Traffic Jam in the Cell: How Are Proteins Assigned to Specific Transporters?

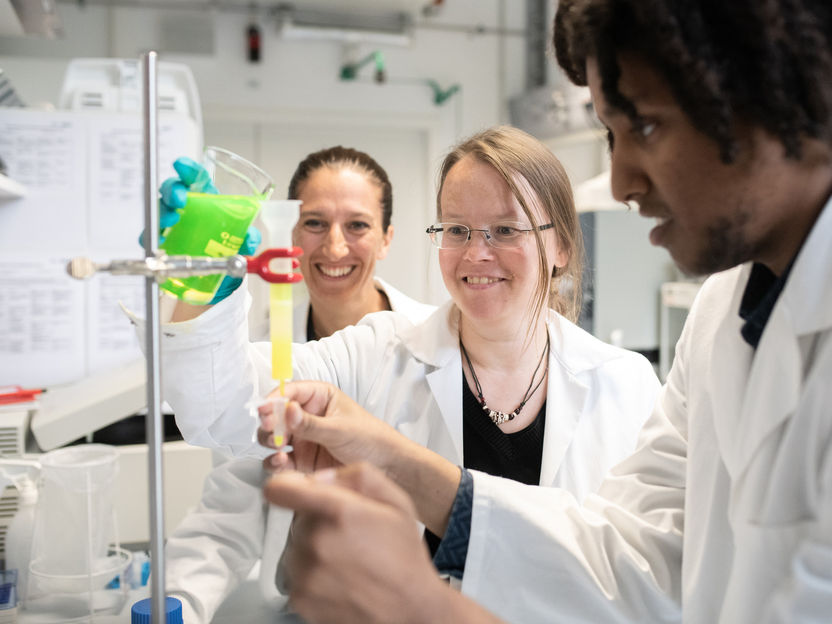

Researchers comprehensively identify the composition of transport vesicles for the first time

A fundamental cellular mechanism ensures that proteins are transported to the places they are needed in the cells. So-called vesicles are responsible for that transport. Determining their composition has been difficult up to now, not least because of their short life span. By combining innovative investigative techniques, biochemists at Heidelberg University have succeeded in analysing two of these transport vesicles – the COPI and COPII vesicles – comprehensively for the first time.

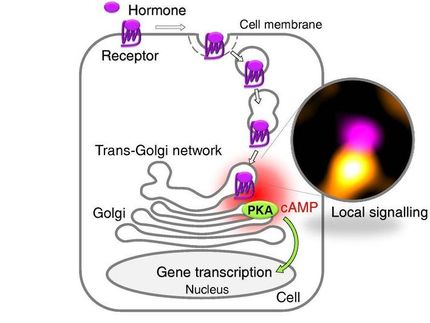

About a third of all the proteins that are made in our cells start their lives in the endoplasmic reticulum, that serves as a general protein factory. However, most proteins are needed at other cellular locations and need to be transported there. To avoid a “traffic jam”, cells have evolved transport vesicles that act as a public transportation system: Passengers – the protein cargo – need to present the correct ticket to board the right bus – a specific type of vesicle – and end up at the correct destination.

Scientists have known for decades that small vesicles that form on the surface of organelles package specific proteins and transport them to other areas of the cell or the cell surface. “Mutations in genes involved in vesicular transport often lead to disease. It is therefore crucial to understand which proteins are transported by which vesicles. Unfortunately transport vesicles have a short life span and are challenging to purify, so they are difficult to analyse,” states Prof. Dr Felix Wieland, who headed up the research at the Heidelberg University Biochemistry Center (BZH).

The researchers combined two approaches to study the composition of the COPI and COPII vesicles in greater detail for the first time. A vesicle reconstitution procedure made it possible to produce and purify large amounts of vesicles. They also used stable isotope labelling with amino acids in cell cultures. This procedure – called SILAC for short – allows precisely quantifying different protein amounts using mass spectrometry.

“Being able to generate specific types of vesicles and to analyse their protein contents allowed us to define a catalogue of protein cargo for COPI and COPII vesicles. One key finding is that subtypes of COPII vesicles seem to have specialised in transporting certain types of proteins,” stresses Dr Frank Adolf, the study‘s primary author. The researchers now hope that this approach will open the way to better understand how mutations that affect vesicular transport can lead to diseases.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

The veins in your brain don't all act the same

NIST calculations may improve temperature measures for microfluidics

Discrete_nanoscale_transport

Intertek Acquires Divisions of Ciba Expert Services from BASF - Expands Services Globally

Helix BioPharma Corp. Completes Enrollment in Its Phase II Trial of Topical Interferon Alpha-2b

List_of_surgeons