A peptide against cannibalism

A small molecule safeguards roundworm larvae against parental attacks

Advertisement

A worm whose favorite dish is – of all things - worm larvae has to take great care not to accidentally devour its own progeny. How these tiny worms of merely a millimeter in length manage to distinguish their own offspring from that of other worms and avoid cannibalism has recently been discovered by scientists of the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in Tübingen. They found that Pristionchus recognizes its offspring by means of a complex mechanism. The worms carry a small, highly variable protein on their surfaces, which seems to be detected by the worm nose. The variable part of the protein likely functions as a self-recognition code and the change of even one amino acid leads to cannibalism.

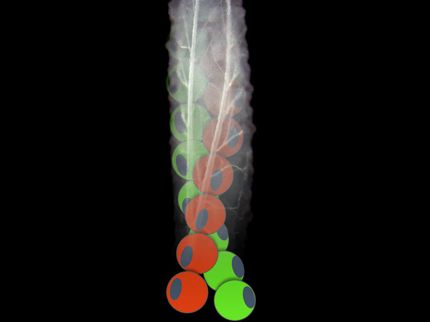

The nematode Pristionchus is a predator. Here it is killing a Caenorhabditis larvae. A peptide on the body surface of its larvae keeps the worm from devouring its own offspring.

© MPI f. Developmental Biology/ J. Berger, R. Sommer

”Self-recognition is found all over the animal and plant kingdoms”, says Ralf Sommer, leading scientist of the Max Planck group in Tübingen, who has established Pristionchus as a model organism for comparative studies with the well-known nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. “This includes being at the heart of biological processes ranging from the aggregation of single-celled organisms to social or aggressive behaviors in various animals and is also a key part of the human immune system responsible for warding off pathogens. But despite the prevalence of self-recognition in general, this kind of organismic self-recognition has not been described in nematodes before”, says Sommer.

To investigate how finely the worms can distinguish between self and non-self-progeny, the researchers carried out a series of experiments to asses prey preferences. In multiple separate experiments, adult worms of different Pristionchus species were offered their own larvae, C. elegans larvae, larvae of a different Pristionchus species, or larvae of a related line within their own species as prey.

Signals on the body surface

In all of the experiments, worms avoided attacking larvae of their own line; but they did not hesitate to feed on C. elegans larvae, progeny of closely-related species, or even offspring of lines within their own species. Even predators that were put into a mixed culture with their own larvae and those of a different Pristionchus species exclusively selected the “non-self” offspring as prey. “This finding rules out that their own larvae are recognized by pheromone-like substances that are emitted into the environment as self-recognition remains intact in the mixed culture”, explains James Lightfoot, first author of the study. The observation that feeding adult animals always first make nose contact before they bite is further proof that the decisive signals are located on the body surface.

By means of targeted mutations, Sommer and his team were able to identify a gene, which plays an essential role in distinguishing “self” from “non-self” and was aptly named self-1 by the scientists. self-1 codes for a small protein of 63 amino acids – the building blocks of proteins. Large parts of the protein are highly conserved, which means that they possess the same amino acid sequence even in distantly related species.

Variable molecule region

A small region at the end of the protein, however, is highly variable – with clear differences even between closely related lines of P. pacificus. In mutation experiments the exchange of a single amino acid in this region proved to be sufficient to prevent self-recognition and disable the protection against cannibalistic attacks. “Thus SELF-1 seems to represent a self-recognition code and is maintained on the surface of the worm throughout its entire lifespan”, explains Sommer.

Further experiments, however, have shown that the possession of a species-specific SELF-1 protein is not the only signal on which the decision of whether or not to attack depends. C. elegans larvae were also attacked by P. pacificus after they had been equipped with the P. pacificus SELF-1 protein by genetic engineering. “Obviously, SELF-1 is part of a more complex mechanism, which regulates the distinction of “self” and “non-self””, says Sommer. “P. pacificus therefore provides an ideal model system to study the mechanism behind self-recognition together with its evolution and the strategies this worm uses in competitive situations.”

Original publication

James W. Lightfoot, Martin Wilecki, Christian Rödelsperger, Eduardo Moreno, Vladislav Susoy, Hanh Witte, Ralf J. Sommer; "Small peptide–mediated self-recognition prevents cannibalism in predatory nematodes"; Science; 5 April, 2019