. It also supports forensic specialists and archaeologists as trace amounts of DNA collected from crime scenes and historical sites can now be amplified by phi29 DNA polymerase to identify victims, suspects and even fossils.

"Basic research can give rise to applications that could never have been foreseen and that can truly benefit society," says Salas.

The potential of Salas's invention was soon acknowledged by the United States Biochemical Corporation (USB) who in the late 1980s approached CSIC asking them to apply for a patent so that they could commercialise it, in the form of user-friendly DNA sequencing kits. Salas and CSIC filed the initial US patent application to protect phi29 DNA polymerase and its uses in 1989, and the patent was granted in 1991. USB originally licensed the patent from CSIC and sub-licensed it to Amersham Biosciences (later acquired by General Electric Healthcare). The European patent was granted in 1997.

Driving molecular genetics forward

Salas's patent became the most profitable patent ever filed by CSIC, generating royalties of over EUR 6 million between 2003 and 2009. The earliest European patent for phi29 DNA polymerase expired in 2009, resulting in other companies competing on the market for DNA amplification. The market for products incorporating generic phi29 DNA polymerase grew to an estimated EUR 50 million by 2012 - and is expected to reach EUR 156 million by 2020.

The patent for her method using phi29 DNA polymerase was key in enabling Salas and her team to make further advances in her research, as CSIC royalties continued to fund her lab'’s activities. This was especially important given the limited public funding available.

Today at the age of 80, Margarita Salas continues to go to the laboratory every day. Her later patents and her ongoing research are extending the capabilities of phi29 DNA polymerase, notably building on mutations of the virus with properties such as higher amplification efficiency and heat-resistance to amplify DNA under broader experimental conditions.

Salas uses her public visibility to promote basic research and greater participation of women in science. She was the first female professor in her department and the first woman to preside over the Instituto de España, the institution regrouping Spain's eight royal academies. "When I started my PhD in 1961 there were almost no women doing research in Spain," she says. "Nowadays there are more women than men starting a PhD in our laboratories."

Throughout her career she remained dedicated to education, having taught molecular biology to students at the Complutense University of Madrid for 24 years, during which she supervised over 35 PhD dissertations. She has won numerous awards for her work, is a member of Spanish, European and US science academies, and has several streets named after her in different cities in Spain.

Having brought molecular genetics to her home country and a revolution to the DNA amplification industry, the Spanish researcher sees no reason to stop doing what she loves most: science.